The ancient wild

Where I live in Bellingham, Washington, is the ancestral homeland of the Lummi Nation. Sometimes I look out my window, through the trees, and wonder what it was like a thousand, or two thousand years ago, or more.

There would have been giant trees, wildlife everywhere like grizzly bears, eagles, orcas, and salmon. And I picture people paddling in dugout canoes across the water.

The Lummi have been telling stories for thousands of years. My friend Lisa Wilson loves a good story. I’ve asked her to share one that is very special to her and her people. It’s a “creation story." It's about how her people — the Lummi — came to be.

Sponsored

"I am a Lummi tribal member and it's been taught to me that we are the lactamish people. We are survivors of the flood," Lisa says.

The Lummi people are born storytellers and in many ways natural environmentalists. As Lummi tribal member Darrell Hillaire puts it: "It's the lifeway of our people." More on that in a bit.

Lisa becomes quite serious as she tells me the creation story, because for the Lummi, and all the Coast Salish people, it is an important one to get right. Stories are sacred in their culture. So Lisa notes that the story is her memory of the ancient Lummi tale.

"A person in our village, he got warning that there was going to be a big flood. He came to the village to warn the people that we are in for a big flood and that we need to prepare. We needed to build canoes that would sustain this big flood. But in this canoe, we needed to make sure that our youth was going to be in that canoe because they were our future. But we also needed to put in that canoe what our youth and our children needed in the future. So we gathered those things and we put them in the canoe. We tied the canoes together. We put the supplies that we needed into the canoes. And all of a sudden, the rain started happening. Just like the warning. And it rained for many days and many nights and they could no longer see land.

The people were in their canoes for a long time before the rains stopped. Finally, it did. The water level dropped and revealed the land once again. The people set up their villages with long houses and started to gather food. Groups of people headed out to gather ducks in one area, some gathered salmon in another, others went for oysters and shellfish and octopus. And as they did this, the people started to spread further apart and settle in different areas.

Sponsored

"So the oldest person in the village started to worry that we were not going to be one people. So he gathered the people together. They all brought their foods and had a dinner to discuss how they were going to evolve as a people. And so they came up with that, you know, we can separate as a people, but we are the lactamish people. We are the survivors of the flood, and we cannot forget that. So they told the people that if they spread off and they rename who they are, they need to keep the 'ish' at the end and that will identify who we are. So, you know, we had the Duwamish, we had the Swinomish, we had the Sammamish, we had the Skykomish and those are the people that separated. But we always knew who our people were."

When Lisa tells stories like this, she thinks about those ancestors.

"I feel really grateful that they did survive the flood, and I feel grateful that it's not just survivors of the flood, but our people are just survivors, period, of whatever that has come," she said. "Whatever adversities that have come before us, we have overcome them and we've adapted. We were people that had to adapt to things that we didn't know. But not only did we adapt, we thrived."

The Lummi call themselves "the salmon people” and "the people of the sea." They have lived on the Pacific Northwest coast for more than 10,000 years — from “time immemorial” as I’ve heard them say.

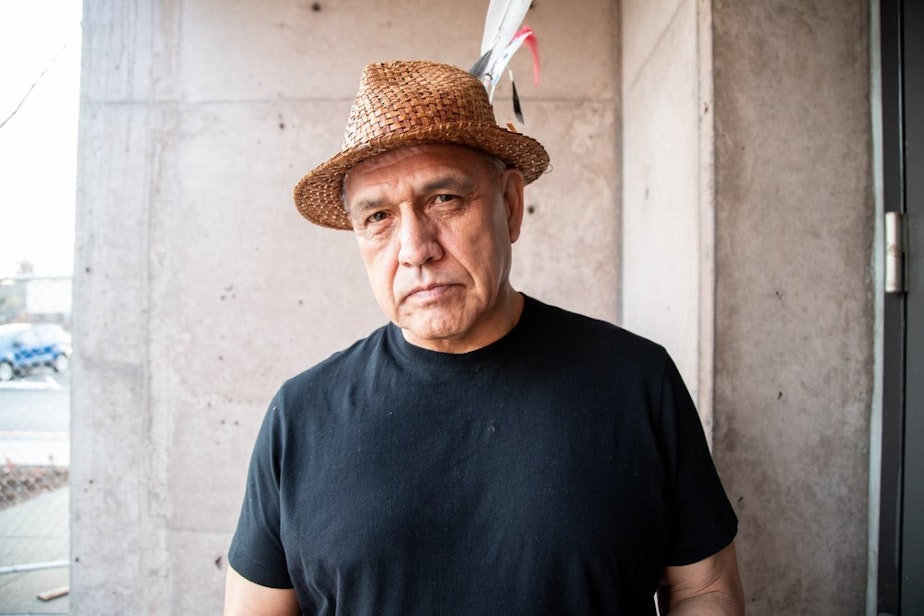

Through their long history, stories have been their lifeblood, a verbal documentation of their lives. Elders are like the keepers of these stories — they keep them alive by telling them and sharing them. Darrell Hillaire is one elder who has been doing just that.

Sponsored

Keeping stories alive

Darrell stands at the mouth of the Nooksack River as he tells me about how the sound of a river can tell you what time of year it is.

"Water’s sacred to our people," he said. "Everything we do is signaled, is forecast through our relationship with with the water here, with the animals here, with the salmon here. Our biological clock is attuned to what nature gives us. Different times of the year."

Darrell's great grandfather knew things like this, and he knew his people's stories. As he endeavored to preserve them, in a way, his great grandfather created a new story to tell.

Sponsored

"Our people lived, you know, and they followed the salmon, you know, and they had villages in the San Juan Islands," Darrell said. "They had villages along the pathway of the salmon as they returned to the Fraser River. So we had many homes."

That changed when settlers came and disturbed this livelihood. When Darrell's great grandfather Haytaluk was a young boy, and treaties were being drawn up in 1855, he was aware that his culture was eroding.

Darrell describes times when tribal members were being arrested for practicing their beliefs, even for telling their stories. This greatly influenced Haytaluk.

"So what did my great grandfather do? He got everybody dressed up and painted up and went out into the roads — ‘Here I am. Come and get me.' And they didn’t arrest him or anything because he had such a powerful voice of unity, a powerful voice of creating understanding amongst the people. And the people enjoyed what he was doing so they had no say."

Haytaluk understood the power of story and performance. So in the early 1900s he created a dance and storytelling group that took performances on the road. This enabled them to share their language, songs, and dances with the newcomers. It was a positive way to remind them who the Lummi people were and what they stood for: to invite unity.

Sponsored

The group included Haytaluk’s grandchildren. He named it “The Children of the Setting Sun.” Their stories and dances reached people all through the Northwest by the time Haytaluk passed away at the age of 98.

"Before he died, he left these instructions — to keep my fires burning," Darrell said.

The words had a huge influence on the grandchildren and among them was Darrell’s great uncle, Joe Hillaire. Darrell was destined to follow in their footsteps and tell stories.

Joe continued the legacy all the way through to the '50s and '60s. Haytaluk's grandchildren also picked up the dances and storytelling.

"And they did right up until a lot of them had passed away ... they just followed the instructions of my great grandfather to go out and remind the people that we're still here."

The stories persisted through the decades, when Native Americans fought for self-determination in the 1960s; and for their right to fish salmon in the 1970s; and for self-governance in the 1980s and 1990s.

"Well, for me, it's the lifeway of our people, you know, to pass on our history," Darrell said. "And when you have that, then you're able to care for this place that we live in. That's why our tribe are such warriors for protection of the environment. of stopping development where it's not needed, of making people understand that, you know, you can't be doing things to the water and to the land because our stories come from there. And our stories are carried in our hearts."

Darrells also says that they seek "understanding through storytelling."

"When you think about the history of native people in this country, and the founding of this country — which this country being the United States of America — that the real history has not been told in history books ... in our institutions. So we have to begin to tell our own story. And that's emerging now through our language, which is being rediscovered through our children; children actually stepping forward and practicing our way of life at a young age rather than later in life. So it's actually being learned in the womb now. And I think that's really cool because for a few generations it was taken away."

And he means that — literally in the womb.

"Our mothers and our grandmothers are going to the smokehouses now while they're carrying, you know. And so when you're in the womb, your cells are being filled with the ancient stories. They're being filled with the language in the songs and the cadences of our people ... that was always true until the newcomers came here and our family structure was destroyed. So putting that back together, it's just really cool to understand 'Oh wow, this is in our DNA.' And we carry that in memory. That way of life pre-contact."

There is power in stories, felt by those who have been telling them for the longest. Stories remind us about the past, and just as importantly, they can teach us about the future. Stories can even help us defend the wild.

THE WILD is a production of KUOW in Seattle in partnership with Chris Morgan Wildlife and The UPROAR Fund. It is produced by Matt Martin and edited by Jim Gates. It is hosted, produced and written by Chris Morgan. Fact checking by Apryle Craig. Our theme music is by Michael Parker.

Follow us on Instagram (@thewildpod) for more adventures and behind the scenes action!