Climate choice 2020: Trump’s 'wrecking ball' vs. Biden’s mixed record

1 of 4Mt. Anderson, the headwaters of the Quinault River in Olympic National Park, photographed 84 years--and one glacier--apart.

1 of 4Mt. Anderson, the headwaters of the Quinault River in Olympic National Park, photographed 84 years--and one glacier--apart.T

hree days in from the trailhead, we weren’t sure what to do when the wildfire smoke thickened. Hiking deeper into the Olympic wilderness, toward the apparent source of the smoke, seemed a bad idea.

The air, dirty enough to turn the sun a sickly pale orange, was unhealthy to breathe, let alone exercise in.

Worse, beyond the reach of the internet, we didn’t know whether this smoke was billowing up from California or from some nearby blaze.

We donned our smoke masks, set up our tent by a grove of ancient mountain hemlocks and mostly hunkered down.

A short walk to a mountain stream offered some relief: Spray kicked up by the tumbling waters seemed to knock the fine particles of soot out of the air, at least within a few feet of the creek.

A day later, as we were beating a retreat to our car, the smoke lifted just enough that we felt emboldened to explore the high country of Olympic National Park instead of racing back to civilization.

Our new destination, a short detour off our retreat route, was the Anderson Glacier, a river of ice at the mile-high headwaters of the Quinault River.

But where our 2016 topo map said a nearly mile-long glacier awaited us, the ice was gone.

In its place, an ice-gouged landscape of the sort glaciers leave behind: boulders strewn like confetti; clusters of wildflowers hugging the mostly bare earth; scattered patches of snow up high and an unnamed, milky green lake below.

Drag the slider to see the Anderson Glacier in Olympic National Park disappear:

Glaciers and icecaps around the world have retreated dramatically as humanity’s pollution has warmed the climate.

Many have just disappeared.

The Olympic Mountains lost 82 glaciers from 1982 to 2009, according to the National Park Service, as more rain and less snow fell on the rivers of ice.

The Anderson Glacier waned slowly until the 1980s.

It was essentially gone by 2015.

Quinault Indian Nation president Fawn Sharp took an aerial tour of the headwaters of her tribe’s namesake river in 2018.

“To come right up to a mountain and expect to see a glacier and see nothing… I can tell you this: The helicopter flight back was somber,” Sharp said. “We were all without words. What can you say?”

Sharp knows better than most why the world’s melting ice matters.

“Quinault Nation is having to relocate our village to higher ground because of sea level rise,” Sharp told a climate summit organized by the Washington State Office of the Insurance Commissioner in October.

“Here at the Quinault Nation, I have seen the impacts of climate change firsthand,” Sharp said.

The Quinaults have begun construction on a new village, just inland from the main village of Taholah and from the encroaching ocean.

A $15 million building for senior services and child care is nearing completion, but most of the $250 million project to relocate a village awaits funding.

A separate project to relocate the smaller village of Queets, at the reservation’s northern edge, is in the planning stage.

The rising sea is just one way a hotter world is already hitting the Quinault reservation.

With a warming ocean and without a big glacier to keep the Quinault River flowing cold and deep year-round, the salmon at the heart of Quinault culture have been dwindling.

“We’ve had to close our fishery three years in a row,” Sharp said. In addition to Chinook, chum and coho salmon, the Quinault River is home to a unique and fatty variety of sockeye salmon known as blueback sockeye.

“We could be the generation that sees the last blueback salmon return to the mighty Quinault. It’s, it’s unthinkable,” Sharp said.

And as people up and down the West Coast experienced, wildfire smoke made it dangerous to breathe on the reservation this summer.

“It was the probably the worst I’ve ever experienced in my life,” Quinault Nation vice president Tyson Johnston said.

“Real lives are being impacted by this,” he said. “We have a lot of folks with preexisting conditions.”

Johnston said a wildfire even burned on the reservation, a rarity on Washington’s soggy rainforest coast. The fire traveled underground, through trees’ root systems.

“We’ve not had a major fire in our area in a long time,” he said.

This is the West Coast’s worst year for wildfire on record, as hotter, drier landscapes burn more easily.

In your face, in your lungs

These sorts of in-your-face, in-your-lungs impacts have pushed the long-simmering climate crisis to the top of the agenda for many voters nationwide.

A national poll by NPR, PBS and Marist College in September found that climate change was the top concern for Democratic voters.

For Republicans, the economy and abortion were the top issues, with just 1% of Republican voters citing climate change as their top concern.

Scientists say our rapidly heating climate is the biggest threat facing humanity.

President Donald Trump doesn’t see it that way.

“I don’t think science knows, actually,” he said while being briefed in California on the state’s extreme wildfires.

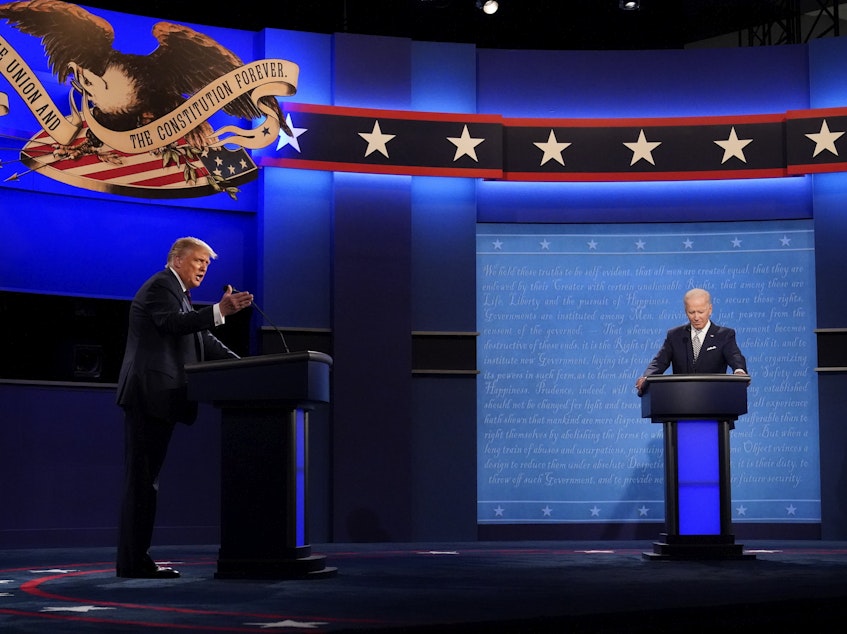

The political differences between Trump and his challenger, former vice president Joe Biden, are vast. Nowhere is that more true than on climate change.

Trump’s statements on climate change have been all over the map, from calling it a hoax to bragging, incorrectly, about the nation’s record on reducing heat-trapping carbon emissions.

“We have now the lowest carbon, if you look at our numbers, we are doing phenomenally,” Trump said during the Sept. 29 debate with Biden.

After declining slowly for about a decade, U.S. carbon emissions have flattened during the Trump administration.

That’s left America falling behind on the pollution reductions promised under the Paris Climate accord.

Trump calls that nonbinding treaty, signed by every nation on earth, “a disaster from our standpoint.”

Trump’s climate policies have been more consistent than his rhetoric.

This White House has systematically favored the coal, oil and gas industries and derailed federal action to protect the climate.

Biden calls climate change an existential threat and Trump a “climate arsonist.”

“We spend billions of dollars on floods, hurricanes, rising seas,” Biden said at the presidential debate. “We’re in real trouble—because of global warming.”

Biden is now proposing a $2 trillion plan of clean-energy investments to boost the economy and eliminate pollution from power plants in the next 15 years.

“Nobody’s going to build another coal-fired plant in America. No one’s going to build another oil-fired plant in America," Biden said. "They’ll move to renewable energy.”

But Biden has supported both pro- and anti-climate policies. He currently supports fracking for natural gas, a super-potent greenhouse gas.

Biden, of course, was vice president during the Obama administration, which pushed an “all of the above” energy strategy, promoting both clean and dirty sources of energy.

The Obama strategy boosted clean power plants. It also opened up the Arctic Ocean to oil drilling.

North Seattle College atmospheric chemist Heather Price, who calls herself a “climate voter,” is not a fan of Biden’s stance on fracking.

“We need to shift away from natural gas as quickly as we can,” Price said.

Still, Price said she’s voting for Biden.

If he wins, she said, activists would still have to push him to do the right thing.

“We have, essentially, two choices on our ballot when it comes to President, and one of them can be moved,” Price said. “One of them will listen to science, and the other one is a climate wrecking ball.”

A small number of conservative activists are trying to interest the Republican Party in tackling the world’s climate crisis.

It’s been an uphill battle, with many party leaders openly dismissive of the topic and Republican talking points including feigning ignorance to avoid discussing it.

“I’m certainly not a scientist,” Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett said in her Senate confirmation hearing in response to a question about climate change. “I mean, I’ve read things on climate change. I would not say I have firm views on it.”

The Republican candidates for Washington governor and public lands commissioner have both expressed their doubts on the well-established reality of human-caused climate change.

“It’s still a controversial subject, whether we actually have climate change,” said Republican fisheries biologist Sue Kuehl Pederson, who is challenging incumbent Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz.

“I don’t worry about cause and effect, because it doesn’t matter at this point,” she said.

Franz said she has expanded wind, solar and biomass power on state lands and developed a statewide plan to make public lands more resilient to climate change.

Republican gubernatorial candidate and Republic, Washington, police chief Loren Culp said he doesn’t deny that the climate changes. He also said, on a recent Facebook Live chat, that he’s old enough to remember the “big scare about global cooling” in the 1970s.

“It was on the national news: ‘Global cooling! We’re all going to freeze to death!’” Culp said. “Then it was ‘Global warming! We’re all going to burn up!' It’s always 10 to 12 years down the road.”

In a debate with Democratic Gov. Jay Inslee, when asked what policies he would pursue to prevent climate change, Culp offered none.

“To have someone run for governor in the state of Washington following Donald Trump over this cliff into the abyss of climate change, that, I believe, is unacceptable in our state,” Inslee said.

Inslee ran for President this year as the climate candidate, though his efforts as governor have not prevented the state’s greenhouse gas emissions from increasing 6% since he became governor in 2012.

Conservative activist and recent University of Washington graduate Benji Backer told NPR he’s undecided about his vote for President.

"If President Trump wants to get my vote, he's going to have to prioritize climate change in a way that he has not done over the past four years," said Backer, who heads the market-oriented American Conservation Coalition.

Tyson Johnston with the Quinault Nation said another four years of inaction would be devastating to communities like his that are uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

“We cannot go on,” Johnston said. “It's kind of now or never, we feel, if we’re going to make a tangible difference in the lives of our future generations.”

September of this year was the world’s warmest on record, and we can expect records to keep falling as our climate heads into uncharted territory.

Whichever politicians win in November, they’ll have to face the disastrous consequences of a warming world—whether they try to stop it from getting worse or not.