How fake is that post? This will help you spot deception after the election

In the lead up to the 2020 election, KUOW’s The Record has focused each week on stories and research exploring the power of misinformation locally, disinformation nationally, and what we can do to detect and combat false information online. Here's what we learned.

But first: What's the difference between misinformation and disinformation?

The biggest difference is intention. Misinformation can include honest mistakes, accidents, posts shared without close reading, and the small decisions everybody makes as they navigate information online.

Virality is especially important when it comes to misinformation, as the ease through which articles, memes, and videos circulate on the internet is often the result of quick button-clicking from millions of users. Misinformation is not seeking to maliciously deceive.

Disinformation, in contrast, harbors an intent to deceive. This can mean a creator or group intends for false stories to circulate online by strategically manipulating emotions and biases, such as political beliefs or social issues a user supports.

This doesn’t have to include blatantly false information, and can include the use of true or half-true information in incorrect contexts. Disinformation includes narratives pushed by conspiracy theorists and includes governments seeking to meddle in elections and movements.

Sponsored

What kinds of misinformation should I be on the lookout for?

Information about crises

Crisis events are critical times for misinformation spread. This is due to the fast moving nature of unverified information as officials investigate the science and research of an event.

When it comes to large disruption events, people look for explanations that validate their insecurities, whether or not that explanation has a trustable source behind it.

In addition to inciting people to commit very real crimes such as violence or kidnapping, these crisis misinformation campaigns cause confusion that disrupts the ability of officials to do their jobs correctly.

Sponsored

We saw this kind of misinformation spread during this year’s wildfires across the West Coast.

When fires engulfed Oregon, anxiety in QAnon and conservative circles online toward protests in Portland bubbled over into the conspiracy theory that antifascists (antifa) were intentionally setting wildfires as part of a coordinated political attack.

The theory gained widespread traction when Republican Paul Romero Jr., a former U.S. Senate candidate in Oregon, retweeted it.

It was picked up through forums and right-wing news circles, whose viewers flooded 911 lines with concerns about antifa.

Journalists also reported an armed militia in Corbett, Oregon, who intercepted drivers in the area to check if they were members of antifa.

Sponsored

Police, FBI, and government officials confirmed the conspiracy was false and urged locals to save emergency calls for those in immediate danger from fire. Even with the help of 15,000 fact checkers at Facebook, the span between the fires’ beginning and official investigations into their cause allowed conspiracy theories to spread and disrupt critical emergency response.

“It’s during crisis events when uncertainty levels are high, anxiety levels are high, but the information we’re looking for is in low supply,” says Jevin West, the Director of the Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington. He and other experts say that in general, officials will provide you with the most trustable account of a crisis as it unfolds - even if that account isn't coming quickly and sometimes is incorrect.

Deepfakes

Deepfakes are videos that use AI-powered technology to invent fake but realistic recreated videos. Because of their realistic appearance, these videos can make public figures appear to say things they never did, spoofing viewers into believing quotes and events that never happened. Cheapfakes are low-quality videos that make slight alterations to existing videos, such as slowing down, speeding up, or adding low quality changes (such as the video of Democratic Presidential Candidate Joe Biden sticking out his tongue last month).

While deepfakes are convincing, many disinformation campaigns opt toward the use of cheapfakes because of their cost and expediency.

Sponsored

Deepfakes took off in 2018 when various groups began using the technology to superimpose women's faces onto bodies in pornography. In the case of many women, the distribution of false and manipulated videos led to harassment, abuse, and the loss of careers and families.

Even when flagged, these videos can evade deletion by circulating through forums and dark corners of the web. Deepfake porn videos (especially of women) make up the majority of deepfake videos online.

“The technologies exist now, for those who want to invest in them, to create deepfakes that are super hard to detect,” says Tom Burt, Microsoft’s vice president of Customer Security and Trust. “In the long run, the deepfake technology will always defeat the detection technology. So we need to do more.”

Who should we trust? Who are we accidentally trusting?

We put trust in a variety of places. Increasingly, whether it’s shopping for beauty products or parenting tips, we’re looking at influencers — everyday content creators we feel a connection to through their lifestyles. That connection, and the resulting power that gives some lifestyle influencers, has led to a misinformation campaign some experts call “Pastel QAnon.”

Sponsored

The appearance and personality behind lifestyle influencer content feels safer and more legitimate than the traditional sources of disinformation, which can originate in corners of online forums and closed conspiracy groups.

As more people curate news and entertainment through YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, they look for personalized connections to influencers who help form their buying and lifestyle decisions; as we’ve seen in the COVID-19 pandemic, these influencers can also spread false information about politics and health through their approachable, stylized appearances.

“If we talk about mommy bloggers, viewers are concerned about their kids. I’m concerned about the health and the wellbeing of my friends, and particularly my family,” says Kolina Koltai, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

When influencers feel a lack of control in their personal lives — like during the Covid-19 pandemic — they seek out explanations that eventually make their way to social platforms.

“It’s not just about the pandemic itself," says Koltai. "It intersects with policy, with other conspiracy theories about who has control of power.”

What sources should we trust?

For decades, the media, schools, and the government have been our traditional centers of trust. We rely on these institutions to provide us with accurate information about the state of the world and how we can live within it.

But as each of these institutions make decisions that sow doubt, and as information becomes more widely accessible and specialized, we find it difficult to believe that any one place online can provide information everyone agrees is true.

“Because of the explosion of online sources, you could really pick and choose which information you deem to be right,” says Rachel Moran, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for an Informed Public studying trust in online information.

“We’ve seen this shift in our assessments that show trust is not necessarily in sources that have proved themselves to be professional, ethical, or transparent – instead, we attach trust to things we like.”

The result of losing trust in our institutions is a lack of confidence in information generally. Whether it’s in our media, our government, or an influencer, we need to place trust in things that help guide our lives.

When we lose trust in one source of information, we place it within something else, and misinformation campaigns are counting on pushing widespread distrust in public officials, experts, and reputable media so they can to push people into more extreme viewpoints, increasing partisanship and attenuating our reliance on centers of truth.

When feeling like we can’t believe any information, we most often replace our trust in the sources that fit our worldviews, decreasing the likelihood we’ll think critically of the information we consume.

So what should I do? How do I combat misinformation, especially during the election?

There’s no panacea for online misinformation. It’s on everyone to reflect on their part in the information ecosystem, as most all of us post, like, and share information online. We’ve learned several tips and tricks for spotting and slowing the spread of online misinformation and disinformation.

- SIFT: Stop. Investigate the source. Find better coverage. Trace claims.

- Be cautious: Pausing, especially, is a useful practice for slowing the spread of misinformation. Read articles past the headlines, verify the URL is a legitimate site, and find sources who are trustworthy. Think more, share less.

- Question your biases: If you find yourself agreeing with a meme, video, or viral story at face value, question if that’s because of existing biases. We’re more likely to spread misinformation that we agree with, or that feels tailored to the things we like.

- Watch out for friend-of-a-friend post: A lot of misinformation spreads because of people we trust through shaky personal networks, which are difficult if not impossible to verify.

- Be wary of first-hand accounts heard through the grapevine, or from strangers who haven’t had their account corroborated.

- Watch out for statistics: Statistics are easy to misrepresent, mischaracterize, and often appear sensational when used out of context. Especially on Election Night, statistics will be used to declare winners, losers, and fraudsters before any result is verified.

- Trust public officials: Officials don’t always have the full information and don’t always get it right, but they will be more trustworthy than a stranger or friend who’s shared a salacious headline. The tools for investigating an event takes time, but those in charge of reporting a crisis will inevitably be one of the most trustworthy.

- Ask if the media you follow is trustworthy: We readily put trust in sources of information, but we rarely question if that source is trustworthy.

- Reflect on the trustworthiness of where you get your information: Who are they speaking to, what are they citing, do they have an agenda?

- Call out misinformation when you see it: While you may not change the mind of someone in a comment thread, each post and reply is part of a public record and may change the mind of someone scrolling through.

- Always ask if what you're seeing makes sense: Deepfakes are frequently targeted at public officials to make them say comments that are out of character.

When seeing a video like this, ask: does this video make sense? Is this something that this official or figure would realistically say?

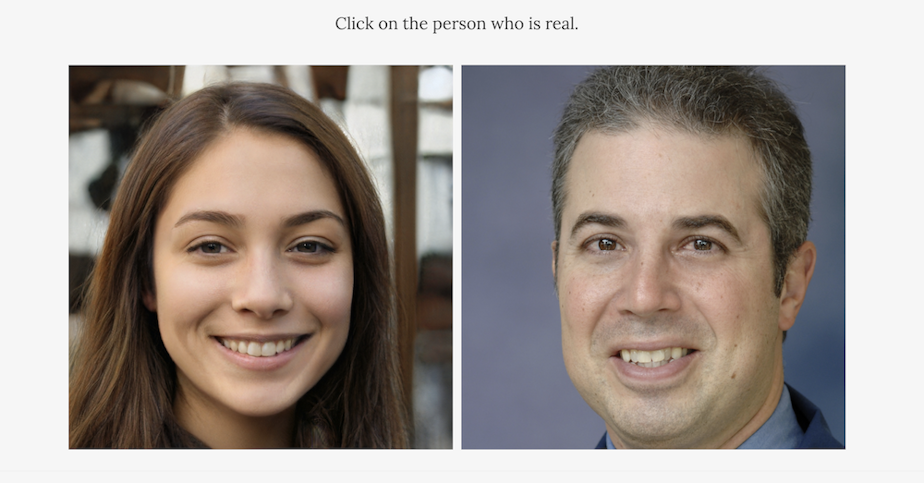

And you can practice, too. Several websites have been created to help train consumers in deepfake and cheapfake detection, like spotdeepfakes.org and whichfaceisreal.com. Becoming familiar with some of the signs of a fake video or image — such as wonky eyes, errant hair strands, and fuzzy backgrounds — is critical for spotting and stopping the spread of misinformation.

Are we going to be OK?

While the process has been slow, we’re definitely better equipped at fighting misinformation now than we were four years ago.

It’s a difficult job considering that the better we get at detecting misinformation, the better others get at producing it.

While in 2016 disinformation campaigns focused on viral posts and videos, this cycle they’ve become more targeted toward local events, forums, and areas more vulnerable due to a lack of local journalism.

Responsibility falls not just on information consumers but on social media companies to police their platforms and create an infrastructure that targets and takes down misinformation.

In the last year Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Google have taken bolder actions toward instituting and enforcing new misinformation policies, largely due to pressure from the government and their users.

Thanks in large part to updates from public health officials, social media companies were able to create rigorous policies through which they could fact-check misinformation against.

That power, however, weakens when more nuance is introduced, such as when a Washington state chiropractor mischaracterized a Covid study and wound up being retweeted by President Trump.

Fact checking is a critical tool for addressing misinformation, but it isn’t enough to curb its reach and negative effects, meaning misinformation needs to also be halted at the start, at the individual user level, before it’s widely shared.

Misinformation has existed for centuries, and will continue to exist, so it’s up to individual users to look critically at where they find information and how they spread it.

“Are we winning?” asks Jevin West. “I think we’re in the stage right now where we’re behind at halftime and we’d better come into the locker room to discuss how we can be better information producers and consumers.”

You can find some of The Record's continued coverage on misinformation below.

It's been four years – what have we learned in the fight against misinformation?

With the election only two months away, don’t be surprised to see a lot more false and misleading stories like this in your timelines. The University of Washington's Jevin West explains how to avoid spreading it yourself.

Millennial Pink QAnon?

Instagram influencers: the pastel face of QAnon? So says EJ Dickson, a journalist for Rolling Stone, about the social media mavens profiled in “Mom Influencers on Instagram Are Spreading Anti-Mask Propaganda.”

It's getting harder to trust anything online. Is that a bug, or a feature?

Thanks to a proliferation of news hubs and social platforms, our world as guided by the internet is more individualized than ever. While sifting through the noise, is there somewhere we can all trust is true and accurate? Featuring Journalist and Author Richard Cooke and The Center for an Informed Public's Rachel Moran.

Deepfakes 2020

By now, Jordan Peele’s deepfake video of Barack Obama seems like a quaint memory of the past. Deepfakes are alive and well in the 2020 election, and Microsoft VP of Customer Security and Trust Tom Burt is doing something about it.

The Antifa invasion that wasn't

The tangled web of internet misinformation – in this case amplified by the president – exploded onto the Olympic peninsula earlier this spring. The telephone game that led conspiracy theorists to the small town of Forks is unspooled by reporter Lauren Smiley, who wrote the piece "The True Story of the Antifa Invasion of Forks, Washington" for WIRED.

Jevin West on elex disinfo + misinfo

As the election draws closer, beware the posts of the friend-of-a-friend. That’s just one of the tips Jevin West, who’s head of UW’s Center for an Informed Public, had to impart on how to combat disinformation and misinformation around the 2020 election.