The restored Elwha River, 'hidden gem' of the Olympic Peninsula: Travel For Good

At the north end of the Olympic Peninsula, trucks carrying massive trees rumble through the City of Port Angeles. Humans here have dramatically altered the old-growth forests that ring the snowy peaks of the mountains nearby. But residents are working to preserve what they can of this wilderness.

For many of them, their livelihood depends on it.

The Olympic National Park attracts a steady flow of visitors to Port Angeles. Most are seeking popular destinations, like the Hoh Rainforest, one of the largest temperate rainforests in the country. The area’s famous attractions tend to overshadow lesser-known spots, like the Elwha River, where a recent dam removal project has transformed swaths of the riverbank.

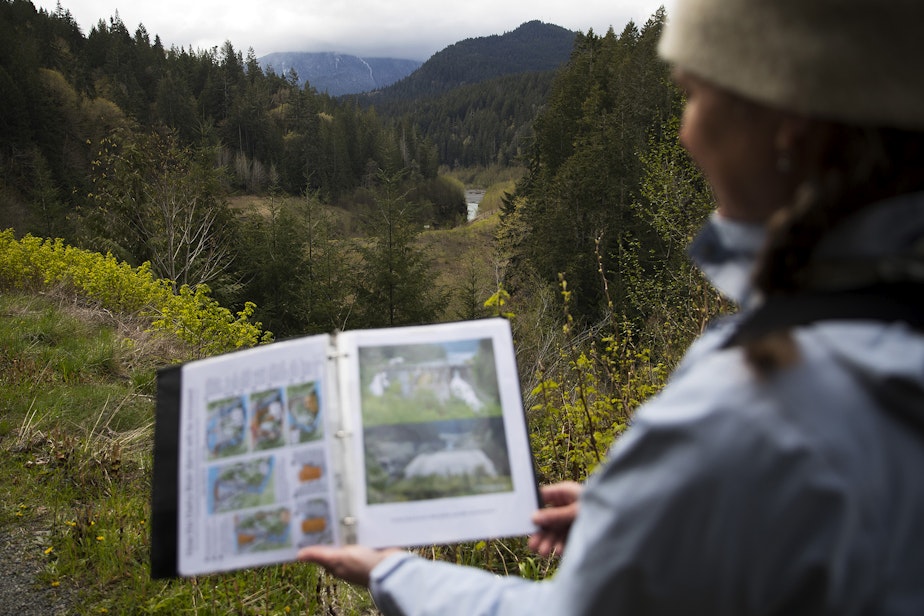

Port Angeles residents, like biologist Carolyn Wilcox, are eager to show off these hidden gems. Wilcox has a permit through the National Park Service to lead tours on and around park lands. On a brisk morning in April, she guided KUOW to the river to view the sites where two towering dams once stood.

“The Elwha has regional fame due to the amazing restoration and comeback of fish and ecosystem services,” Wilcox said. But, she added, “first-time visitors don't hear much about it.”

The Olympic Power Company dammed the river in the early 1900s to generate hydropower. First it built the 108-foot-tall Elwha Dam, followed by the 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam. The idea was to support what would become the City of Port Angeles and the booming logging industry around it.

Sponsored

But the dams blocked salmon migration and flooded Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe cultural sites.

Congress authorized the removal of the dams in 1992, and work finally began in 2011. The project was complete in 2014. At the time, it was the largest dam removal in U.S. history, according to the National Park Service.

With the pair of dams gone, the river has carved new channels, and the surrounding forest is hugging closer to the banks.

Standing where one of the dams used to be, Wilcox pulled out photos documenting the demolition. She pointed directly in front of her, to the spot where boxy, concrete structures once stood. In their place are young, yellow-green trees and swirling, turquoise water.

Sponsored

“I’ve never been to Alaska, but I’ve been told that our rivers here on the Olympic Peninsula, in the continental U.S., are the closest to what you would find in Alaska,” Wilcox said.

KUOW spent five hours trekking through the conifer forest around the Elwha. In that time, Wilcox pointed out a half-dozen bald eagles; a red-winged blackbird, which she said had previously been uncommon to the area; and three pairs of harlequin ducks.

Wilcox said the ducks come to the river because of a greater abundance of food, like tidal invertebrates and small fish. That wasn’t the case when the dams were still standing.

There are other signs of revitalization, too.

Sponsored

Wilcox pointed out areas where the river is “braiding,” creating smaller channels off the sides of the main river. Salmon prefer to nest in these channels, where there’s more sediment to protect their eggs from getting swept away.

Wilcox takes customers all over the Peninsula to see its hidden secrets and learn about what it takes to keep it thriving.

Her work helps Port Angeles thrive, too, in a way. She encourages her customers to stop there, spend the night at a local hotel and spend a little cash at small businesses.

The National Park Service says this kind of relationship with tourism motivates locals to protect the land.

Sponsored

And Wilcox hopes visitors will, too.

Much of the Elwha River is located within Olympic National Park. Visitors need a valid park pass or must pay an entrance fee. Vehicles with 15 or fewer passengers cost $30 to enter for up to seven consecutive days. Portions of the river, including one of the former dam sites, are located outside the park, and visitors can access the beach where the Elwha Rivers meets the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the north.

This piece is from our eight-part Travel For Good series, spotlighting tourism ideas across the state that teach about our fragile wonders and how we can help protect them. Check out more stories from the series here.

Want to share your social good travel ideas with us? Send an email to zhamid@kuow.org. We might feature your submission in future stories!

Sponsored

CORRECTION 5/19: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said both former dam sites are located outside Olympic National Park. In fact, the site where Glines Canyon Dam once stood is within the park's footprint.