Washington's floodwaters revived a Canadian lake wiped out 100 years ago

At the bottom of an old, dry lake bed are farms that supply British Columbia with a lot of its milk, butter, and cheese.

Recent flooding throughout the region could cost hundreds of millions of dollars while raising complex questions about whether Canada or the United States is responsible for the damage.

The Sumas Prairie spans the U.S.-Canada border. It’s shaped like a bathtub, with mountains on all sides. The bottom of the bathtub slopes down to Canada. And right about where the drain would be is Cynthia Dykman’s dairy farm.

“It was sort of like a … a big wave,” she said.

When the flooding started in November 2021, many of Dykman’s 800 milking cows were pregnant.

“Some of the cows – the calves were being born in the water. Because you can’t determine when a calf is being born, and there’s the water and we haven’t moved her yet and she’s birthing…”

Dykman has lost around 50 cows and calves, so far. And that number keeps growing.

“It’s awful. They’re bawling. And you can’t do anything," Dykman said. "And then you’re going to feed them and there’s another dead one, and another dead one .... because they got too cold.”

Dykman's insurance won’t cover what she lost in the flood because it’s considered an Act of God. But Dykman doesn’t see it that way. She says the United States has failed to manage the Nooksack River. After all, this is not the first time floodwaters flowing out of the U.S. have covered her farm.

“We don’t have the power to hold back the Nooksack here, not at all," she said. "We can deal with our own water, but when it comes to the Nooksack headed this way, we can’t deal with that.”

One official picking up that argument is Mike DeJong. He’s a politician who represents Dykman’s area in the Canadian equivalent of the state legislature.

“The real source of the issue is the Nooksack river itself, which normally does not flow through Canada," he said.

There’s an international commission that resolves cross-border water disputes, between the U.S. and Canada. DeJong said he wants them to get involved.

"We may well see some claims for compensation,” he said.

Sponsored

In other words, he said the U.S. may have to pay.

“When something happens on your property or something escapes your property and does damage to your neighbor’s property, there is an obligation there," DeJong said.

DeJong said the U.S. should raise the levies along the Nooksack and dredge or deepen the river, so it can hold more water. It’s a popular idea with rural residents on both sides of the border. But not all Canadians are ready to support that conclusion.

“I’ve heard the tone of the sense of blame of how dare water come from Washington into Canada. I think that’s ridiculous, personally," said Camille Coray, executive director of the Great Blue Heron Reserve near Chilliwack B.C., which also flooded.

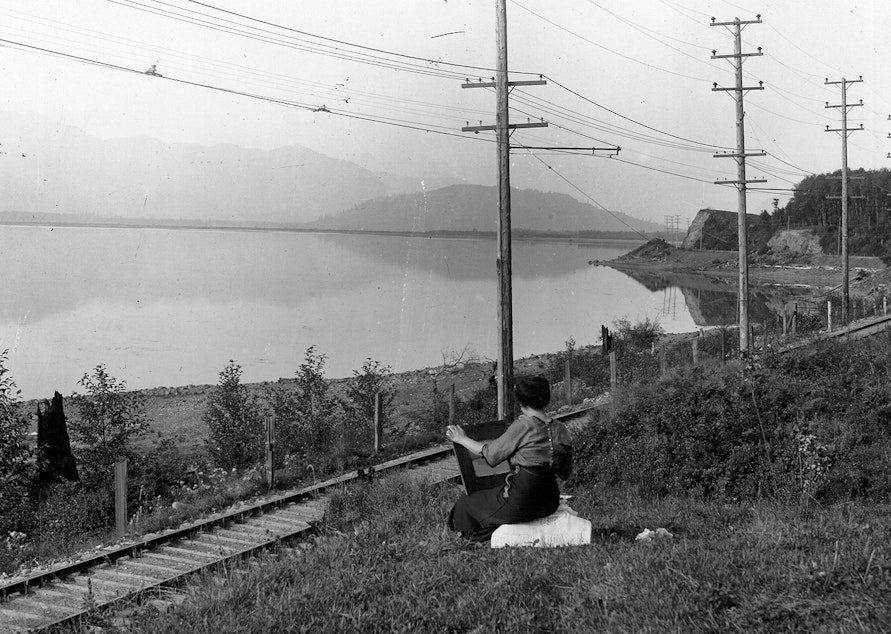

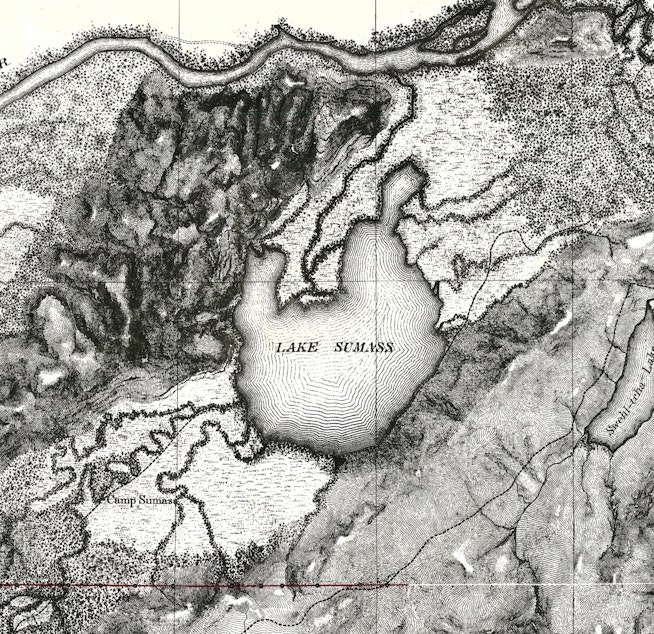

She pointed out that this area was naturally underwater just over a hundred years ago. In fact, it was a shallow lake, called Lake Sumas, surrounded by wetlands.

Sponsored

From time to time, the flooding Nooksack River and other US rivers would feed it, along with Canadian sources. It expanded and contracted over time, occasionally reaching south of the border into Whatcom county.

In order to claim the farmland, the Canadians installed mechanical pumps. And those pumps have been running almost non-stop for a century, keeping the land dry.

“That’s just kind of crazy," Coray said. "Of course the lake wants to come back."

“It’s a bit disingenuous to suggest that the Americans are somehow dropping the ball and punting the problem to us," said Canadian historian Chad Reimer.

Sponsored

Reimer wrote a book about Lake Sumas called Before We Lost the Lake: A Natural and Human History of Sumas Valley.

“The flooding is not the problem. Flooding is natural, especially here. The problem occurs when we put things in its way,” he said.

Reimer asks whether cows and chickens and people should be kept on this land, because it's not truly land.

“Sumas Lake did not 'go away' in the sense that the environmental and natural forces that created Sumas Lake are still there," he said. "And we are just seeing nature come back."

The loss of Sumas Lake took away one place the rivers could naturally overflow into.

Decisions people make after a flood can have trickle down effects, hurting wildlife like salmon. That’s according to George Swanaset Jr, with the Nooksack Indian Tribe.

“We’re always fixing everyone else’s mistakes,” he said, noting that local tribes are often stuck trying to restore salmon populations that were harmed from past flood responses.

Whatever the solution this time, it’ll be costly.

Ted Perkins works for FEMA on the US side. He said figuring this out is really complicated. And so, he likes to start with a simple question.

“Where does the water want to go?" he asked. "And then, try to find the areas that are easier to manage, essentially.”

It used to be, the easiest thing to do was to let water come and go as it pleases, and stay out of its way. But now, with so many farms and buildings on that land, it’s gotten a lot trickier.