'Something has to change:' These architecture students are challenging Seattle's housing norms

The City of Seattle expects to have 1 million residents by the year 2044. That’s about one-third more people than Seattle has right now.

We’re having trouble housing the people here now. So where are we going to put all the new people?

Some University of Washington architecture students are looking at new ways to add more housing to existing neighborhoods — without ticking off the neighbors.

Their timing is perfect, as Seattle and other cities are currently updating their comprehensive plans, which lay out where and how they’ll grow over the next 20 years.

In the skylit atrium of Gould Hall, this year’s crop of architecture graduate students showed off their final projects.

Some architecture students dream of designing fantastic buildings that will inspire visitors from around the world. But many of the students presenting their ideas during their last week of school had a more pragmatic goal: Just to find a way to live in this expensive city.

“And it’s funny because I live in a one bedroom and I share a bed with my roommate,” said student Michelle Loyola, adding that this is not her ideal scenario. “And we literally split the rent like that. So it just means that something has to change.”

What has to change is the housing market. For her project, she designed a big home in Seattle’s fancy Seward Park neighborhood, where there are a lot of mansions with waterfront views.

What makes her house different is that there are actually eight two-bedroom homes, hidden inside. Splitting the high cost of land among eight families brings the cost way down.

Sponsored

“To buy a unit, it would be $690,000,” she explained. That’s less than the average home price in Seattle, which is currently just under $1 million dollars. And it’s far less than the average in Seward Park, which Loyola estimates is closer to $3 million.

In Loyola’s project, residents would share outdoor space, and a few common areas. It’s called co-housing. She said a visit to Denmark and her current experience have both prepared her for that lifestyle.

“You don’t need 1,600 square feet for a single family," Loyola said. "I’m not saying that everyone should share one bed with their roommate, but…I think we’ve been living with a lot of excess.”

Tradeoffs: What are we willing to give up, to achieve affordability?

Sponsored

Almost every one of the students here has a story about experiencing Seattle's unaffordability.

“We make Seattle income, but we still can’t afford the houses in Seattle. We have to live all the way in Bothell or Federal Way,” said student Lara Tedrow.

“In 5 years, when I want to buy my own house. I don’t think it’s going to be possible to do in Seattle,” said student Carrie Kamakaala.

In response to these challenges, each project in this presentation demonstrates a different solution to this problem — a different a way we could achieve a measure of free market affordability by relaxing some zoning law or another.

Sponsored

Loyola’s project, for example, gives up the idea of having a front yard and a backyard. Instead, outdoor spaces become courtyards between buildings, where residents can gather.

This class is all about tradeoffs, instructor Rick Mohler said. He said solving the region’s housing crisis will require compromise. The task before us is to collectively examine which compromises we’re willing to make.

Later this summer, other students will further analyze the designs to learn how much more housing we could build for each of these sacrifices. The idea is to create us a shopping list so we can say, “well, if we’re going to get that much housing by giving up open space that runs along the side property line so we can build rowhouses, maybe it’s worth it,” or “giving up backyards is too much sacrifice for too little gain.”

The Bao House: A case study

Student Miggi Wu, who grew up in a three-family, multigenerational household in Renton, wants to develop a property that can bring her family together. Many of her relatives have fled Seattle for Atlanta, where homes are less expensive.

Sponsored

In the backyard behind her mother’s house in Seattle, Wu proposes building six more homes: Two two-bedroom houses and four studios, which would sell for $608,000 and $131,000 respectively (the studios would be sold with the homes). Her mother could run her business selling steamed buns, which is why called her project the “Bao House,” a pun on the name of a famous architecture school created by Walter Gropius.

As part of her presentation, Wu drew a cartoon panel, with people of different generations calling out to each other — a kid asking for a ride to school, an aunt answering from a balcony saying she’s busy, a grandparent handing children a bao to eat as they rush to catch the bus, and a neighbor asking when they can come by and pick up some bao.

Achieving this vision would require the relaxation of rear setback requirements, and an increase in the percentage of a property that may be covered by buildings, along with zoning changes allowing her mother to run her bao business from home.

Sponsored

Less expensive "missing middle" housing

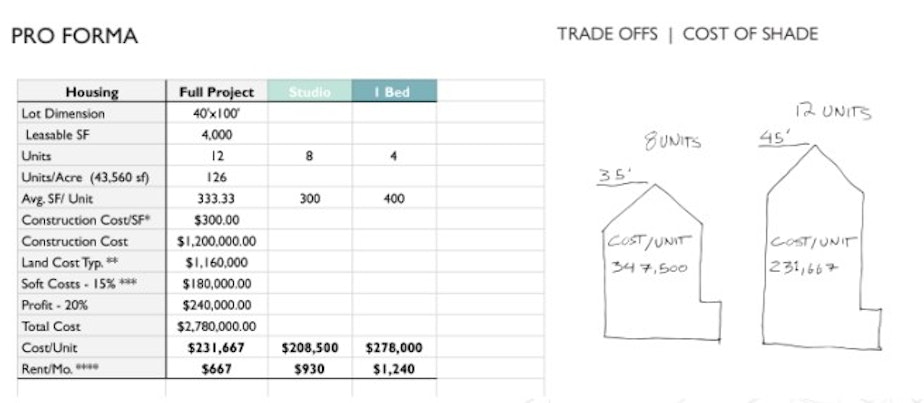

Each of the homes the students designed went through a cost analysis process, which took into account the land costs, construction costs, and demolition costs (where applicable) at each site. Some of the homes turned out to be astonishingly affordable. One project includes studio apartments you can buy for $129,000 or rent for $722 per month.

Another student’s project ran the numbers with and without relaxing the rules. In his case, relaxing the rules knocked $100,000 off the price of a home. That’s lower savings than some of these projects, showing that not all properties will perform at the same rate.

Fitting density into the neighborhood

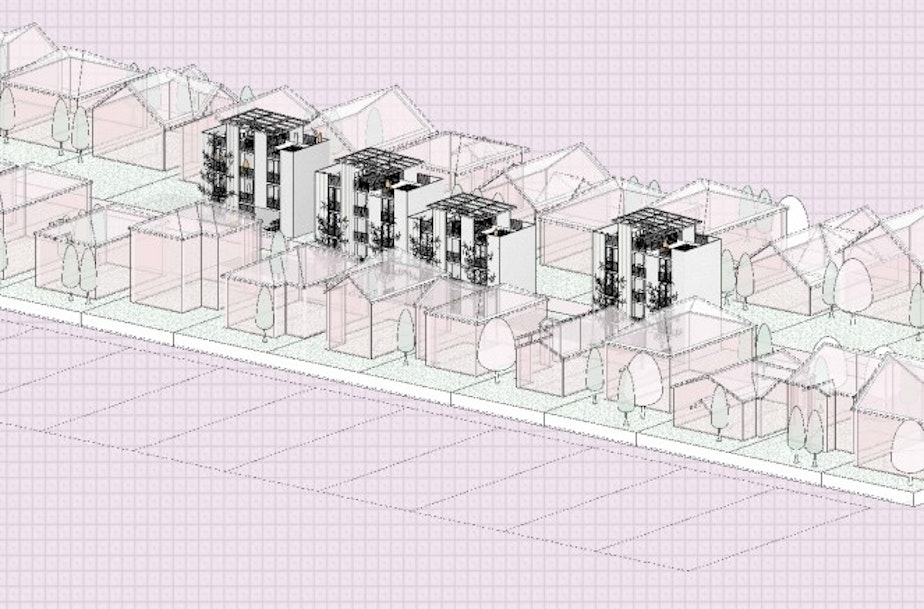

The way they achieve this affordability is through density. But they also know that many single-family homeowners oppose density like this in their neighborhoods.

That’s one reason many of these students designed what are essentially condo buildings that look like single-family homes. It’s a form of camouflage.

“The idea of doing that was to blend more into the neighborhood and...presumably the response from the neighbors would be a little bit better” explained student Azita Footohi.

Lara Tedrow’s project features a single front entrance, rather than the multiple entrances seen on townhome projects.

“It's not trying to disguise itself — it's more to defer to what's around it. And to say, ‘Who cares if there are eight families on this lot, it looks like every other lot.’”

Another way students tried to make their big buildings fit in is by keeping the existing home and building a much bigger apartment or condo building in the back yard, kind of like a backyard cottage on steroids.

Student Addison Peabody said it might seem strange, at first, until you understand the reason behind it.

“We’re not just doing it because we feel like it,” he explained. He said he wanted to keep the existing home to prevent displacement. Madison Park (where his project site is located) “has a large number of retirees, or folks who are going to become retirement age in the coming years. So providing an opportunity for people to age in place, to live where they would like to, while opportunities for new homeowners…that was really the motivation for preserving the existing housing while selling off the rear yard.”

To get these homes built will take a change to current zoning laws, like relaxing height restrictions and front and backyard setback requirements. But it’s not just the neighbors who they have to convince. They have to convince politicians and public officials, too.

Good timing

Right now, Seattle is updating its comprehensive plan, which determines where and how the city will grow over the next 20 years. The state requires cities to update these plans every 10 years (previously every eight years).

Seattle’s past comprehensive plans have set modest goals for housing production — for example, to build 70,000 homes between 2015 and 2035. And while technically we’re on pace to meet that goal, it’s clear city officials dramatically underestimated how many people would move here, attracted by Seattle’s robust, tech-fueled economy.

The result of this failure has been rising housing costs and homelessness, with higher income residents displacing those who don’t earn enough money to compete in the housing market.

The Office of Planning and Community Development estimates Seattle has about 375,000 homes, according to spokesperson Jason Kelly. He said we need to build 152,000 market rate homes by 2045 — that’s 40% more homes than we have now — in order to house everybody and make up for ground we’ve lost by building too slowly. That’s in addition to subsidized affordable housing we need to build for people on lower incomes than the housing market will serve on its own.

Experts say that kind of density will be difficult to achieve without “spreading the peanut butter” of density across more of the city, including neighborhoods currently dominated by single family homes.

The push for “missing middle” housing is a response to this need. A statewide bill that would have allowed six-plexes on single family lots failed in the last legislative session, but comprehensive plan updates, also required by state law, give cities a reason to revisit some missing middle prototypes, including new ones presented by these students.

Seattle is in the room

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell has committed to exploring new ways to add housing in Seattle. His deputies are in this very room, reviewing these student projects, absorbing their ideas.

One of those reviewers is Rico Quirindongo, who used to be one of these students. Today, he’s the acting head of Seattle's Office of Planning and Community Development.

“I think that some of these plans are actually really great," Quirindongo said. "I will admit that some of them are at a scale that’s too much…and so, that’s the balance we have to look at. And I want to be very sensitive to that.”

Quirindongo added the students are right that Seattle must increase density.

“That is real, and we are going to have to do that in Seattle.”

But he added that getting it done requires lots of outreach work too, to make sure everyone feels heard and understood, especially Black, Latino, and other BIPOC residents who sometimes aren’t asked if they want development in their neighborhoods.

After this presentation, these students will go out in the real world. One of the class’s teachers, architect Matt Hutchins, gave them a pep talk on their way out the door.

“I think the big takeaway (is) now all of you are housing activists. All of you are advocates and you’re all experts. And you can now start to apply pressure, to start making the places that you want to live in this city.”

These graduating students will be among the voices you’ll hear testifying at city council meetings over the next three years, as the city updates its comprehensive plan and charts out its future.

Correction Notes:

- Seattle's current comprehensive plan required the creation of 70,000 homes by 2035, not 2025.