Local explorers believe they've found Puget Sound's deadliest shipwreck

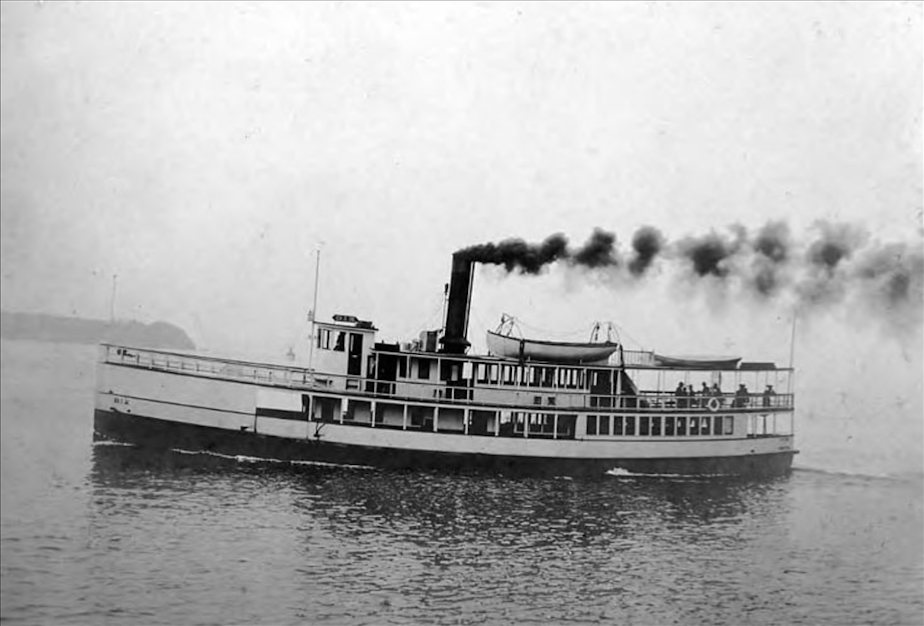

In 1906, the Steamship Dix was shuttling passengers from Colman Dock to Port Blakely when it crossed the path of the SS Jeanie. After the SS Jeanie rolled the SS Dix, the latter's passengers scrambled for safety, with dozens tragically sinking aboard the vessel.

More than 100 years later, local shipwreck enthusiasts believe they've found the steamer's resting place in Elliott Bay.

O

n a calm morning, masts rattle on the sailing ships of Elliott Bay Marina. In the distance, state ferries make their landing at Seattle's Colman Terminal, just as they have for decades.

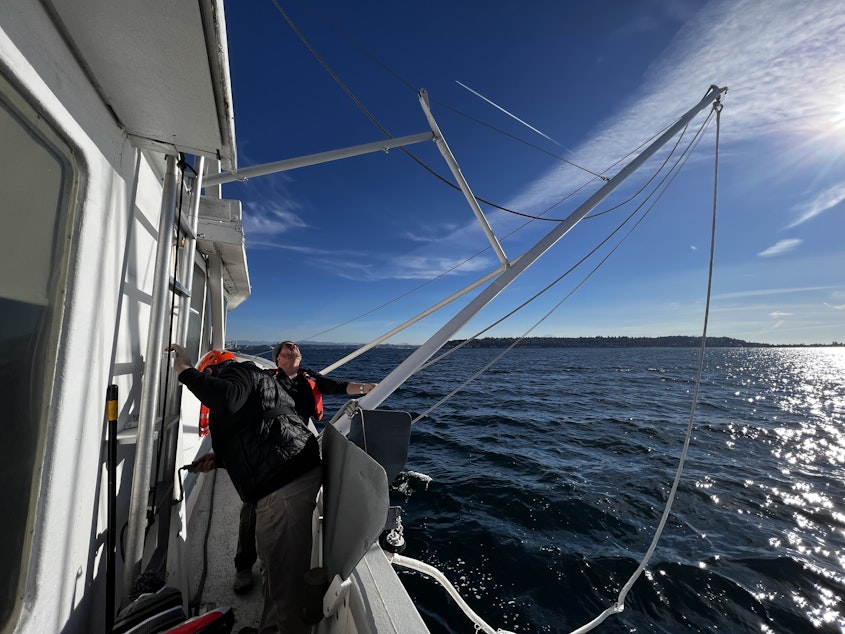

Aboard the Seablazer, the research vessel of Jeff Hummel's company, Rockfish, Inc., the view is a window into the past. Today, his ship is heading out toward the center of Elliott Bay, a journey that isn't so different from the steamships that ferried the passengers and cargo of the past.

In the century since its tragic collision, the wreck of the SS Dix has become the stuff of infamous legend. Ahead of commonplace travel by car, the Dix was part of Puget Sound's "Mosquito Fleet," a group of passenger steamships that functioned similarly to today's state ferries.

The cause of the wreck is still inexplicable. Shortly after leaving the terminal, the ship's captain went below deck to begin taking passenger fares — a job typically reserved for what was called a "purser." With the mate in charge of steering, the ship drifted into the direct collision course of the SS Jeannie, a considerably bigger vessel, which rolled the Dix onto its side, filling it with water.

At least 39 of the ship's 150 passengers died in the wreck, which remains Puget Sound's deadliest.

Sponsored

Even though the wreck was documented in newspapers at the time, the final location of the SS Dix on the floor of Elliott Bay has remained a mystery.

But Hummel, an experienced shipwreck expeditionist, believes he's found it.

"We know that when it hit the bottom, it sort of made like a crater in the bottom of Elliott Bay," Hummel said. "And so the question is, well how did the bow get hit? Did it get run over more by the vessel? At this point, we don't know the answer to that question yet."

A

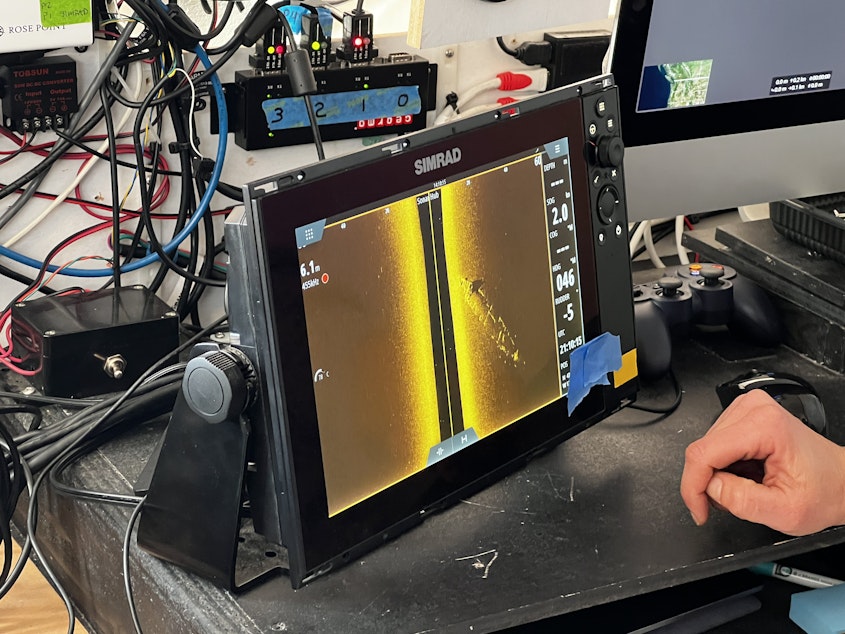

fter a 30-minute ride on a clear and calm day, the Seablazer drops its stabilizers and deploys a side-scan sonar to begin searching for the SS Dix. In the cabin, the radar shows white specks — likely fish — blinking on either side of the ship. But slowly, the faint outline of a broken oval begins to register.

The crew shouts to Hummel — they've found it.

Sponsored

"You hit it really well. Well done!" he shouts to the captains manning the wheel.

From here, the sonar is pulled back up as a remotely operated vehicle is dropped in its place; Hummel wants to get a camera in the water to get a closer look. As the operator drives farther down, the video feed looks like it's going into hyperspace, rushing through specks of dirt and bubbles.

When the wreck appears, the hull is covered top to bottom in white sea anemones.

Sponsored

"Those bright things you see sticking upwards, each one of those is a major timber," Hummel explains. "They're very unfriendly to a robot."

For the last 100 years, the actual location of the SS Dix has been the subject of debate.

In 2011, a local company named OceanGate announced it had found the wreck in Elliott Bay. At the time, news of the discovery hit the front page of local newspapers. But after further exploration, the company said their find was likely a misidentification.

On the water, Hummel reveals his crew first stumbled upon the site around eight years ago — and they weren’t the only ones to have found it. At the time, it was generally accepted that this particular wreck was a run-of-the-mill schooner.

In fact, for years, Rockfish has been using the wreck as practice to hone its sonar skills for other, more technical ocean searches.

Sponsored

It was after repeated trips and more scrutiny that the crew had an epiphany.

"We realized that everyone was looking at it backwards," Hummel says. "Everyone thought that that stern was actually the bow. And so when you compare it to the photos, nothing lines up — until you flip it around, and you realize that the front, which is kind of crushed a little bit, is what people are calling the stern."

"The major structural items all line up perfectly, and it is the Dix."

Sponsored

This isn't the first significant find for Rockfish.

Last December, the group announced the likely discovery of another legendary Pacific Northwest shipwreck: the SS Pacific, which sank off the coast of Washington in 1875.

After having a piece of the wreck arrested in federal court, Rockfish was awarded exclusive salvage rights for the ship's plentiful artifacts and its cache of gold (for clarity, that gold belongs to the companies who insured it in 1875, with ongoing negotiations over Rockfish's compensation for salvaging that cargo).

As for the SS Dix, Rockfish — and its nonprofit collaborator, the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance — is hoping to leave this wreck alone as a historical grave site.

"Out of respect to those families, we're not touching or doing anything without having that done in accordance with an archaeological plan that has been drafted by credentialed marine archaeologists that are going to be able to direct that and study it," said Matt McCauley, president of the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance.

As of now, Hummel says there isn't a legal mechanism allowing them to protect the wreck long term. Following their typical salvage procedures would only grant partial, short-term protection, so long as the group continued pulling up pieces of the wreck.

Rockfish is currently working with the state of Washington to find a legal solution that would protect the ship without needing to disturb it.

The irony of that philosophy means they may never truly know if this is the SS Dix — at least in an official capacity. But even if there isn't a clear marker that this wreck is the ship of legend, they’re hoping to make the strongest case made thus far.

"Based on its size, its depth, its position, its visual appearance, that of it which we can discern, it is highly likely that it is the Dix," McCauley said. "Is it possible that we made a mistake? Yes, it is possible, because there's no bell, there's no piece of China or something. If the name had been painted on, it's long gone by now because the marine borers have eaten up most of the wood."

"But it's the right size, and the right place, and looks to be about the right age."

Hear the full Soundside segment by clicking the play button at the top of this story.