Salmon catch airlift toward spawning grounds after rockslide blocks their way

An emergency operation is under way to help salmon fly – and help orcas not run out of food.

Canadian officials have started airlifting salmon past a rockslide that has largely blocked the fishes’ path up British Columbia’s Fraser River.

Millions of salmon muscle their way up the Fraser each year to spawn – some as much as 750 miles inland -- making it one of the continent’s most important sources of salmon for humans and orcas alike.

Endangered killer whales feast on Fraser River chinook salmon as the fish migrate past the San Juan Islands on their way to the river’s mouth, just north of the Washington-British Columbia border.

Some 250 miles upriver, salmon determined to reach the spawning grounds where their lives began have been hitting an insurmountable obstacle: a waterfall created when tons of rock crashed into the river.

“We were in conservation mode to begin with before this slide even started, and so now we’re looking at a bit of a conservation crisis,” said Gord Sterritt with the Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat.

Sponsored

The rockslide apparently fell last fall, but was only discovered in June after examination of satellite images of the roadless, sagebrush-lined stretch of river north of Lillooet, British Columbia.

“It’s a very remote area,” Sterritt said.

On Monday, a helicopter hoisted the first sloshing aluminum tank of salmon into the air, to help the fish reach their spawning grounds in the upper Fraser.

Work crews had built a weir, a sort of fish trap, in the river to lure the salmon into a holding pool. Biologists then inserted tiny radio tags in the fishes’ stomachs to keep tabs on their journeys upriver after their 2-mile helicopter ride.

An emergency response team also hopes to make the rockslide site easier for fish to swim past before the biggest salmon runs arrive in the weeks ahead.

Sponsored

Chinook and sockeye salmon are just starting to reach the slide site, with coho salmon migrating later in the summer and fall.

“As more fish arrive, we’ll keep trying to collect them, tag them and ship them farther upriver,” British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations spokesperson Noelle Kekula said.

“Every chinook and sockeye and other fish species that can make it above the slide count[s], and we’re doing everything we can to get those fish above the slide,” Sterritt said.

Workers have been rappelling down the cliff face to pry away loose rocks with pneumatic drills and inflatable rubberized balloons to make it safe for workers below.

On Monday, they blasted away a dangerously overhanging rock the landslide had left behind.

Next, they plan to install a temporary fish ladder and build a series of pools and smaller waterfalls that salmon can more easily navigate.

“Our number one goal is to open up the partial blockage,” Kekula said.

Officials say they’re working around the clock to help the salmon that were already considered endangered before the rockslide made life even harder for them.

Fraser River chinook are the main reason orcas spend much of their time near the San Juan Islands and have become culturally and economically important in western Washington.

Sponsored

The Fraser produces more chinook salmon than all the rivers of Puget Sound combined.

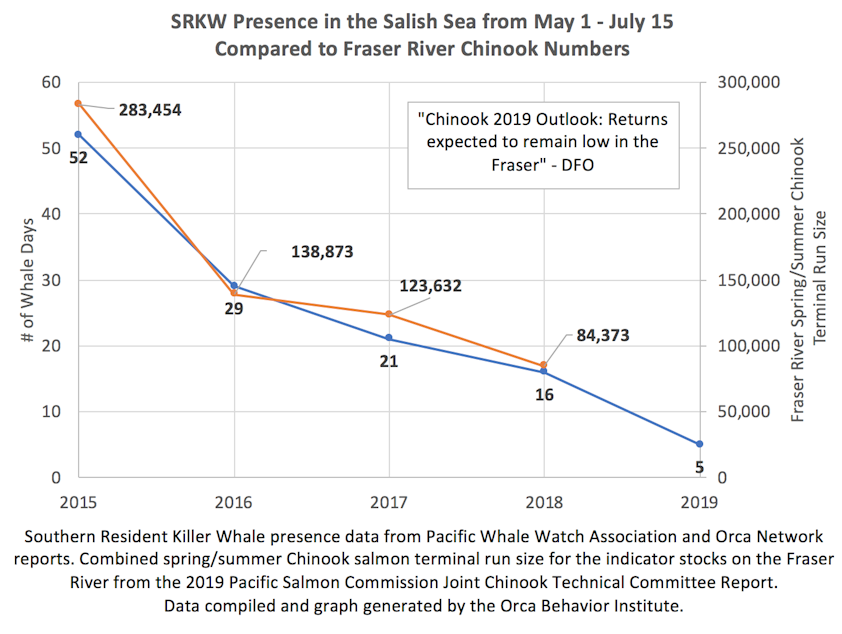

Declining salmon runs in the Fraser have been linked to orcas spending less and less time in their usual habitat in recent years.

Southern resident killer whales — so named because they spent much of their lives near the southern end of Vancouver Island, in the inland waters of the Salish Sea — used to spend weeks or months at a time each spring and summer near the San Juan Islands and Canada’s Gulf Islands.

Since May 6, the southern resident whales have spent just two days in the inland waters of the Salish Sea.