This Auburn cop killed 3 and injured others. His department didn't stop him — outsiders did

T

he tattoos on his hands foreshadowed, in part, what was to come.

“JUDGED BY XII” on the right hand. “CARRIED BY VIII” on the left. Shorthand for an old policing proverb: “I’d rather be judged by 12” jurors than “carried by six” — or sometimes eight — pallbearers.

Officer Jeffrey Nelson had fired his gun with those hands, killing three men during his 12 years on the Auburn, Washington, police force.

He’d thrown punches with those hands, and used them to put a man in a chokehold. He’d placed those hands on his steering wheel, once ramming his police vehicle into a suspect.

Sponsored

Nelson now faces a murder charge for the killing of Jesse Sarey, 26, outside of a grocery store in 2019. Nelson is the first officer to be charged under Washington's Initiative 940, which eliminates a long-held legal standard of not charging officers in deadly force cases unless it can be proven they acted with "malice."

KUOW combed through lawsuits and police records, uncovering a litany of allegations that he has habitually engaged in abusive behavior, from three killings to daily indignities. Once, Nelson asked a fellow officer if he wanted to "fuck up" a man for jaywalking; he tased the man.

Each time, Nelson dodged discipline and instead received coaching and “corrective counseling,” or letters explaining his misconduct and how to improve his performance.

Excessive use of force extends beyond Nelson, and beyond Auburn. KUOW is examining use of force across King County and has found that officers are rarely disciplined in cases when the level of force used may have been unwarranted.

These officers say they leaned on tactics they had been trained to use — deploying tasers, placing people in chokeholds, and firing guns, for instance — and that their actions were justified because they feared for their lives in the line of duty.

Sponsored

Officer Nelson is an extreme example of what happens when this system goes unchecked.

T

wo years before Nelson was charged with murder in August 2020, a public defender in a federal criminal proceeding had sounded the alarm against him. Mohammad Ali Hamoudi had reviewed documents dating back to 2012, and wrote in court documents that Nelson had a “penchant towards violence” and had not been reprimanded by his superiors.

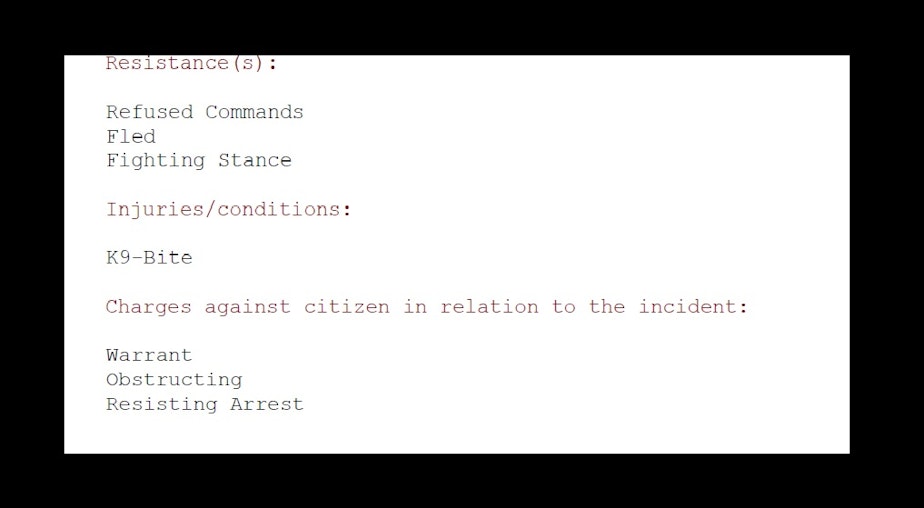

Hamoudi represented Joseph Allen, a 35-year-old Auburn man who encountered Nelson in August 2018. Allen was a wanted man, with a warrant for failing to appear to court.

Sponsored

Allen ran when he saw law enforcement in a Federal Way Walmart parking lot that day. Nelson, who assisted with the arrest, spotted Allen as he fled on foot.

Video footage shows Nelson speeding up and crushing Allen against a fence with his car. Allen suffered fractured ankles and a separated shoulder as a result. Nelson struck Allen with enough force to mangle the fence, photos show.

Five days later, Nelson wrote why he rammed into Allen.

He said that Allen was attempting to carjack a woman in a green Ford Explorer in the Walmart parking lot. He wrote that the woman had put her arms up.

The woman told a different story, however. She said Allen had grabbed the door handle and offered to pay her and her husband to hide him from police.

Sponsored

Nelson claimed that a U.S. Marshals briefing bulletin had called Allen “armed and extremely dangerous.” But Hamoudi, Allen's attorney, discovered the bulletin contained no such language.

Hamoudi combed through every document he could get on Nelson. He learned that Nelson had spent 12 years in the U.S. Army, deployed to Iraq twice, and was hired thereafter by the Auburn Police Department in 2008.

Hamoudi raised concerns to the court about whether the department had properly considered the specific training needs of a combat veteran transitioning to law enforcement. It wasn’t just Nelson’s pattern of behavior that concerned Hamoudi, but also the environment that enabled an officer to engage in such violent conduct without meaningful consequences.

“The records show that Nelson has a penchant towards violence and that the Auburn Police Department has been aware of it for some time,” Hamoudi wrote the court on May 24, 2019.

Seven days later, Nelson shot Jesse Sarey in the head.

Sponsored

N

ews stories of police force are usually about death. In Nelson’s case, three men died after he shot them each in the head:

Brian Scaman, May 7, 2011. Age 48. Shot once in the back of the head.

Nelson had encountered Scaman during a traffic stop. Scaman exited his vehicle and brandished a knife. Nelson shot him within less than a minute.

Isaiah Obet, June 10, 2017. Age 25. Shot once in the torso and again in the head. Obet was also bitten by Nelson’s police dog during the encounter.

Nelson confronted Obet in response to a call about a robbery, in which the suspect was possibly armed with a knife.

Nelson won a medal of valor for his encounter with Obet in June 2018. The City of Auburn settled with Obet's family for $1.25 million in August 2020, in response to a lawsuit over his death.

Jesse Sarey, May 31, 2019. Age 26. Shot once in the abdomen and, as he lay on the ground, shot again in the forehead.

Nelson encountered Sarey as he responded to calls that Sarey was behaving erratically on the premises of several businesses.

But Nelson has been accused of being a bad cop in other ways, too.

Documents obtained by KUOW outline the following:

January 2014

A citizen complaint is made to Auburn Police, saying that Nelson threw a homeless man’s bike and backpack into a Taco Bell dumpster, after the man was taken into custody.

Nelson admits to this, and receives written counseling.

May 2014

Nelson is accused of telling a man who had been assaulted, “I’m a combat vet, what have you done with your life other than getting busted in the face and laying in the hospital bed?”

Nelson denies this allegation.

July 2014

Nelson is caught on a recording asking a fellow officer if he wanted to “fuck up” a 21-year-old man who was jaywalking and trading foul language with Nelson. Nelson tases the man and places him in a neck hold.

Nelson receives written counseling.

December 2014

Nelson is accused of telling a juvenile who is being taken into custody, “I hope you don’t get raped.”

Nelson denies the allegation.

May 2017

Nelson pursues a suspect in his car, his emergency lights off, after the car chase is called off. The suspect speeds and weaves through traffic as Nelson keeps pace behind him.

An investigation finds that Nelson engaged in misconduct by failing to display emergency lights and sirens during the pursuit. No findings of insubordination are made.

May 2018

Nelson’s police K-9, Koen, bites a suspect who is cooperating.

An investigation finds that Nelson failed to maintain control of the German shepherd. Nelson receives training pointers, but no discipline.

Meanwhile, female officers and police staff also complained about Nelson, according to internal documents.

A group of employees wrote to human resources anonymously, to complain about Nelson in August 2014. He was “extremely” derogatory toward women, they wrote, and the sergeants that loved him did nothing to stop his indecent behavior.

Someone else had slipped an anonymous note into the mailbox of a colleague who had spoken up about Nelson in September 2014, saying that Nelson had other problems, too.

The author of that letter wrote that they were “fed up with officer Nelson and the others that are protected by the administration.”

It continued: “I heard him mocking the internal process again and nothing will happen of this. There were no specifics regarding his misconduct therefore the admin gaffed another internal. You need better ammunition to finally end his ability to endanger us and the public.”

After internal investigations, nothing became of these letters. Nelson's legal counsel did not return KUOW's request for comment.

Then there were the uses of force that Nelson's superiors deemed acceptable:

February 2017

Officer Nelson sees William Faas, a man he recognizes, at a Metro bus stop. Faas has a Pierce County warrant for pawning stolen machinery, and misdemeanor warrants out of Auburn.

As Nelson explains later in writing, he pulls over, and Faas walks away. That’s when Nelson opens his passenger door, releasing Koen, his police dog. Koen bites Faas on his arm. As Faas struggles, Nelson hits him in the face and shoulder.

Faas is transported to Auburn Regional Hospital.

Nelson admits to hitting Faas and says the man has a history of running.

Nelson’s use of force report goes through the chain of command, right up to the police chief. Document markings show they all sign off on the report, approving of Nelson’s actions.

Ten days later…

Nelson is working security at the Muckleshoot casino in Auburn, and is asked to remove a man from the premises, because he allegedly pushed another patron.

The man refuses to leave. Nelson writes in his report that the man smells of intoxicants and slurs his speech.

The man shoulder-checks Nelson, knocking him back. Nelson then comes up behind him and puts him in a neck restraint, or chokehold. The man goes unconscious.

Nelson’s own account moves its way up the chain of command, with no consequence.

These are just two accounts of more than a dozen that show that Nelson’s response was often not proportional to a civilian's suspected infraction.

B

etween 2017 and 2019, the rate of officers leaving the Auburn Police Department more than tripled. Concerned, the City of Auburn hired McGrath Consulting Group to study officer retention.

The consultants said some employees called the Auburn Police Department a “good old boy’s system,” characterized by bullying and resistance to change.

“What is more concerning is the laissez-faire response toward allegations of improper conduct by members within the department; and appears to be accepted within the current culture,” the report states.

Additionally, KUOW spoke with former Auburn detectives who described the department as having persistent issues with misogyny, negligent leadership, and sexual harassment.

About half the sergeants and police officers interviewed by the McGrath consultants said disciplinary issues were not handled fairly.

Then-Police Chief Bill Pierson told the consultants that discipline was determined on a case-by-case basis.

Pierson said he didn’t support a defined discipline matrix, and preferred flexibility. Unless the employee was put on unpaid leave, he explained, the human resources department was left out of the loop on discipline.

“There is no checks and balances process from outside the department currently in place,” the McGrath consultants wrote.

Chief Pierson left the department in November 2019, shortly after the McGrath study findings were handed over to city leadership.

The Auburn Police Department did not return comment to KUOW by the time this story was published.

T

he announcement that Nelson would be charged with murder came in the middle of an ongoing movement for racial justice and police accountability in the U.S.

After months of deliberation, King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg charged Officer Nelson with murder and assault for killing Jesse Sarey.

The felony charges stemmed from May 31, 2019, when Nelson responded to a call about a man behaving erratically at a Walgreens.

The man was 26-year-old Jesse Sarey, and witnesses reported seeing him throw things at vehicles and kick property late that afternoon.

Sarey eventually moved across the street, to Sunshine Grocery, where Nelson ultimately shot Sarey twice: Once in the torso, and again in the forehead, as Sarey lay incapacitated from the first shot.

Port of Seattle detectives, as part of the Valley Investigations Team — a group of investigators from several local law enforcement agencies — examined the police killing, and turned over their analysis to the King County Prosecutor’s Office.

"Our experts determined that Mr. Nelson did not follow his training in a number of ways, and those failures needlessly provoked the circumstances that led to Mr. Sarey’s death," Satterberg said in a statement announcing the charges.

The murder charge reflects the shot to the abdomen, which killed Sarey. The assault charge is for the bullet to Sarey's head, which the King County Medical Examiner determined wasn't immediately fatal.

"He did not de-escalate the situation," Satterberg said about Nelson. "He did not wait for backup."

In the last decade, five people have been killed by police officers in Auburn, court records state. Nelson fired the shots in three of those instances.

But in Sarey's case, the shooting happened in 2019, after Initiative 940 went into effect.

Before 2019, prosecutors had to demonstrate that an officer had acted with malice and a lack of good faith — a nearly impossible standard to prove, as it relied on officers retroactively sharing their thinking in the moment — to even charge them in deadly force cases.

As Satterberg put it the day he announced Nelson’s charges, the new law made it clear that there should be “an increased role for juries to decide whether a particular application of deadly force by law enforcement constitutes a crime.”

Nelson will stand before a jury of 12 who will determine whether he is guilty of murder. His trial will be scheduled following a November 17 court hearing.

And if he takes the stand, he will be instructed to raise his right hand — the one that says, “JUDGED BY XII.”