What happened after I blacked out — and why didn’t one of those young men intervene?

A

t my university – 1992, maybe 1993 — I was a new sorority pledge and was taken, as part of an initiation, to a fraternity party.

It was a party they hosted every year for new pledges, where we were fed lots of Jell-O shots and then given cans of whip cream and shaving cream and told to cover each other.

I did what I was supposed to (I can't even imagine having the gumption to say “no thanks”), and what seemed like minutes later – because I blacked out – I was in a large room with showers running. It had pink tile and a small opening.

Several other girls and I were on the floor, soaking wet, some clothes in piles around us in the running water. I was mostly naked.

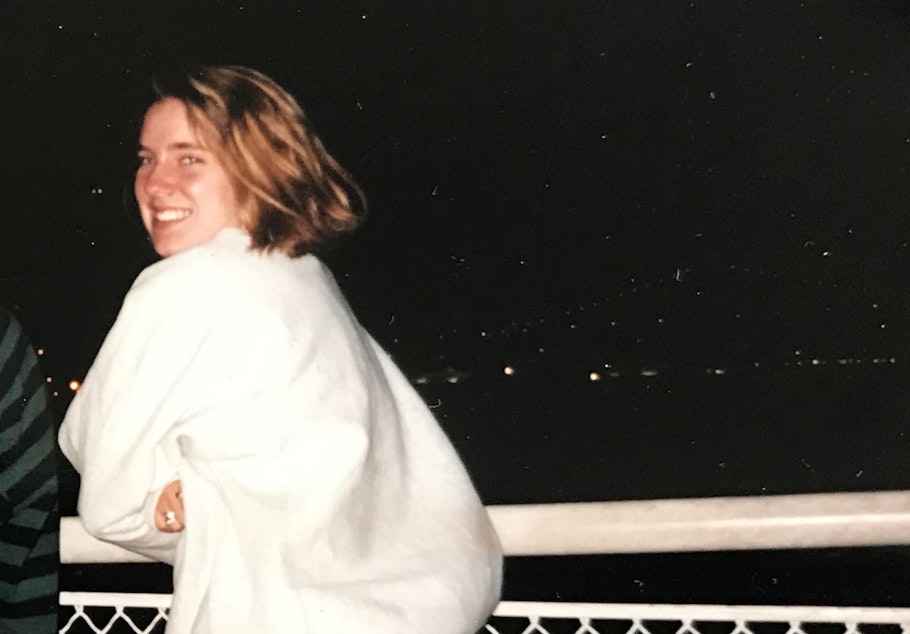

I promptly vomited to howls of laughter from the “brothers” standing in throngs around us cheering. I grabbed some sopping wet garments, and pushed my way through them, down some stairs and out into the night.

I walked the long way home in the dark. I didn't have my shoes, and I was thinking about how I was going to get them back because I really liked them. White loafers with fringe and gold faux military insignia — very nautical. I eventually found a street I knew and from there found my way home to my apartment. I was still really drunk, and numb in the (maybe) October weather.

I don't remember anything really: who took my clothes off, how I got upstairs, or how I got dark bruises on my knees and shins. I don't remember the fraternity, though I knew which direction it was. I was sick as a dog for days, in ways that hinted at what happened to me.

Afterward, no one in the sorority talked about it at all – we had Big Sisters who had taken us there that night. Nothing. Totally normal. They did this every year. I simply floated in my life, and blocked this out. No emotion, low-affect, numb, asexual. I stopped attending all functions and started getting letters saying I needed to attend to maintain my standing, and I told my parents I was quitting the sorority.

They begged me not to quit, because how else would I make friends? This was something that seemed to worry them a lot, because the year before I had tried to leave this massive school where I knew no one. I certainly didn’t tell them about what happened, because I would have gotten in trouble for drinking.

You may know me and see that I don't like to be touched, though I try with people I trust. There is a careful suppression of sexuality, a rigidity of being, and a constant exhausting calculation of what is safe and what is not – that A LOT of women do constantly. I disconnect from my body a lot, and feel like an undercurrent of what I am about, trying to find a path back to my body, to loving it.

I feel foolish when I overreact. I had my husband wait for me the other day outside a restroom, because I had a creepy feeling. I couldn't go in the bathroom unless he stood there. My experience is neither unique, nor special, nor the worst. It is common, probably like those of so many women you know.

What happened to me when I was blacked out? To any of those 18-, 19- and 20-year-old women? Why didn't one of the young men run in and turn off the water and wrap their coats around us, and shout for this to stop. Probably because this event happened every year.

And who were those young men who saw me splayed on wet tile, before I came to? They wore polo shirts and cologne and majored in business and forestry and political science. They were respectable. Do any of those men think about that night, consider what they perpetrated on our bodies? And now, at 45, wonder if their actions might cause them trouble today? Do they know that when I go to the doctor, I experience terror and a flight-or-fight response that I hide behind a blank face?

I certainly have no way to hold them accountable. But I hope they are as tormented as I am numb.

I once tried to numb myself out of existence in the Pacific Ocean one November long ago. But my husband waded in and got me out, and warmed me up. That night is woven into my existence, with a few other nights, and seems to silently, even without my knowing, influence so, so many decisions. I hope the boiling volcanic rage comes to the surface and burns this sort of thing out of existence.

Mandy Greer is a Seattle-based multi-disciplinary artist who creates heightened narrative space through fiber-based installation, photography, performance, film and community-based action. This essay was originally published on Mandy Greer's personal Facebook page.

Seattle Story Project: First-person reflections published at KUOW.org. These are essays, stories told on stage, photos and zines. To submit a story — or note one that deserves more notice — contact Isolde Raftery at iraftery@kuow.org or 206-616-2035.