The secret diaries my grandma snuck out of a Communist prison in Vietnam

My grandfather, Thanh Ta, was a South Vietnamese soldier during the Vietnam War. After the war ended, the Communist government imprisoned him in an re-education camp.

As a way to connect with his family, he secretly wrote letters, poems and stories.

I'm now working to understand my family's past, through these documents.

When I went to interview my grandparents, their kitchen table was covered with dozens of letters and four journals filled with stories and poems.

When I was in middle school, my ông nội, my grandfather, told me he had written all of these things for his family.

Sponsored

When he was taken, he left behind his two young sons and my grandmother, who never knew when he was going to come back.

“I cried a lot,” my grandmother told me in Vietnamese, “day after day. Another week passed, and another week passed. I never saw your grandpa come home.”

My ông nội was first put in a jail in South Vietnam. Then, he was transferred to one in the Northern region, thousands of miles away from home.

But my grandma kept visiting him. She bought train tickets on the black market and took her six- and nine-year-old sons.

She smuggled in paper for him to continue writing.

Sponsored

“I had to hide them very carefully inside the clothes,” she said. “I would sew a pocket in them to hide the journals. It was very difficult to hide the papers inside those packages of clothing.”

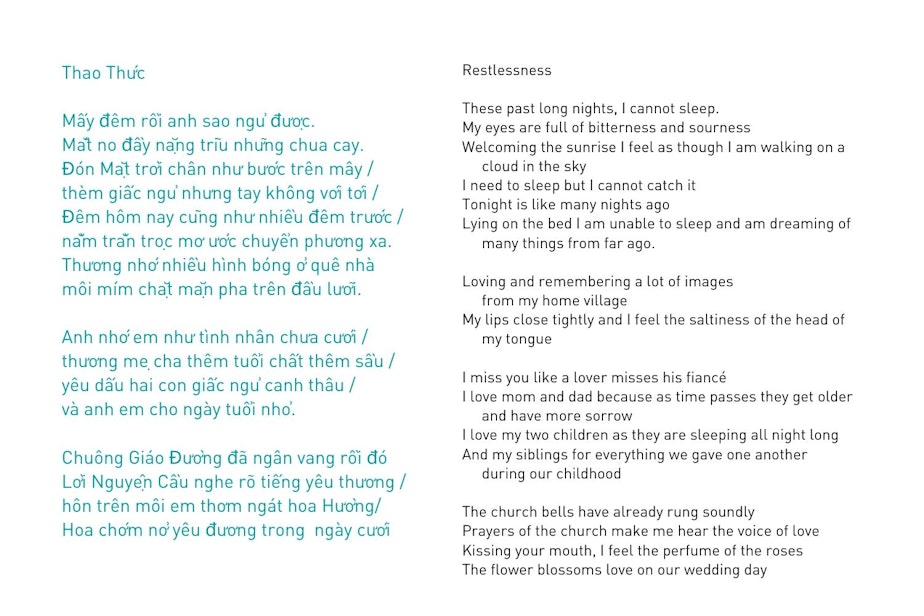

My grandpa would fill up the journals with stories about his childhood memories, his hometown and his family. Then he would sneak them out to her one by one so she could read the stories to their sons.

I asked him what would happened if he had been caught writing.

“Thì nó, họ không có cho phép mình viết,” my grandpa said. “They didn’t allow me to write. If they saw me writing, they would have confiscated them. They would have burned them. They would have ripped them all.”

But ông nội never stopped. He told me he was scared of dying in the re-education camps, so he was determined to write down as much of his life as he could.

Sponsored

“I did this because I wanted my loved ones at home, especially your grandma and my sons, to know that while I am far away, my soul and heart and love are always with my family.”

My grandpa’s writings have been preserved for generations. They are just one piece of the big story of Vietnamese immigrants who came to the United States after the war.

I want to continue to preserve them as well.

Documents like my grandfather's are housed in the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience.

I went there to talk to Jessica Rubenacker, the exhibit director of the museum. I showed her my ông nội's letters and asked how they could contribute to the story of our Vietnamese community.

Sponsored

"We're collecting things just like this," Rubenacker told me. She said they use people's personal stories to bring the museum's artifacts to life.

Ông nội would love it if his stories could be preserved.

"If they could be translated in English, the better," my grandfather said, "so researchers can read my journals and understand the society and history of Vietnam, and what the Vietnam War was like."

Even if his writings don't end up in a museum, they are still a record of the incredible risks he and my grandma took.

For that, they are my heroes.

Sponsored

This story was created in KUOW's RadioActive Intro to Journalism Workshop for 15- to 18-year-olds, with production support from Sonya Harris. Edited by Marcie Sillman. Voice-overs by Ann Van and Kevin Nguyen.

Find RadioActive on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and on the RadioActive podcast.

Support for KUOW's RadioActive comes from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center.