The untold story of Herbert Hightower, and Seattle Police’s history of killing people with knives

Castill Hightower woke to red and blue lights ricocheting off her bedroom walls. It was the middle of the night in north Seattle, and Hightower, then 17, saw police officers and flashing emergency vehicles outside her window.

In the living room, her mother checked in on her kids and realized that Herbert Hightower Jr., Castill’s older brother, was missing.

L

ess than an hour before, Seattle Police had descended on her apartment building after someone called to report a death. It was a false call, although someone would die that night: Within minutes of arriving on scene, at 1:19 a.m., an 11-year veteran cop and field training officer would shoot the man who made the call, because he said he was holding kitchen knives.

Seattle Police would later release details from that September night in 2004, deeming it a case of “suicide by cop.” Their reports would say what police officials would say for years to come as officers shot and killed others holding sharp-edged objects: Hightower had a knife, and knives are deadly weapons; the officer had no choice but to shoot.

Herbert Hightower is one of at least 13 people since 2004 who have been killed by Seattle Police because they were holding a knife. High profile deaths of people holding knives include John T. Williams, a First Nations woodcarver, and Charleena Lyles, a mother of four, who, like Hightower, was Black.

These are not accidents: Officers nationwide have been trained for decades to apply deadly force to someone near them who is brandishing a knife, combined with behavior perceived as threatening.

Police training has evolved since Hightower’s death in 2004, and officers are encouraged to slow down and consider the space between themselves and a suspect. People with mental illness, who encounter police often, are now more likely to be flagged in the system.

And yet, Seattle Police continue to kill people with knives once a year on average since 2014 – often individuals showing signs of mental distress.

Brian Maxey, chief operating officer for Seattle Police, said the department has focused on de-escalation, and that these tragedies don’t reflect the bigger picture: just 0.03% of crisis contacts over 2019 and 2020 included the highest level of force.

“We tend to focus on the negatives because they are so visceral, and we have video of them,” Maxey said. “But we have thousands of cases where things went really, really well.”

The city appears to be at an impasse when it comes to these particular fatal shootings. Police leaders say the numbers are negligible, and they point to gaps in the state’s mental health system. Meanwhile, the surviving families ask why an officer would shoot someone in distress, holding a steak knife as Hightower reportedly did, and why their loved ones couldn’t get help.

Hightower’s death got little media attention in 2004. It would be six years before a Seattle cop shooting would undergo forensic public scrutiny.

I

n 2010, John T. Williams, was a partially deaf woodcarver of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations, crossing Howell Street downtown with his carving knife. A patrol officer saw Williams and his knife, yelled at him to stop, and then shot and killed him. The officer resigned five and a half months later.

A year later in 2011, the Seattle Police Department came under federal scrutiny over allegations of excessive force. A subsequent Department of Justice investigation led to a consent decree, or federal oversight of the department.

Seattle is the only police department in the state that investigates its own cop shootings. That's because the department is exempt from a 2019 state law that says investigations must occur independent of the officer's agency. Seattle has this exemption because of the federal consent decree.

Cops are seldom killed by people with knives. In the years between 2017 and 2021, three officers were killed in the U.S. by knives or other edged weapons, according to data compiled by the FBI. None were in Seattle.

Maxey of Seattle Police said that hindsight suggests that some of these officers took calculated risks that didn’t pay off, and in many cases, officers were in close quarters with someone. But also, he said, their officers are trained to respond to lethal force with lethal force.

“There is no department in this country that will recommend you use a taser when you are being charged [by] someone with a knife,” Maxey said, adding that a taser is effective only 42 percent of the time, based on department analysis.

Since Hightower’s death, mental health issues have been a factor in many of Seattle’s cop-involved, fatal shootings of people holding knives, according to a KUOW review of news reports.

However, Maxey said officers are trained to react to people’s behaviors, not diagnose someone in the moment. Instead, officers are taught strategies to deescalate the situation.

“The label of mental health crisis isn’t particularly helpful, as it is designed to guide future interactions with that individual, not necessarily change the on-scene strategies,” Maxey said by email.

Despite the differences among these cases, a bladed object, no matter its size, is the common denominator — a reason for police to deploy their training to protect themselves. The Tueller Drill provided perspective on this.

What became widely known as the oversimplified “21-foot rule” stemmed from research in 1982, by then Sgt. Dennis Tueller. Tueller found that a suspect armed with an edged weapon was a threat within 21 feet, because they could reasonably reach an officer with a holstered gun before they grab their gun and fire two rounds.

Sean Hendrickson, an instructor at the Washington Criminal Justice Training Center, said the guideline has been misunderstood.

“It somehow got to the point where if someone has a knife at 21 feet, then they can stab you, so somehow the rule is you should shoot them, and that’s an oversimplification,” Hendrickson said.

While the insight behind the Tueller Drill is still sometimes taught at the academy where Seattle police get their training, Hendrickson said state training tells officers to slow down by managing distance and shielding.

Despite updated training, Seattle officers have strayed from de-escalation policy — as with the 2020 death of Terry Caver and 2021 death of Derek Hayden, both of whom had knives.

The Office of Police Accountability found the officers involved failed to de-escalate, but did not act outside the department’s policy on use of deadly force, which allows an officer to use deadly force when there’s imminent “threat of deadly or serious physical injury.” It also has to be objectively reasonable, necessary, and proportional.

It’s a higher bar than the legal standard.

The Seattle officer who fatally shot Caver, who allegedly pulled a knife on a pedestrian, got a 20-day suspension. The officers who killed Hayden, who held a knife to his own throat on an empty Seattle street while shouting “Please kill me,” received less than four days suspension each.

In response, the police department updated its edged-weapon de-escalation training, and plans to introduce BolaWrap, a remote restraint device.

H

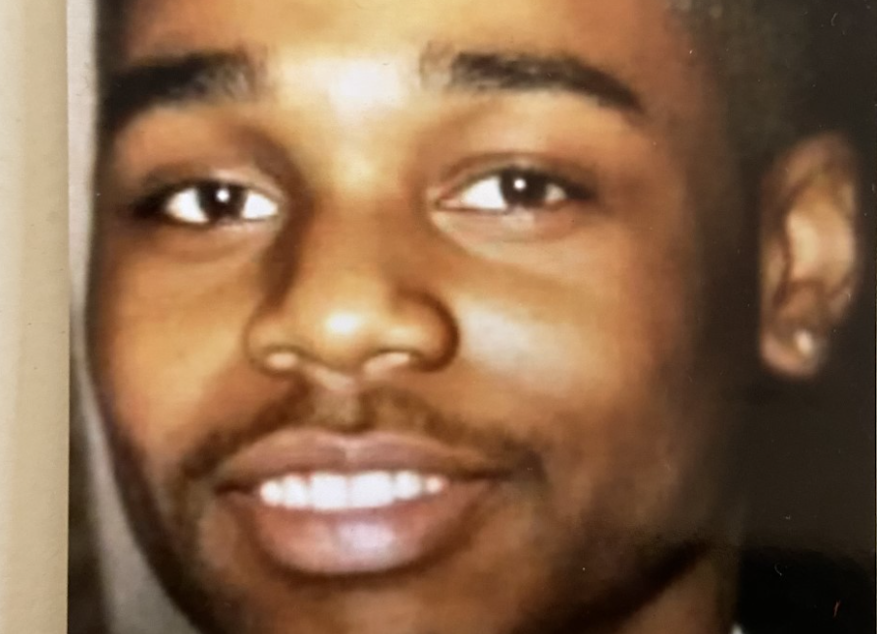

erbert Hightower was the second of five kids, described as warm and loving with an easy smile and an affinity for practical jokes. He loved Marvel comic books – Spiderman was his favorite – and spent his childhood exploring the Arkansas woods.

When he was 17, his older brother Andre died of a gunshot wound after a basketball game against another teen grew heated. The Hightowers then moved to Seattle to be closer to family.

Hightower met a girl in Seattle, and they had a son, who Hightower adored. Around the age of 25, after a trip back to Arkansas and a breakup with his son’s mom, his family noticed he was behaving strangely.

His mother Paula Woods said he seemed to be getting his “ducks in a row,” and that there were red flags she “just totally missed.”

Devastated by the breakup, it seemed Hightower came up with a plan, one that began with that fateful phone call outside a 7-Eleven in north Seattle on a cloudy night in September. “Somebody’s just been killed,” Hightower said calmly into the receiver.

He provided dispatchers the address where his ex-girlfriend lived with their 2-year-old son, near a Home Depot in an apartment above his mother’s place.

A sergeant nearby came across a man he later believed was Hightower. He slowed his patrol car, rolled down his window, and asked the man twice if he had just called 911 from a payphone. When the man didn’t respond or stop, the sergeant figured he wasn’t involved, and continued toward the apartment complex.

A mile south of the apartment complex at the North Precinct, Officer Steve Hirjak and his trainee Tara Durant heard the call over the radio. They hopped in a police car, and Durant drove them to the scene.

“I thought there was a good chance that this was a prank call because no one was waiting at the pay phone for officers, but on the chance that there really was a crime scene, I wanted her close enough to respond for training purposes,” Hirjak wrote in a statement two days later.

Seattle Police were at the scene when officers Hirjak and Durant arrived.

Hightower was walking on the shoulder of the road, Hirjak wrote, near a large cemetery where a security guard had spotted him earlier. The security guard told officers that Hightower seemed to be watching the scene, a behavior he later characterized to investigators as “being strange.”

An officer had just radioed that someone was approaching on foot, when Durant pulled up about 20 feet from Hightower, she wrote in her report.

Durant and Hirjak stepped out of the police car, and Durant headed for Hightower, who was walking away from her. Durant called for him to come back, according to police and witness accounts. Hightower turned to look at Durant and Hirjak, and then kept walking.

“Hey, what are you doing? Come over here,” Durant yelled, according to her written account.

This time, Hightower turned around and started walking back toward the officers. When Durant reached the front of the police vehicle, Hirjak yelled for her to back up, she wrote. Durant changed her instructions, yelling at Hightower to stay back, she wrote. But Hightower kept walking, heading for Hirjak.

“He’s got two knives in his hands,” Hirjak radioed.

Hirjak later wrote that he likely let Hightower get too close — that he was trained to believe that a bladed weapon could be lethal if within a 21-foot radius.

Hirjak yelled for Hightower to drop the knives. He didn’t, Hirjak wrote.

Hightower increased his speed, Hirjak wrote, although neighbors said they didn’t see him run. Fifteen seconds after Hirjak radioed dispatch about the knives, he shot his Glock, striking Hightower in the chest while he was roughly 15 feet from the officer.

Hightower fell to the ground, turned on his side and died. Police later found a handwritten note in his pocket, saying, “it’s time for me to end it,” and asking that his ex tell his son that he was a good father.

The apartment where a death had been reported was cleared.

The Hightower family said they do not believe the version of events police gave them. They said that in days that followed, details shared by police changed in ways that seemed to them to minimize blame that could be put on police. Body cameras were not affixed to Seattle police at this time.

Hirjak refused to be interviewed for this story. The Firearms Review Board cleared him of wrongdoing.

During a news conference, police command said Hirjak, 35, Korean American, was distraught over the shooting. He later married Tara Durant, his trainee, and they would start a nonprofit to train officers on use of force. Hirjak would speak at conferences, urging chiefs to change their culture.

Within the department, Hirjak advanced. For more than four years, he oversaw investigations into fatal use of force incidents — including that of Charleena Lyles and Che Taylor — as a lieutenant and captain of the department’s force investigation team. By 2018, he was commander for education and training, helping to develop new techniques, including in use of force.

The Hightower family, meanwhile, reeled. The impact of losing another child weighed heavily on Hightower’s parents, siblings, and also his son, who, at age 2, stopped talking.

“For days, I just wanted to stay in bed and cry,” Hightower’s mother Paula Woods said.

C

astill Hightower began to advocate for her brother in 2020, encouraged by the national civil rights movement against police violence, and inspired by families marching and speaking out on behalf of loved ones.

Castill watched a video from the protests that resonated. “Why are you out here?” someone asked a mom in the clip. The woman held a sign with a photo of her son, who was killed more than 20 years before.

“‘If I'm not out here, nobody will be out here,’” Castill recalled the woman saying. “‘If I don't fight for him, nobody will.’”

Castill Hightower said her family got no support from the local NAACP chapter after her brother died. Carl Mack, then chapter president, told media he felt it was a “classic example of suicide-by-cop” but never reached out to the family.

“I simply view it as a tragedy,” Mack told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

In a phone call Saturday, Mack’s retelling of those events 18 years ago differed from police reports reviewed by KUOW. What he remembered police telling him was that Hightower had broken through police tape near the crime scene — which wasn’t true. Hightower had walked toward police, and broke through no police tape.

But Mack was close with then-police Chief Gil Kerlikowske, who he said had never given him a reason to doubt him. Mack said that if he’d heard the accurate account, he would have gotten involved. Kerlikowske could not be reached for comment.

And so, Mack said, “I moved on.”

The Hightower family is still hoping to see change.

“There are generational effects of police violence, that often go unseen,” Castill Hightower said. “There is a level of trauma that goes into having to convince people to care.”

Now an adult, Castill Hightower is fighting for her brother. She requested and then publicly demanded police records from the night of her brother’s death. They were released. A mural of Herbert Hightower was unveiled in Burien earlier this year. She launched a GoFundMe campaign to hire an attorney and private investigator to have Hightower’s case reopened.

Most recently, Castill Hightower has pushed Seattle city leaders to earmark money for families of those killed and harmed by police violence. She coined it the “Impacted People’s Budget.”

She said the City of Seattle has to be “the first stop for accountability.”

“My brother was here,” Castill Hightower said. “He existed. He mattered.”

Reach reporter Ashley Hiruko directly at hiruko@kuow.org.