Buses in the age of Uber: Seattle commuters face transit challenges

Since Uber and Lyft came to cities, fewer people take the bus. Now, buses are fighting back, with Uber-like services of their own.

It’s 8 p.m. on Sunday, and Scott Naymik has just finished a shift waiting tables at the Fiddler’s Inn, in Seattle's Wedgwood neighborhood.

“I’m about to head home and head straight to bed so that I can get up at 6 in the morning and be ready to go to the homeless shelter tomorrow,” Naymik said.

The homeless shelter is Naymik’s second job. They have third job too – as a health coach.

Working three jobs doesn’t give Naymik a lot of extra time to commute. They would love to take a bus home. But Naymik lives about a mile west of the Fiddler’s Inn and most buses run north south.

“Public transit’s not an option," Naymik said. "Unless I’d be willing to bus all the way to the U-district and all the way back up.”

Naymik said that hair-pin shaped bus ride usually takes 90 minutes and cost about $3. In contrast, an Uber ride would take five minutes and cost about $5. Naymik keeps fares that low by buying bulk packages of Uber rides and using an Uber credit card to get rewards.

A recent study showed that many people who take Uber and Lyft would otherwise have taken a bus. In King County, ridership on transit has grown, contrary to the national trend, largely thanks to regional investments in light rail. But Metro wants to do even better. And one way is by thinking more like Uber.

For example, Uber wants to be about more than cars. Uber wants to recommend different solutions for different situations. That's why it offers bike rentals and is gradually adding bus information to its app, city-by-city.

Metro’s doing something similar. It doesn’t call itself a bus agency anymore. Now, it’s a mobility agency.

“Often times it will be the bus, but other times it could be an innovative mobility service, it could be van pooling, it could be walking or biking," said Casey Gifford, Metro senior planner.

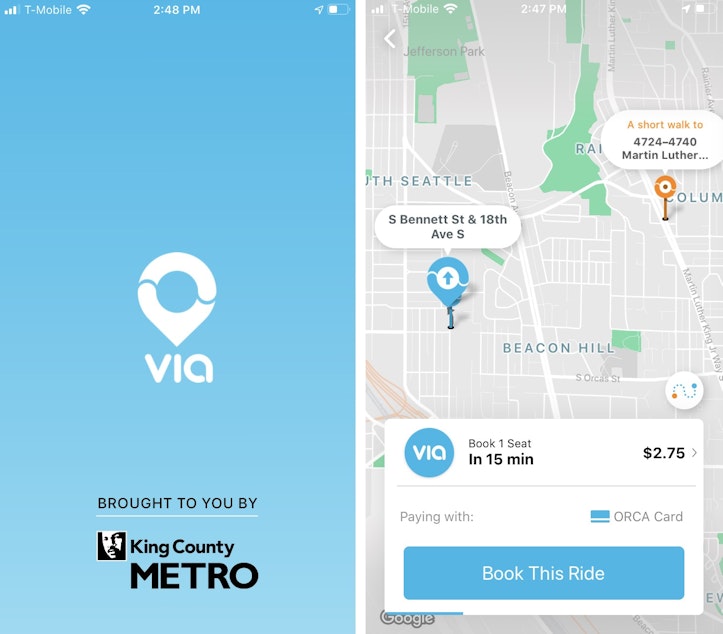

One thing Metro’s been experimenting with lately is Via To Transit.

“It does have similarities to Uber and Lyft in that customers can book a ride on demand,” using an app, Gifford said.

Then Via vans pick up people near their homes and take them to a nearby Link Light Rail station. Riders pay a standard bus fare, and get a transfer they can use on buses and light rail.

It’s still just a pilot project in south Seattle. But already, it’s given a quarter million rides.

The service is expensive for Metro to run. While commuters only pay a standard bus fare to ride, a single Via ride costs Metro $10, compared to an average bus ride that costs Metro around $5 per ride. But that's a bargain compared to the cost of operating some under-performing bus routes. So it could make sense, in places where buses run mostly empty.

Metro’s been cranking through other pilot projects, too. Metro’s Victoria Tobin said Uber and Lyft have opened people up to trying new things.

“That’s what we’re finding with all the pilots we’re running," she said. "People are not afraid to embrace technology. They actually love it.”

Steven Higashide is the author of Better Buses, Better Cities: How to Plan, Run, and Win the Fight for Effective Transit. He is also director of research for TransitCenter, a foundtation that researches the same topic. Higashide cautions people not to get too obsessed with copying Uber and Lyft. After all, he points out, Uber is a company that’s losing billions of dollars every year. (Uber argues that the rides app itself is profitable.)

Higashide said King County Metro seems to be approaching its Uber-inspired experiments reasonably.

“They’re not simply innovating for innovation’s sake," he said. "They’re willing to pull the plug on experiments that aren’t working.”

None of these experiments Metro’s doing at this time will help Scott Naymik -- the commuter we started this story with. That's because Naymik works three jobs and pretty weird hours.

Higashide says transit agencies tend to have a bias for people working one 9-to-5 job, “even though people who work second shift or third shift jobs often would benefit from high quality transit,” he said.

King County Metro wants to make sure it’s not leaving anyone out, especially low-income workers who can’t afford Uber or Lyft.

"Equity is at the forefront of our goals with this pilot," Metro Spokesperson Torie Rynning wrote in an email. "Therefore we don’t evaluate service purely on cost and ridership. We also look at how we are providing access to historically underserved areas with high percentages of low-income people, people of color, and people with limited English proficiency."

For now, Naymik is okay sticking with Uber.

“I’m grateful that we have technology that’s able to make transportation accessible,” they said.

And until something better comes along, Naymik will continue to milk Uber’s loyalty programs, trying to keep fares as low as possible.

In the end, Uber and Lyft may end up playing only a minor role disrupting commute patterns in north Seattle. When light rail comes to Northgate in 2021, Metro will no longer face as much pressure to carry commuters from north to south. When that happens, the agency will have new reason to run buses east-west. After Metro redraws the bus route map, Naymik could end up with frequent, convenient bus service after all.

We'll touch on light rail's impact in future stories.