Washington Indigenous families still living with the 'very deliberate effort to wipe us out'

The U.S. Interior Department has set out to document abusive boarding schools that once targeted Indigenous tribes, their cultures and their children.

A first-of-its-kind report from the agency's Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative puts the extent of that abuse in black and white.

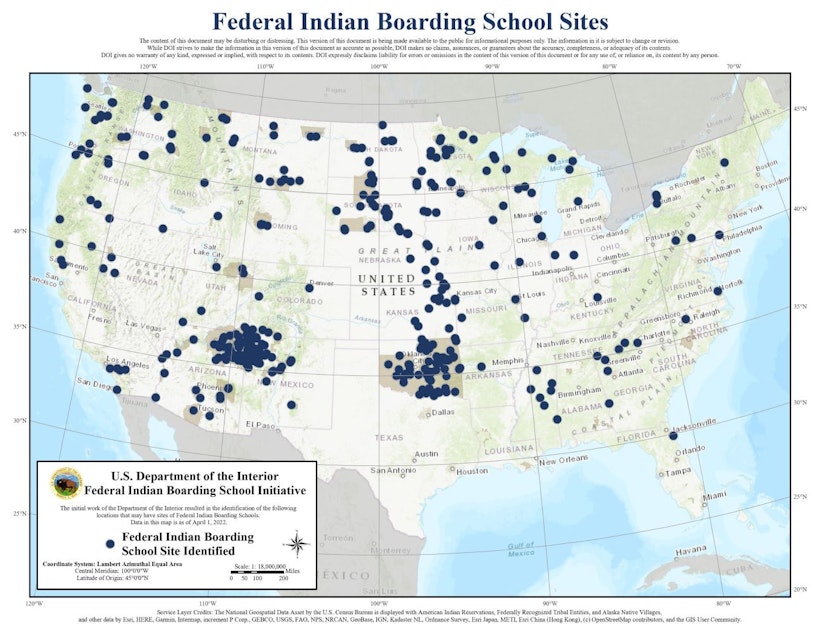

Researchers found evidence of more than 400 schools across the United States and at least 50 burial sites where children were left in unmarked or poorly maintained graves. The investigation has uncovered more than 500 deaths.

And they're still counting.

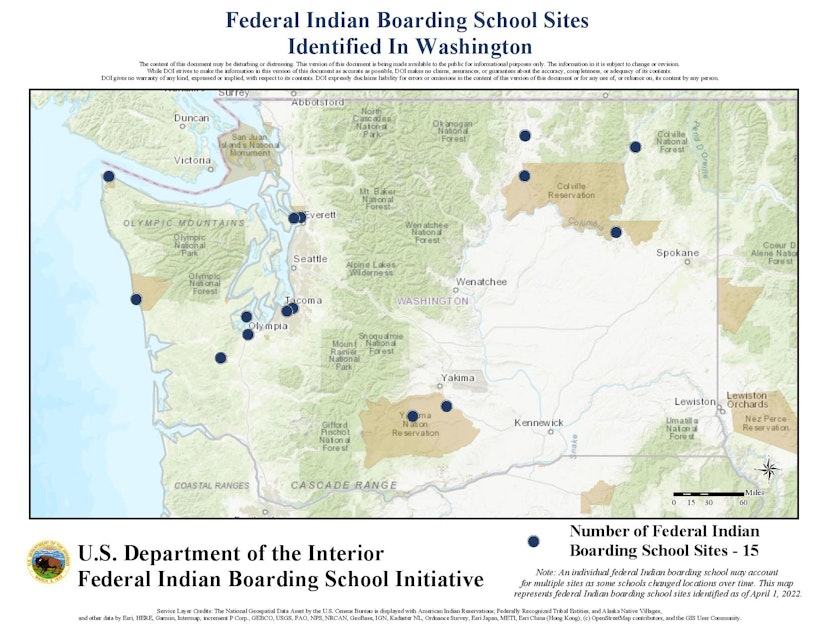

At least 15 of the schools were operated in Washington state. Another nine were in Oregon.

Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report

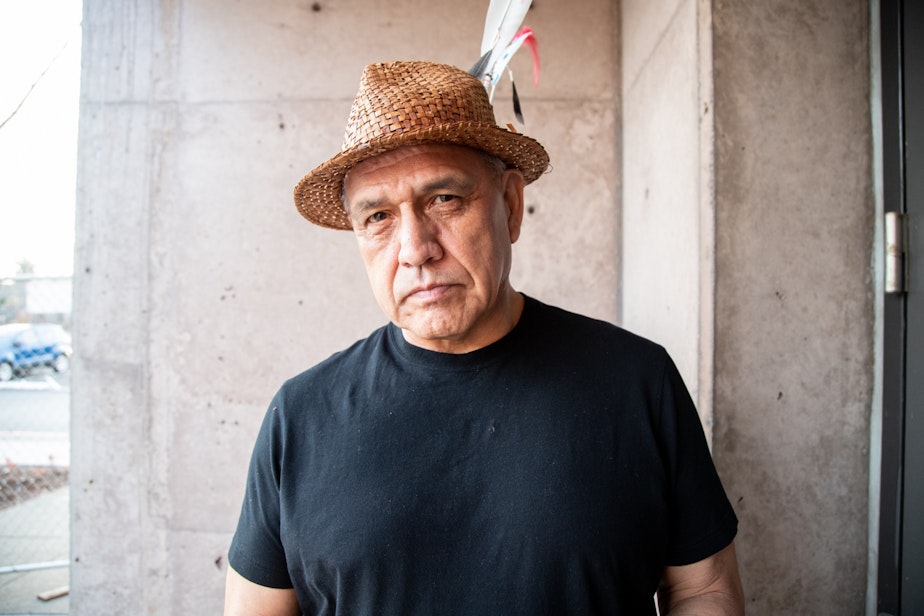

Darrell Hillaire is a member of the Lummi Nation, a leader and teacher who uses the tradition of storytelling and song to educate the world about his people and others.

Years ago, Hillaire’s parents were sent to one of the largest boarding schools in the country, the Chemawa Indian Training School in Salem, Oregon.

Hillaire said his father only started talking about the experience late in life, just a few years before he died. He talked about the deep loneliness he felt at the school, away from his family and culture.

"These things are not taught in our history books, in our school systems. But it's also not talked about by the elders that have had these experiences, because it's so hurtful," Hillaire said. "That was a part of the training they got in boarding school: to not practice your language, not practice your culture, sit down and shut up."

Now, though, that history is being revealed. That's important, Hillaire says, to ensure we "never repeat that ever again, here or anywhere else in the world."

"It's the foundation of our country, what happened to our people," he said. "People need to know how that foundation was built."

A new era of accountability

The professed goal of boarding schools for Indigenous children was to assimilate them into white society, separating them from their native tongues, cultures and families.

The children were sent to highly militarized and often abusive schools, which were operated with the support of the U.S. government. Some of the schools were run by Catholic, Protestant and other churches, according to the report. The government backed their efforts to "civilize" Native Americans.

The report released earlier this month is just the first volume of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative's work. The second volume is expected to uncover additional burial sites and detail financial investments the U.S. government made in these schools.

This traumatic history has been known for years, though, particularly among the Indigenous communities that have felt the impact of boarding schoolsde for generations.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland acknowledges the lasting effects.

"The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies — including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old — are heartbreaking and undeniable," Haaland said in a statement.

Haaland speaks from a shared community experience.

As a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, Haaland became the first Native American to lead the U.S. Department of Interior. She was nominated for the position by President Joe Biden. Haaland launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in June 2021.

The effort came in the wake of a jolting discovery in Canada: the discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children at the Kamloops Residential School in May 2021.

The National Congress of American Indians, or NCAI, credits the discovery for bolstering efforts to investigate similar boarding schools in the U.S.

In a statement, NCAI First Vice President Mark Macarro said this first report is progress toward justice and healing.

“The horrific abuse, neglect, starvation and forced assimilation of Native children combined with the destruction of our tribal languages cannot be ignored," Macarro said. "While the report findings mark a new era of accountability by the federal government, there is still much truth, justice and reconciliation needed in our communities.”

'Taking our rightful place'

Darrell Hillaire is clear: The effort to assimilate Indigenous children was an attempted "annihilation" of native peoples. But because they did not talk about what happened in those schools, that context was largely missing.

"I really didn't understand... what we're healing from — the alcohol and the drug abuse and the broken families and all of that," Hillaire said. "It does trace back to the boarding school experience, traces back to the introduction of alcohol by the outsiders in our communities, traces back to the child sex abuse that came through the churches, traces back to not being allowed to fish or hunt or gather."

Without that understanding, Hillaire said the grief stays inside, creeping up out of nowhere when stories like the one about the Kamloops Residential School in Canada are told.

"All these things added up to a very deliberate effort by this country, this government and the captains of industry to wipe us out," he said.

But in the grand scheme, they failed.

"We're still here. We're emerging and we're healing and we're taking our rightful place [as leaders]," Hillaire said. "We're setting examples for how to treat the environment and live with Mother Nature and live with each other."

Today, the federal government's attempt to assimilate Native Americans and erase their practices is ironic to Hillaire.

"We're working with [officials] today to save salmon and free rivers," he said. "We are raising the kind of energy needed to respond to what Mother Nature is telling us."

Still, he said more must be done to bring this trauma to the surface and allow those affected to heal.

"These are children we're talking about," Hillaire said. "We need to teach in our school systems, in this country, the truth about the genocide of our people."

'A good manner of being'

Hillaire continues his family's legacy of Lummi storytelling.

In the 1930s, his great-grandfather Frank Hillaire formed a Lummi dance troupe called the Children of the Setting Sun.

Today, Darrell Hillaire is the founder and executive director of Children of the Setting Sun Productions, a multimedia arts company that uses traditional and modern art forms to keep their culture alive.

Asked what the group is currently working on, Hillaire chuckles: "Well, you'll have to come and spend some time with us."

In other words, the organization is busy and much of what they do is best experienced in person.

Initiatives like the Salmon People Project are multi-faceted, including a feature film that's showcased in the Northwest Coast Hall of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

The Salmon People Project is currently Children of the Setting Sun's keystone, an art and research project that frames salmon as "the miner's canary of the Salish Sea."

Hillaire said the salmon are the key indicator for maintaining the balance of life in their community.

But the project means even more than that.

It speaks to a Lummi principle Hillaire lives by. It translates to "a good manner of being."

"I carry that with me when I watch the people gather," he said. "I see the people trying to heal and trying to put ideas together to make this place a better world."