Seattle Afghans to new arrivals: 'Recognize the power we all bring with us'

Read a version of this story that has been translated into Dari here.

H

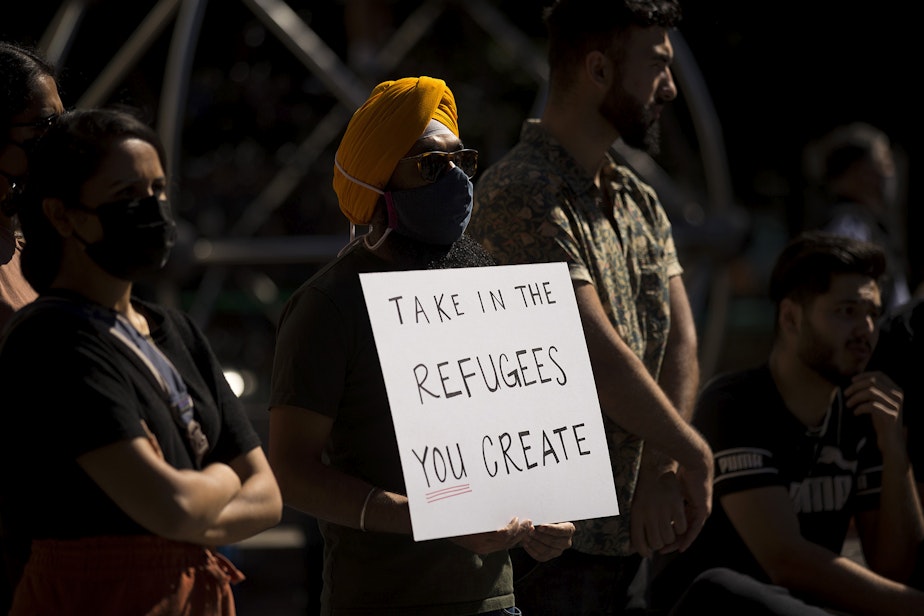

undreds of Afghan refugees are preparing to start a new life in Washington state, after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in August, ending a 20-year occupation.

Most Afghan families currently arriving in Washington state are slated to come to Kent and Seattle, according to numbers provided by Gov. Jay Inslee’s office.

KUOW spoke with four Afghans who fled Afghanistan years ago, seeking safety from the violence that has engulfed their country.

They discussed the challenge of navigating the systems in our state, balancing their assimilation into American life while maintaining their roots in Afghan culture, and managing their trauma and pain of being separated from the loved ones left behind.

RELATED: Seattle Now: A local effort to help Afghan refugees

“[The people of Afghanistan] sacrificed so much and risked their own safety, wellbeing and even lives to save U.S. troops and now we are abandoning and betraying them in the worst possible way,” said Aneelah Afzali, executive director of the American Muslim Empowerment Network at the Muslim Association of Puget Sound.

Locally, she said there is overwhelming support for Afghans arriving as refugees, and “that’s beautiful to see.”

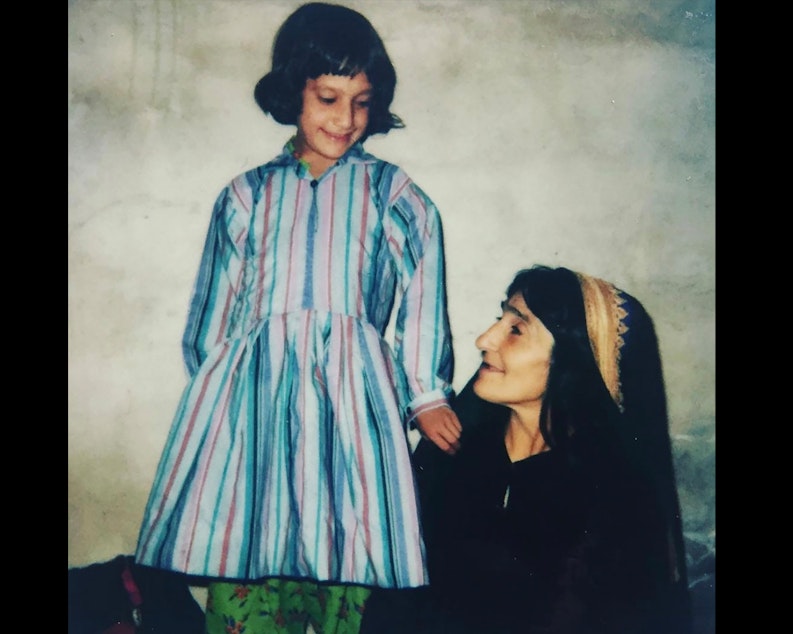

Zarby Kakar: Arrived 1985

In Afghanistan, Zarby Kakar, 46, remembers her family’s life as farmers as a beautiful one.

But during the nine-year Soviet-Afghan War, unmarried women were being kidnapped by the Mujahideen. Kakar’s mother married off her older sisters, in a rush to protect them. Kakar was the youngest of 10 children. Her mother planned to take her and leave for Pakistan, where Kakar’s older brother would meet them.

So in 1985, at the age of 9 and in the midst of the war, Kakar came to the U.S.

Kakar was fortunate to have a brother already living in the Lake City neighborhood, she said, and to relocate to Seattle. The politics locally were different then, before 9/11 and the Donald Trump presidency, she said. It was a time in which she and her mother were “welcomed with open arms.”

Kakar’s mother made a special doll for their journey. Kakar gave the doll a name, Meena, and a birthday, April 10.

“That doll was everything to me,” she said.

Sponsored

On their journey, Kakar and her mother traveled mostly at night, to stay out of sight, and moved on foot and by car.

Every evening, as they rested during their journey, in one hand Kakar would hold on tight to Meena, and in her other small fist, she would grasp her mother’s skirt.

“I would wake up with my hands hurting because I was holding onto a doll and my mom so tight, so that nobody takes Mom away from me,” Kakar said.

One night, she lost Meena, her prized doll.

After three weeks of travel, Kakar made it to Pakistan with her mother, and was given a new hand-made doll, and after reaching Seattle, given a Cabbage Patch Kid.

Things weren’t easy in the beginning. She had not attended school before nor had she been separated from her mother. She didn’t trust the people who said her mother would be there when she returned home from school.

“It's not only difficult to come and get started in an environment you know nothing about,” Kakar said, “but back home, you leave everyone and everything that once was familiar to you, once that you cared about.”

Her agony came from feeling homesick, she said, and separated from her eight siblings who stayed in Afghanistan.

As Seattle was poised to receive refugee families from Afghanistan, Kakar has been busy helping with preparations.

She’s asked that schools, where refugee children may attend, offer counseling instead of sending students to detention for misbehaving, “because these kids that are coming with their parents, I know exactly the trauma they have,” she said.

To people who may be nervous about incoming refugees she said, “If you want to know the meaning of resilience, get to know an Afghan. Because Afghans, that's all we know, because we have never had a choice.”

To the Afghan refugee families that are coming to the U.S. she offered words of comfort.

“I know right now our music, our beautiful anthem, is silent,” she said. “But I know deep down in my heart, with all the tests and all the wars that Afghanistan has been through, we will sing our anthem again, and we will dance again, and we will drum our drums again.”

Aziz Jamali: Arrived 1991

Nearly 30 years ago on Oct. 31, 1991, Aziz Jamali arrived in Seattle with his parents, two of his sisters and two of his brothers. Jamali was the oldest at 18, and excited to be in a city free of violence.

The family of seven at first lived in a two-bedroom home in the SeaTac area.

“We were kind of nervous, where we will be living, what kind of job we will have?” Jamali said. “What our future will be.”

Jamali’s family met others from Afghanistan, who taught them how to navigate the complexities of Seattle systems.

In Kabul, where Jamali is from, every night he heard the sounds of bullets being fired. Sometimes the military would force young men onto the battlefield, something he feared would happen to him.

In Pakistan, where they immigrated as refugees, Jamali lived under a tent, in 120-degree temperatures, with no water or electricity. Under these conditions he passed the 12th grade.

In Seattle, he was determined to continue his education, but he needed money for tuition.

At first, he started attending an ESL (English as a second language) class at Highland Community College, unaware that it cost money until the instructor asked him to pay.

“I came from a country where education was free,” he said, “to a different country where nothing is free, including education.”

As a student in Seattle, he noticed how easily his classmates could grasp the concepts in their textbooks, while he had to read the same book more than once. He was often the last person to leave the library.

“I went through traumas,” Jamali said. “I came from a warzone. It wasn't easy for me to transition so easily in this society.”

On top of this, he delivered the Seattle Post-Intelligencer and The Seattle Times to help support his family in the U.S. and family that remained in Afghanistan, a responsibility Jamali said often falls on those who head the household in Afghan refugee families.

At school, he studied engineering, and dreamt of working for Boeing, sparked after he toured their factory as a student.

“Engineering students can communicate easily, because it's a science language, and less English,” he said.

Jamali’s dreams were eventually realized after Boeing hired him as a mechanical engineer in 2000, nine years after moving to the U.S.

In his message to newly arriving families, he stressed the importance of patience.

“Many, many challenges will be ahead of them,” Jamali said. “It's not easy. So finding a job, paying for the rent, if they want to go to school, finding money for their school. These challenges are ahead of them. Be patient. If they're here in this state, they are in the right place.”

Aneelah Afzali: Arrived in 1983

In the late 1970s, Aneelah Afzali’s father was serving in the Afghan army and saw the signs of impending war. The Soviet Union was preparing to launch its nearly decade-long Communist invasion, and her father wanted to get his wife and five children out of harm’s way.

Afzali, now 44, was a toddler then, and doesn’t remember leaving Afghanistan. But growing up, her parents shared the story of that difficult journey, including not having enough passports to escape, hiding in a truck, and after reaching Pakistan, being short on money for their plane tickets to Germany.

As serendipity would have it, Afzali said, a friend came to visit the family in Pakistan. The friend had sold the family’s possessions, left behind in their care, providing the family with enough money to buy their plane tickets.

“In the unbelievable way things worked out, there's proof of a greater power,” Afzali said. “There's a divine force trying to assist you.”

The family relocated to Germany as refugees, and then in 1983 moved to Union City, in the Bay Area of California, as part of the family reunification program.

As a child, Afzali’s parents took on various jobs to provide for their family. Her father worked at a machine shop and gas station, while her mother worked at a beauty parlor and provided childcare. On the side, the family also opened a hot dog stand, and sold goods at a flea market.

At home, the children spoke Dari, the Afghan dialect of Farsi.

“My parents didn't want us to lose our cultural identity,” Afzali said.

After the family relocated to Portland in the late 1980s, they provided janitorial services for a few months before Afzali — in the 7th grade at the time — helped her parents fill out the necessary paperwork to open their first business, a video store.

“I remember thinking about the business paperwork, ‘This is a language I don't understand.’” Afzali said. “It's English, but it's not English, because it was legalese.”

It was this experience that partly inspired Afzali to attend Harvard Law School. She graduated in 2003 and moved to Seattle.

“Recognize the power that we all bring with us,” Afzali said, addressing the newly arriving Afghan families. “The Afghan people are proud, resilient people.”

Afzali was critical of the way the withdrawal was handled and said Afghans coming to the U.S. are the fortunate few, and that many Afghans who risked their lives to help U.S. troops have been abandoned in Afghanistan.

“These people who've arrived here, who've made it here, are starting a new life. And they should know that they have so many friends and allies and welcoming neighbors who want to integrate them, who want to be friends with them, and build with them, and grow with them.”

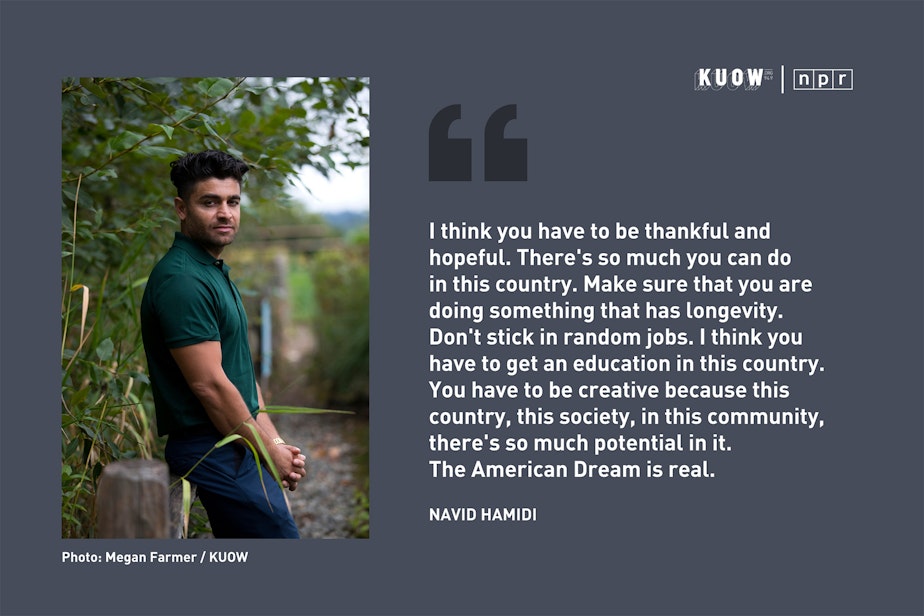

Navid Hamidi: Arrived 2014

It was pouring rain when Navid Hamidi, 23, exited the SeaTac Airport in 2014, after arriving from Afghanistan. Hamidi was overcome with nervousness and excitement as he peered out the window of an old van that smelled of cigarette smoke.

A caseworker drove Hamidi to his brother’s apartment in Kent and when they arrived, the driver said “Welcome to America,” before Hamidi ran to his brother’s front door.

For four days he stayed in the apartment, sitting, sad, aware of the distance that now separated him from his family and hundreds of cousins that he was close with, back home.

“The culture in Afghanistan is just like, literally, there's not a night, regardless if it's weekends or weekdays where you don't have guests or you don't have company, but you lose that right away in one night,” Hamidi said.

Some Afghans come from villages, he said, leading to unimaginable culture shock when they arrive in the U.S.

However, it wasn’t Hamidi’s first taste of separation or travel. At 18, he took up employment with the U.S. government, after the U.S. invaded Afghanistan and the Taliban left, in 2001.

His work took him from Kabul to the Paktika Province on the Pakistan border, and to Moscow, before returning to Afghanistan.

He had already been accustomed to the violence.

His mother gave birth on the floor in a hospital with broken windows, as sounds of war rang out in the background. As a child, he witnessed the Taliban’s arrival in Kabul, and five years of the brutal regime.

Hamidi described a laundry list of traumatic events that, to him, had become normalized. He saw someone shot in the head, someone blown up, a neighboring family killed.

“You don't lose sleep if you're exposed to that level of violence all your life,” he said.

The Seattle area offered an opportunity of safety.

At first, the hardest part was navigating the complex systems — learning how to apply for financial student aid, or Medicaid — even navigating the bus system, Hamidi said.

Sometimes a six-minute bus trip to his job at TJ Maxx became an hour-long journey stewed in confusion.

He also had to advocate for himself. When a caseworker offered Hamidi a job on an Alaskan shipping boat, one that required that he be at sea for months at a time, Hamidi declined.

“This is the type of advice people receive when they come here,” Hamidi said, noting that the resettlement agency told him to take up employment anywhere.

He said newly arriving Afghan families needn’t settle for a career path they aren’t happy with in the U.S., that financial assistance for college exists, and that unlike in 2014, when he first arrived, there is a large community of Afghans that can help immigrants and refugees navigate the systems.

“I think you have to get an education in this country,” he said. “You have to be creative because this country, this society, in this community, there's so much potential in it. The American Dream is real.”

Helping newly arrived Afghans navigate the system is part of the work he’s doing now, as the executive director of the Afghan Health Initiative.

“They just don't know what to do, like they’re lost,” Hamidi said.

They’ll ask Hamidi about next steps, to which he’ll advise that they find people to talk with, and just take things day-by-day.

“It's really hard for an individual to build a life and just leave it behind,” he said.