A device to 'cleanse' the brain and enhance sleep: UW researchers have started human trials

1 min

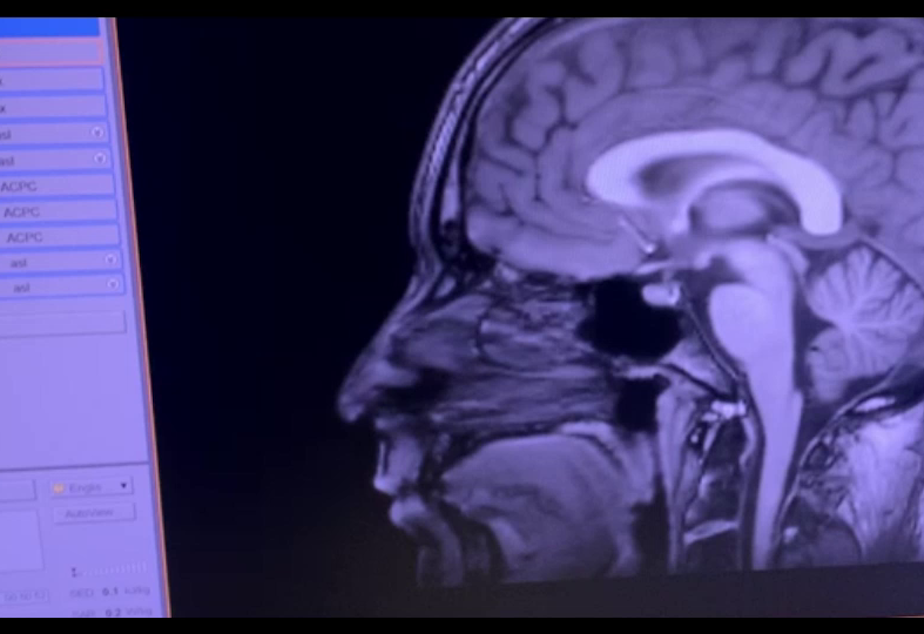

A University of Washington research assistant undergoes an MRI as part of a study on a sleepband device that would "cleanse" the brain to enhance sleep for the chronically sleep deprived, such as soldiers and mothers.

1 min

A University of Washington research assistant undergoes an MRI as part of a study on a sleepband device that would "cleanse" the brain to enhance sleep for the chronically sleep deprived, such as soldiers and mothers.

At the University of Washington Medical Center, radiologist Dr. Swati Rane Levendovszky watches brain pictures. The brain belongs to her research assistant Cole, who is lying in the MRI scanner in the next room.

Levendovszky designed this MRI scan to teach us more about how brains clean themselves during sleep, to better understand the glymphatic system. As you sleep, your brain relaxes and lets extra cerebral spinal fluid wash through it, flushing away the cellular waste that accumulates throughout the day. If you don’t sleep enough, you don’t just feel foggy; you’re at higher risk for depression, headaches, and possibly dementia.

Researchers want to see if they can enhance the glymphatic process with an electronic headband that would stimulate your brain in just the right way. The hope is that we could get better brain cleaning with less sleep, or even get some of that benefit while we’re awake.

Dr. Jeffrey Iliff, a neurologist at the University of Washington, says the trials are being paid for by the U.S. Defense Department because so many service members have trouble sleeping.

“Whether they’re pilots flying very long missions, people on deployment, where you get four hours of sleep a night for three months or nine months at a time, or Special Forces operators on a 72-hour mission where sleeping really isn't possible, or it's highly, highly restricted, and yet you have to do these very complex, very important and very dangerous tasks.”

I asked Dr. Iliff whether he has ethical qualms about possibly helping the Pentagon turn service members into super, non-sleeping fighting machines.

Sponsored

“I don't think that that's the goal here at all,” he said. “The reality of deployed life is, it’s very tough, it's very austere, and it's very difficult and dangerous. And so given that reality, how can we optimize the health of these people both when they're carrying out their operations, but also later in life?”

Iliff said he’s not looking to reduce the role of sleep in our lives. We need sleep, not just for brain-cleaning, but because it prunes our neural connections and helps our brain consolidate memories. If you can go to bed, Iliff said, do it — at the same time, every night. Limit caffeine. If you have insomnia, try talk therapy. However, some people are still not able to sleep well.

“People who are shift workers, they just can't get normal sleep,” said Illiff. “People who have had a head injury, people who have had strokes, people who are undergoing treatment for cancer, people who are aging — these are people who have chronic sleep problems and there's really not much we can do about it.

"The question is, for those people, do we have something for them, whether it’s a behavioral therapy, a drug, or a device.”

There are also questions of equity. Would this headband or drug be so expensive that only the rich get an enhanced brain cleaning? Dr. Rane Levendovszky says the ultimate goal is to help people from all walks of life.

Sponsored

“As a woman from India, somebody who's working with a five-year-old, and has had many sleep-deprived nights, I have special interest in understanding what is really happening with lack of sleep and can that be improved even in mothers," Levendovszky says, "career women who have to juggle personal life and their jobs. That has been a big issue, especially in the pandemic."

The trials will be conducted among 90 people at UW School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Oregon’s Health & Science University and Brain Electrophysiology Laboratory.

At this stage of the work, researchers need their subjects to be similarly young and healthy. But eventually, both UW researchers said, we need to know more about how sleep works in people of different ages, health conditions, social status, abilities, genders, races and ethnicities.