The often unheard Black journey: My great-great-grandmother’s migration story

Black Americans are often left out of American resettlement narratives. But many have rich stories pertaining to the Great Migration of the 20th century, during which Black families moved from the rural South to northern states in pursuit of a better life.

RadioActive's Indigo Mays learned about the story of her great-great-grandmother, Rosie Short Robinson, as told through her grandmother Carol Chism.

Content note: This story contains depictions of racist violence. Please take care when listening.

[RadioActive Youth Media is KUOW's radio journalism and audio storytelling program for young people. This story was entirely youth-produced, from the writing to the audio editing.]

M

y introduction to the Great Migration was after my mother had brought me to an art exhibit by Jacob Lawrence.

There, I saw a painting of many families packed into a train car. My mother leaned over and whispered to me, saying that our family had been part of the Great Migration.

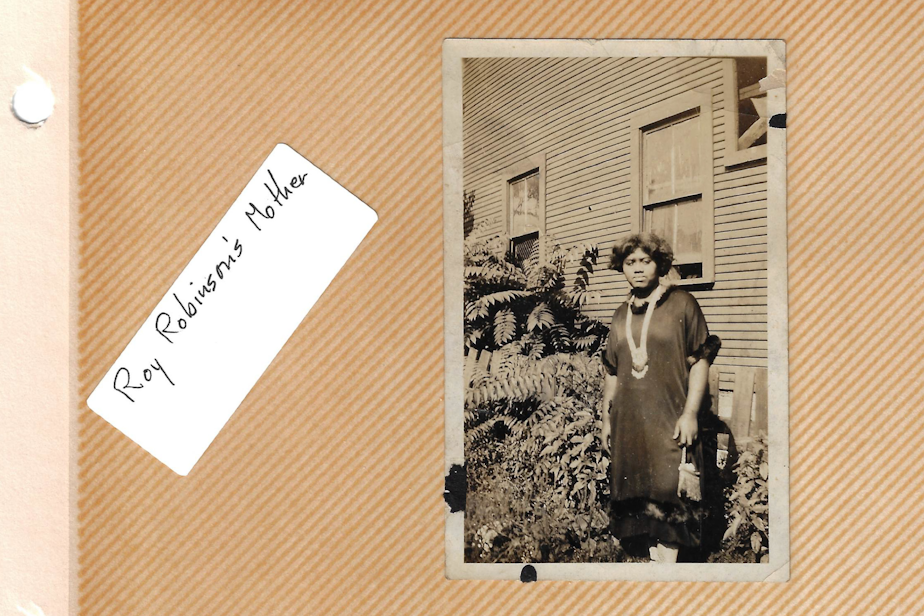

"Rosa Short Robinson is my father's mother. And I never got to meet her," my grandmother, Carol Chism, told me. "She passed when my father was a child. I've only known her through the verbal histories that I've received from my family members."

Sponsored

Rosie was probably born in Bogalusa, Louisiana in the late 1890s, though we aren’t completely sure. Rosie lived there during the Jim Crow era, a time in which Black people weren’t enslaved but were still treated as second-class citizens.

As my grandmother recalled the reality of Rosie, she sat in a comfy office surrounded by books — something Rosie could only dream of.

Rosie worked as a maid for white families and had little choice when it came to her work, like most Black residents of Bogalusa, who were compelled to work jobs mostly in service to their white counterparts.

"If she had refused, then she could have been beaten," my grandmother said. "And what they would do, sometimes, they had paddy rollers — they were really young guys who would just roll through the Black community. And if they heard of an insult, then they would find the person who was allegedly insulting someone in the white community. And they would tie them to a tree in the middle of the community and whip them."

Rosie tried to give her three children the best life she could. But it was difficult, given the conditions of poverty, racism, and being a single mother.

Sponsored

Many Black Americans were already moving North, like Rosie’s husband, who had moved to Youngstown, Ohio for the steel mills.

But the thing is, white people made it difficult for Black residents to just pack up and leave. To them, losing out on nearly free labor was unimaginable.

So Rosie Short Robinson had to sneak out of Louisiana.

"What she did was pretend that she was going to visit relatives in Mississippi," my grandmother said. "And she packed her clothes, only enough to take a trip. She sold some of her furniture to people that she could trust. And then she caught the train to Mississippi."

Sponsored

There were still many trials in Ohio, and racism didn’t just disappear after leaving the South. Rosie died a few years after moving to Youngstown, due to a lack of health care access. Many doctors wouldn't even see Black families at that time.

But her decision to move the family North still lived on. Her daughter was able to finish the eighth grade. Her youngest son finished high school. And her oldest son, my grandmother's Uncle Willie, was able to join the army, making a career out of working in supply depots.

"He probably would not have had a career if they had not moved to Ohio, because opportunities in the South were not available," my grandma said.

From what my grandma had heard, Rosie was a good mother. She raised three kids largely on her own, showing them love and care for their entire lives. Her kids carried on the legacy of her love by housing other Black families during the Great Migration. My grandmother can still remember those seeking refuge.

"All of the people who lived there, I used to call aunts and uncles," she said. "Because you were respectful to older people. They were all your aunt or your uncle."

Sponsored

Rosie Short Robinson’s spirit still lingers around my family today, even though none of us ever got to meet her.

The monumental decision to move North affected the trajectory of our family. But so did her persistence — a persistence that has remained intact for generations.

"Even now, our family has a history of women who have always worked outside of the home," my grandmother said. "We've had a history of women who were creative, and artistic, and who had a strong sense of efficacy and being able to make good things happen for their family."

This story was produced in a RadioActive Youth Media one-week Intro to Radio Storytelling workshop for high school-age youth.

Production assistance by Troy Landrum Jr. and Jared Lam. Prepared for the web by Kelsey Kupferer.