The Northwest’s unhealthy new season: smoke

A lot of people started wearing N95 masks during the Covid-19 pandemic. Cori Adler of Seattle started wearing one seven years prior, for her bicycle commute.

“During the wildfire season, it's not really safe to be breathing that hard on your bicycle, to be breathing all of that smoke,” Adler said.

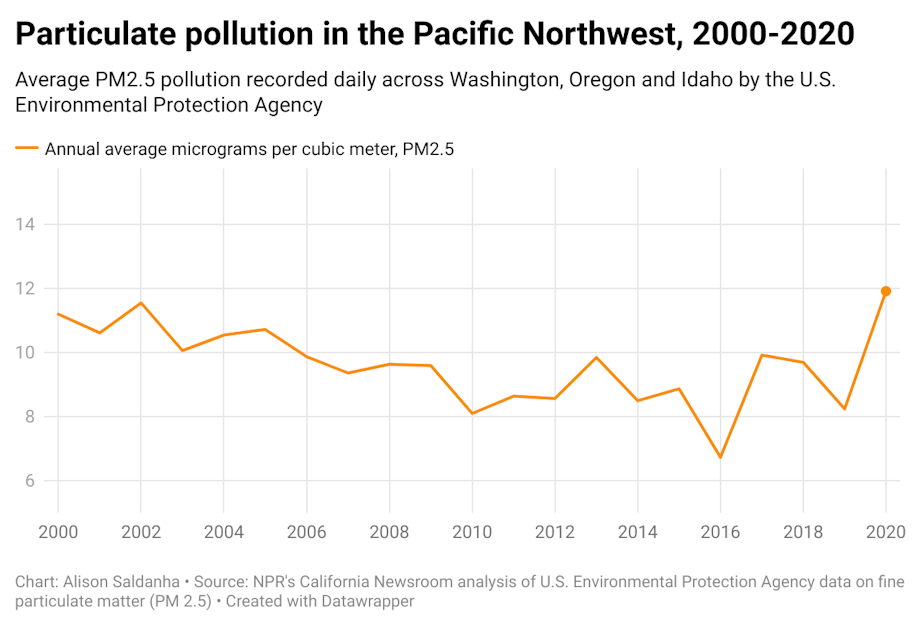

Unhealthy, smoky air has quickly become an unfortunate fact of summer life as a hotter climate fuels more fires across the West.

When Kelsey Horne and her husband graduated from Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma in 2010, the climate was different.

“Fire season wasn't a thing,” she said. “We didn't talk about wildfires. We didn't talk about getting ready for wildfire season.”

A decade later, Tacoma and the rest of the Northwest endure weeks of smoke from local fires and faraway ones.

Sponsored

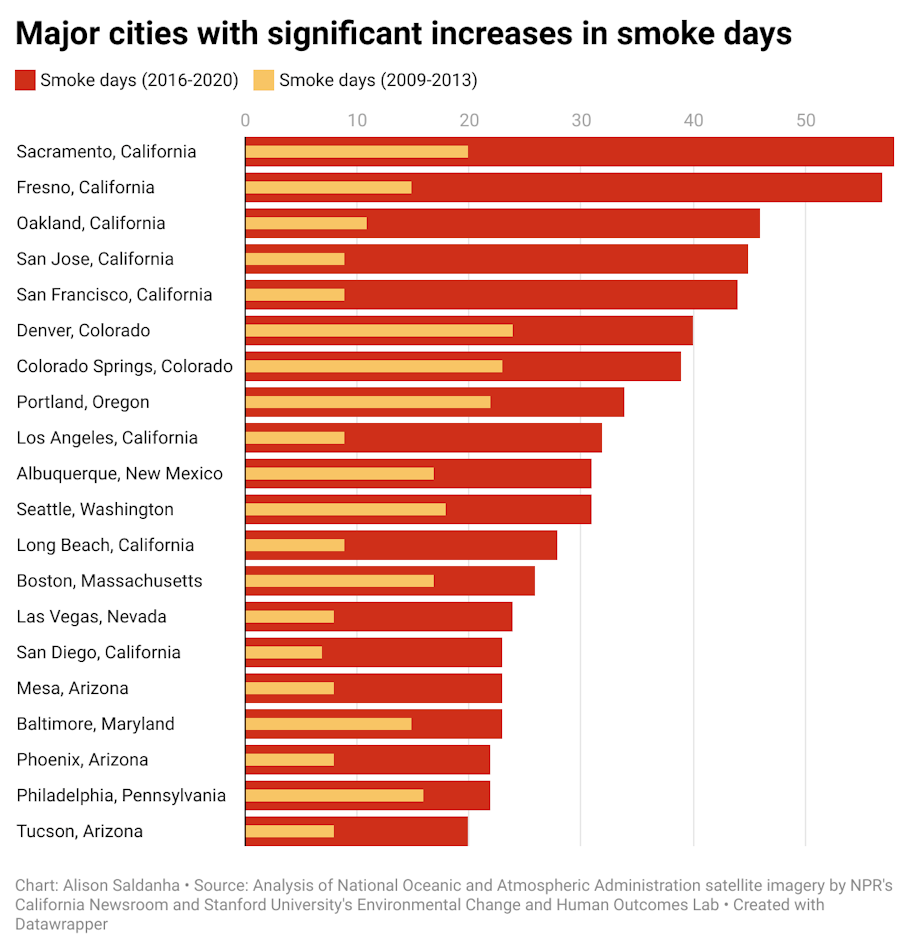

The same trend threatens lungs and lives across the country, according to an analysis of federal satellite imagery by NPR’s California Newsroom and Stanford University’s Environmental Change and Human Outcomes Lab.

Far-reaching plumes of pollution from wildfires have become so much more common that most of the United States breathes smoky air for weeks each year.

To look past year-to-year fluctuations, the NPR and Stanford researchers compared two five-year periods: 2009-2013 and 2016-2020.

Tacoma’s Pierce County now averages 30 days of smoke each year; Seattle’s King County averages 31 days of smoke each year. Both are up by more than half from less than a decade ago.

Sponsored

Eight counties in eastern Washington average at least 50 days under smoky skies annually.

Tiny particulates in wildfire smoke known as PM2.5 trigger more asthma attacks, more trips to the ER, and more deaths. One in seven families in Washington include someone with asthma, according to University of Washington-Tacoma nursing professor Robin Evans-Agnew.

Black people, Native Americans, and people with low incomes are most likely to end up in the hospital from a smoky-day asthma attack, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asians and Latinos are less likely to have asthma than the national average.

“Who’s going to suffer the most?” Evans-Agnew asked. “It’s not going to be someone living in a nice house with air conditioning, right? It’s going to be someone living in a small, substandard apartment or trailer home, whose parents are gone most of the day, working.”

Sponsored

“For these low-income communities or households, it's hard to buy HEPA filters or MERV filters” — filters fine enough to trap the tiny particles that could otherwise lodge deep in the lungs — air pollution researcher Yisi Liu said.

In a study published in April, Liu and her University of Washington colleagues estimated that just 13 days of smoky, particulate-filled air in 2020 killed 38 to 92 people in Washington state.

The risk of dying from a respiratory disease in Washington state increased by 9% on a day with wildfire smoke and 5% the next day, according to a 2020 study by University of Washington and state agency researchers. The same-day risk rose 35% for adults ages 45–64.

“Low-income communities and outdoor workers need more resources to be prepared for future wildfire seasons,” said Liu, now a postdoc at the University of Southern California.

Sponsored

Climate experts say adapting to our hotter and smokier reality is essential — as is stopping the heat-trapping pollution that keeps pushing the global climate to new extremes.

In Tacoma, the Hornes had a baby in 2019, a year before the West’s smokiest summer on record.

“We were definitely worried for our baby,” Horne said. “The younger age group and those with respiratory illnesses, and those who are a little older, they typically have a higher susceptibility to lower air quality.”

The Hornes invested in air filters for their home, and they mostly stay inside on smoky days to protect their baby’s delicate lungs as well as their own. Husband David Horne also took to wearing a full-face respirator he has from his job as a geologist to work in the garden on smoky days.

“This is certainly something that we felt very privileged to have access to,” Kelsey Horne said. “It's important to make access to safety equipment accessible to everyone, and that certainly isn't the case right now.”

Sponsored

King County distributed filter-fans to 800 low-income families in 2020, in a county with 2.25 million residents. The Puget Sound Clean Air Agency gave out another 600 fans.

In the smoke-choked Methow Valley, east of the North Cascades, the nonprofit Methow Valley Citizens Council gave out a “limited supply” of N95 masks and kits for making filter fans this summer to people too poor to buy the protective equipment.

“Wildfires are going to be part of our everyday, or our summer realities from now on, just like we're preparing for next year's heat wave,” Kelsey Horne said.

“Let's not call it wildfire smoke anymore. Let's call it anthropogenic-caused smoke, right? This is human related,” Evans-Agnew said. “These are not necessarily wildfires that have been set by humans, but human-caused climate change is setting these wildfires at a higher rate.”

“We're doing this. We are causing this,” he said.

Smoke from climate-fueled fires hit most of the West Coast hard in 2021, while westerly winds off the Pacific gave the Olympic Peninsula and the Puget Sound region a bit of a breather.

"We had this almost, near-perfect air-flow regime bringing clean marine air inland this summer, for most of this summer, so we just lucked out," Ranil Dhammapala with the Washington state Department of Ecology said.

“We should count our blessings this year and not keep expecting the same year after year," Dhammapala said.

September rains have doused most Northwest fires by now, but fire season in California continues into November. With smoke able to travel hundreds of miles, even cross a continent, smoky skies could still return to the Northwest sooner than anyone would like.

Additional reporting by Paige Browning.

If you have any feedback on this story, you can email me at jryan@kuow.org or find me on Twitter @heyjohnryan. Or you can just click the feedback button on the edge of this page. We're listening.