Workers at Seattle Amazon Fresh store say they've formed a union

It would be the first union in one of Amazon’s collection of grocery stores, which includes Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh, and Amazon Go.

The local union activity is part of a wider trend, as labor shortages continue during the pandemic.

Joseph Fink was nervous when they came into work at Amazon Fresh at 23rd and Jackson last week. They came to work early to post notices about the right to organize.

"All right, we’re walking through the store now," Fink narrated into their camera while recording themselves. "We’re on our way to the employee break room ... OK, I’m just gonna go ahead and post.”

The notices summarized the law. They said it’s OK for workers to organize on company property.

“All right, there we go … that’s it, we’re gonna sit here — and see what happens,” Fink said, just before the video ended.

What allegedly happened next is described in a complaint Fink filed with the federal agency that oversees labor disputes. Fink says a manager hissed at them, disciplined them for sharing union information with coworkers, and told Fink to leave the property.

“After I left that meeting, I was shaking and I was afraid,” Fink says.

KUOW reached out to the manager of the store, who referred us to Amazon corporate public relations team. They didn’t respond.

The National Labor Relations Board is looking into the complaint, and it can’t comment on active cases.

Bullying by managers inspired Fink and others to form the union.

Sponsored

“The managers at Amazon Fresh yell ... they push and they push to the point of exhaustion.”

Fink says the company uses algorithms to track employee productivity at Amazon Fresh. Those algorithms have been blamed for tough working conditions at Amazon’s warehouses, too. It’s one reason people are trying to organize Amazon Warehouses in Bessemer, Alabama, and New York City.

A conversation starter

Since Fink posted the notice, other employees have come forward with stories of what they see as wrong at Amazon Fresh.

“I’ve been there six months. I’ve worked my ass off. I have never got a recognition," Karen Regley said.

Sponsored

For example, one day, Regley spent all day organizing the shelves in the chiller. Normally, workers aren't supposed to spend that long in there. But Regley was inspired, and took photos of her work.

She did not get the response she wanted.

“No one really gave a damn about it. No one cared,” she says.

Regley’s on the fence about joining the union. Others would not speak publicly due to what they described as fear of losing their jobs.

Sponsored

But some employees, such as Nova Rune, have made up their minds.

"I'm joining the union because I feel safer knowing that I have a group of people working with me to make progress in our area of employment," Rune said.

Joseph Fink says right now, this new union is just focusing on protecting its right to organize.

Later, the union will work on other demands to address members' other grievances.

Amazon's stance on unions

Even though Amazon declined an interview, the company's stance on unions has previously leaked to the public in 2018, when a manager training video was sent to the media.

“We are not anti-union," says the animated figure in the video. "But we are not neutral either. We do not believe unions are in the best interest of our customers, our shareholders, or most importantly, our associates. Our business model is built upon speed, innovation and customer obsession: things that are not generally associated with unions.”

During the Bessemer, Alabama union drive in the spring of 2021, the company was not shy about expressing its negative opinion of unions.

When Amazon Fresh managers spoke with KUOW last year, they emphasized Amazon’s relatively high pay and benefits – which include medical insurance starting on the first day of work, and paid tuition so workers can go back to school to learn a trade.

Historical echoes of Ford and General Electric

That approach looks familiar to Margaret O’Mara, a history professor at the University of Washington. She says history shows that offering enough benefits can take the wind out of the sails of union drives.

“And this goes, you know, back to the nineteen-teens and Henry Ford announcing his five dollar day, which doubled the effective take home for his workers, as a strategy for recruitment and retention, but also as a way to prevent unionization and labor organizing.”

But the gap between rich and poor back then gave the labor movement a lot of oomph. And that movement made major gains in the '30s and '40s.

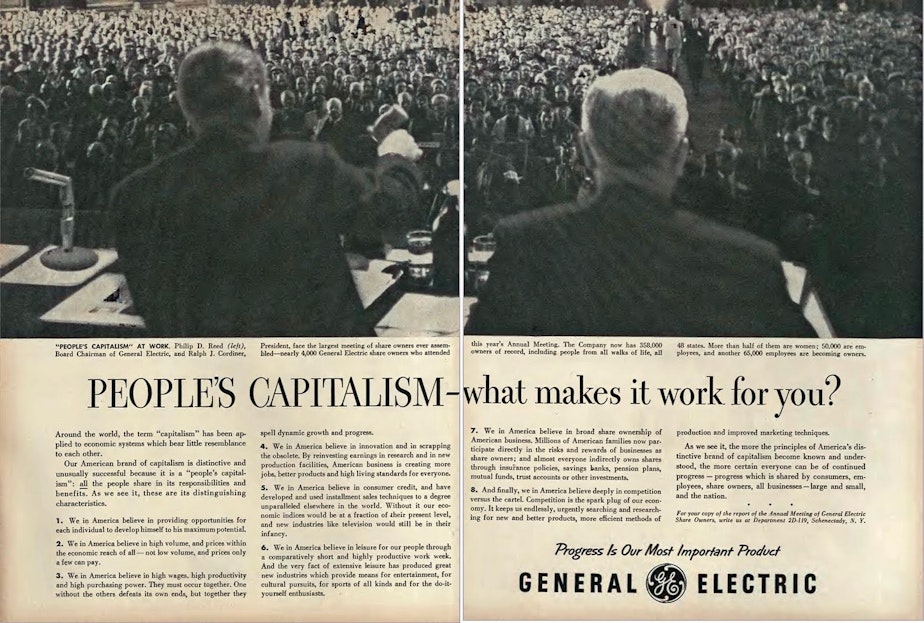

Later, General Electric picked up Ford's message that unions could be rendered unnecessary if companies are generous with their workers. A print ad from Time Magazine in 1956 highlights this way of thinking.

"We in America believe in innovation and scrapping the obsolete," reads the 1956 ad. "By reinvesting earnings in research and new production facilities, American business is creating more jobs, better products and higher living standards for everyone."

"Progress is our most important project."

Lines like these echo messages Amazon puts on billboards in major cities today.

The labor movement lost ground in the last decades of the 20th century, O'Mara says. But factors like the gap between rich and poor today, the pandemic, and the labor shortage have all come together to revive interest today.

The National Labor Relations Boards says petitions for union elections rose 30% last quarter.

“Now, Joe Biden ... President Biden, last year, when the Bessemer workers were organizing, actually said we’re in support of this, which is the first time that a president had said something that explicitly in support of organized labor in a very, very long time,” O'Mara says.

It's unclear how much historical ideas about unions, or even Amazon's behavior during union drives last year, influence Amazon's policy today, especially since the company reached a settlement with the National Labor Relations Board in December 2021, pledging to change its behavior.

The notice Joseph Fink received in an email from Amazon that they later posted on the walls of Amazon Fresh is a product of that settlement.

How the company responds to this union in Seattle, and how it responds in other places where unions are forming will offer clues as to how much the company has changed.

Just a few workers gathering together to discuss problems

The new union effort at Amazon Fresh is just getting started. Right now it’s just a few workers gathering to discuss problems together. It can’t represent workers at the bargaining table until it has an election. It doesn’t collect dues, and it isn’t affiliated with a bigger, more established union.

That approach has drawn some criticism from some labor groups. Tom Geiger is a spokesperson for the local UFCW chapter, which represents workers at larger grocery store chains.

Geiger says a bigger union can help protect its members, but he says a tiny union is more at risk of getting crushed. Its organizers could be fired for unrelated reasons.

“And just think about how that would feel if you found out that a coworker who had was interested in joining the union had been fired," Geiger says. "Obviously, that’s going to have a negative impact that’s gonna serve its purpose, which is to intimidate a worker against forming a union. It’s the reason why the employers do it.”

Leaders of this new union at Amazon Fresh are still trying to build up their membership. Joseph Fink says they hope it can eventually expand to include fulfilment centers ... hence the inclusive name "Amazon Workers United."

At this time, there have been no talks between union organizers and Amazon.

Is this really a union?

People may be familiar with news reports of formal union drives, such as the one at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer Alabama (which is currently holding a second election). Such news reports often feature dramatic stories about companies and organizers each trying to woo workers to their side.

So it may come as a surprise that workers at the Amazon Fresh at 23rd and Jackson in Seattle could simply declare they have formed a union.

KUOW asked for clarification on this from Wilma Liebman, former head of the National Labor Relations Board.

"Nothing formal is required to use the title 'union,'" she explains. "A group of workers at a workplace could decide to form their own organization and call it a union if they wish."

The Supreme Court has found that even groups of workers that do not refer to themselves as a union have the right to strike, Leibman says.

Given the low bar for referring to a community of workers as a union, this raises a question. Is this union at this Amazon Fresh store in Seattle really the first? Other groups of workers at Amazon's Whole Foods locations have also claimed to be organizing workers. Under this inclusive definition, some of these groups may have equal or stronger claim to the title of "first."

Things get more complicated when unions wish to represent workers collectively at the bargaining table. To win that right, they must hold an election, and demonstrate a simple majority of workers in that job class support the union.

RELATED: Unions are getting lots of attention these days. A labor expert explains why

It is petitions for elections like these that rose 30% last quarter. Leibman cautions us not to read too much into those numbers though, for not every one of them will result in a union.

But regardless of whether this union at Amazon Fresh pursues this route, Liebman says the workers' right to "protest, to seek to deal, and to act concertedly," is protected under the National Labor Relations Act.

___________________________________________

Correction: Tom Geiger's title at the local UFCW has been corrected.

Clarification: Wilma Liebman provided more precise language for her quote in the final paragraph regarding what rights are guaranteed for unions, without elections, under the NLRA.