In Rainier Beach, neighbors have a dream, but developers are holding cards close to their chests.

In Rainier Beach, non-profit groups want any development that comes in to help the neighbors who live there now. And development seems likely, as recent upzones raise the height limit on some properties from four stories to twelve. Developers are holding their cards close to their chests. Rainier Beach is prepared to turn to civil disobedience if developers don’t listen.

Gregory Davis leads the Rainier Beach Action Coalition. He says back in 2012, the neighborhood convened around a question: What could we build here to make this neighborhood better?

People said – we need better access to food. "We have young people who need to be healthy, and who are having challenges with the quality of food in the school district." explained Davis. "As a result, they may go to Safeway and shoplift because they’re just hungry. "

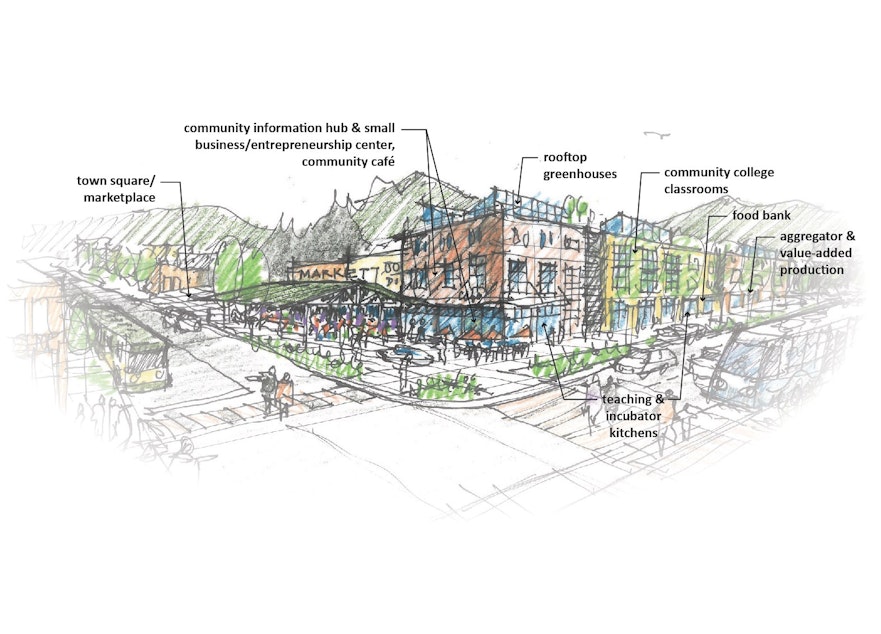

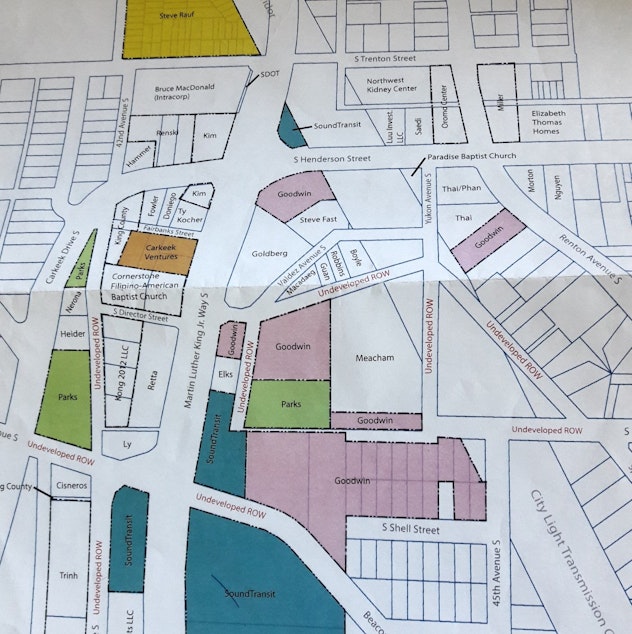

So, the community shaped its neighborhood plan around improving “food security” with an urban farm, farm stands and food education. The crown jewel would be a food innovation center of some kind at the corner of Henderson and MLK, right near the light rail station. The community even had a potential buyer lined up to help them realize that vision. The buyer was Forterra, a non-profit that helps communities purchase land.

Michelle Connor is Forterra’s president and CEO. "We made two runs at that property," she said. "And the seller actively chose to go to a developer, and that’s they’re prerogative. But it’s understandable that the community’s frustrated that, you know, they tried to buy the property."

And now, somebody else owns it. The owner hasn’t told the Rainier Beach Action coalition what his intentions are for the property. I sent messages to him through his lawyer, but received no response.

Sponsored

Davis hopes he can win him over. "Our hope would be that anyone who is developing property in this neighborhood has an interest in what the people from the neighborhood desire and go into that direction. Right?" But we may not know the answer until the owner submits project drawings to the city.

The potential gap - between the developer’s vision and the community’s vision - is a problem in many neighborhoods, Michelle Connor told me. "We don’t have a good framework for how communities and developers can work together in a non-adversarial way."

Sellers need to make profits, and community backed non-profits can’t compete. Connor said it's a profound structural problem. "And I think the situation at the Rainier Beach light rail station should be a call to action for all of us," she said. "What kind of place do we want to be? And that doesn’t mean that somebody who’s a landowner or a developer shouldn’t be enfranchised to utilize their land rights. But surely we can do better than this?"

Sponsored

Forterra learned from the initial failure of the food security development . That effort raised a lot of money, so the next time a piece of property came up near the light rail station, they were able to offer cash and point to a supportive community behind it. That successful land purchase means the food innovation hub will happen after all.

But Gregory Davis and his group are not giving up on the property they originally wanted – the one bought by the developer. They say everything on that corner should have a community benefit.

"Can we control what a developer does on a property that they own?" Davis asked himself out loud, as we walked around the neighborhood. He told me he thinks he can influence the project, either through conversation or through legal tools like the design review process.

Sponsored

And as a last resort, there’s always civil disobedience, he said. "And so when we start blocking development, when we start occupying buildings, and they say 'Why are they doing that?' We gave them the plan on the desires of the neighborhood. And if they decide to go counter to that, then what recourse do we have?"

For a developer trying to make a project profitable, occupation of their property by protesters could add cost and influence decisions.