What ‘Unbelievable’ teaches us about responding to stories of sexual assault

When Marie told Lynnwood police she had been raped in 2008, she was charged with making a false report.

Then two female detectives in Colorado tracked down her rapist — after he had raped women in that state.

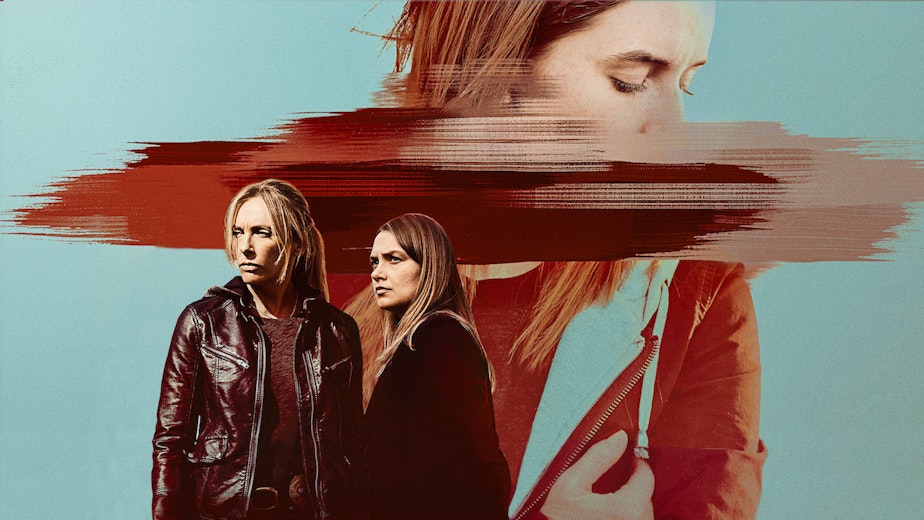

Now, more than a decade later, the scripted miniseries ‘Unbelievable’ on Netflix is telling Marie’s story.

Ayelet Waldman, one of the show’s co-producers, talked to The Record about trusting people’s accounts of sexual assault.

For Waldman, "Unbelievable” is “a story of two different police investigations and the ramifications of not believing women when they come forward with their stories of being sexually assaulted.”

The first police investigation was in Lynnwood, Washington, where a man broke into Marie’s house and raped her at knife point.

Marie took the right steps, Waldman said. She called the police and made a statement. But the police began to doubt her story, and Marie’s two former foster mothers came forward to say that they didn’t believe that Marie had been raped. Eventually, Marie was forced to “confess” that she was making up her story, and she was prosecuted for filing a false complaint.

Marie recanted her story of rape under police interrogation. Waldman said the miniseries highlights how interrogation techniques can force people into false confessions.

“The process of interrogation is brutal,” she said, “and seems often designed to elicit — not a true recounting of what happened, but rather a confession, false or not.”

Waldman said that the Lynnwood police’s decision to prosecute Marie “was inexplicable and horrifying, and they bear tremendous responsibility for it. Furthermore, this is a police department that had at the time an unusually high rate of sexual assaults being dismissed as false claims.”

"Unbelievable" asks viewers to examine their assumptions about how victims of sexual violence respond to that trauma. Waldman pointed out that Marie experienced the “kind of rape that most people are comfortable calling rape.”

“A guy broke into Marie’s apartment in the late night, early morning, and raped her at knife point,” she said. “This is the kind of rape that everyone would consider rape. Even the most sexist among us.”

“And even then she wasn’t believed. And why wasn’t she believed? She didn’t express her trauma in a way that made everyone comfortable,” Waldman said. “She didn’t express her trauma like a victim on 'Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.' She expressed her trauma in a way that was unique to herself. And the men who were charged with protecting us and protecting her refused to recognize that as acceptable.”

But Waldman said that the show isn’t just a condemnation of the police. Instead, it implicates the entire community — including the press.

“What’s devastating in this case is the way in which the entire community turned on Marie,” she said. “She was the victim of harassment. The media immediately latched onto this story in a way that they never had to the story of the rape itself. So they reported on this lie — that this girl had falsified a rape charge — but they hadn’t been as eager to report on the sexual assault itself. And I think that’s really telling.”

“She was attacked by friends, she was harassed by strangers. She was tormented.”

“I think that says a lot about all of us,” Waldman said. “About how we behave when a woman reports on her experience.”

Marie’s rapist was apprehended by two female police officers in Colorado who worked across district lines to solve a series of rapes in that state. He pleaded guilty to 28 counts of rape in Colorado and is now serving more than a life’s sentence in prison.

Waldman said that the work of those two Colorado cops was a stark contrast to the response of the Lynnwood police officers.

“Their attitude was ‘trust and verify,’” she said. “Trust — that when someone calls the police and says she’s been raped — trust. And then verify. Like you would with any other accusation of any other crime.

“This is clearly a story about how certain women — disenfranchised women, young women, and this experience is even more common with women of color — are disbelieved when they tell their stories of being sexually assaulted.”

“This show is unabashedly feminist, unabashedly pro-woman, unabashedly, in a sense, political,” Waldman said. “That’s what people are responding to.”