Displacement is a big problem in Seattle. Subsidized apartments help, but only somewhat

Seattle must, by state law, make room for newcomers to live. But that growth is pushing people out, especially Black and immigrant families.

Some people are trying to help ease displacement in Seattle by organizing communities and chasing grants, in order to build subsidized affordable apartments.

But critics warn that we need to increase homeownership opportunities, too.

Fardowsa Salad is a Somali American who runs a small grocery store called Sharif Grocery and Halal on Rainier Avenue. She’s been watching as rents have risen in Rainier Beach, the neighborhood around her store.

It’s been driving her customers away.

“We had a lot of customers that moved to Federal Way," she said. Salad would find out when the customers show up in the store, after a long absence. "And when we ask, they say 'Oh, we moved over there. The rent is too high.'”

Now, her store's future is uncertain.

“We’re wishing the best," Salad said. "But I don’t know, if this continues — maybe we will end up being just pushed away, too.”

Sponsored

Displacement isn’t just about people losing their homes — it’s also about losing the businesses that sustain people in a neighborhood, like a halal market.

Lost opportunities

One customer who's trying to stay in the neighborhood, even as her rent rises, is Hafsa Don.

Before her rent went up, she and her sister were trying to get computer science degrees, so they could work at Microsoft or Amazon.

That didn't work out.

Sponsored

“Because we’re refugees, and we literally came her like five years ago, and we’re trying to live on our own, and so to pay the rent, and living and everything in America, we definitely need jobs," Don said. "So I decided to find a job and let my sister finish her BA.”

Now, Don works as a preschool teacher, which obviously doesn’t pay as much as a tech salary.

Recently, their rent went up a second time.

The two of them are trying to hang on, because moving to Federal Way would make their commutes much longer. Hafsa Don said she’d also have to get a car, and she can’t afford a car.

Sponsored

Now, her sister is going to have to get a job, too.

You can see the cascading catastrophe that displacement causes for people who are just trying to improve their lives. And the city loses a rich layer of our society when a pre-school teacher and a student can't stay in town.

Seattle has made some progress in its effort to fight displacement. But those small steps are overwhelmed by larger trends rooted in harmful land use practices from the past.

Next, we'll look at strategies that help — and examine their limitations.

A partial solution: subsidized affordable apartments

Sponsored

The city of Seattle, and Washington state, are investing a lot of money in subsidized affordable apartment buildings. These are mostly large buildings with lots of units on busy arterial streets.

Many of these buildings are in Urban Villages. These designated growth centers make up 21% of the city's residential land, but they take 83% of the city's growth.

Sophia Benalfew stands outside a new affordable apartment building under construction on Rainier Avenue. It’s a project called Ethiopian Village. It’s five stories tall, and it’s currently surrounded by scaffolding wrapped in fabric containing the colors of the Ethiopian flag – red, gold, and green.

“It’s all about what we can do when we put our minds to it and work hard together,” she said.

Sponsored

Benalfew is the executive director of Ethiopian Community in Seattle, a non-profit that supports people of Ethiopian descent through navigating the challenges of immigration. She said the community spent years organizing neighbors, lobbying politicians, chasing after grants, and shaping the housing project.

“When we started, it sounded more like a dream,” she said. But that dream has now become 90 discount apartments targeted for Ethiopian seniors.

“There’s a lot of excitement in the community. We get calls asking us when they can register.”

Projects like this are definitely having an impact. The city currently helps subsidize over 15,000 affordable apartments. About 22% of those are in South Seattle, in District 2.

But those homes aren’t abundant enough – or cheap enough – to help everyone. Maktub Abdi is an Uber driver who's been looking for an affordable apartment in Rainier Beach for his large family.

“If you go down the Rainier here, if you go there they say, ‘Oh, it’s an affordable house,’ and stuff like that," Abdi said. "But when you call them over, it’s just the same thing – what we’re paying right now. That’s not affordable housing. Affordable housing should be something lower than that.”

Abdi said affordable for him, his wife and three kids would mean a 3 bedroom apartment for $1,200. They currently pay $1,600.

Statistically, over a quarter of Black King County residents say they probably can’t make their next rent payment, or mortgage payment. And they are 10 times more likely to face eviction or foreclosure than their white neighbors.

Read more about these statistics on the "demographics" tab of this page: https://kingcounty.gov/depts/health/covid-19/data/impacts/housing.aspx

To understand why this is, you really have to look at history.

The deep roots of Seattle's displacement

Reginald Dennis has lived that history. Currently, he's a renter in the Rainier Valley who fears he might be priced out soon.

Dennis, who is African American, grew up in Seattle's Central Area neighborhood, north of the Rainier Valley, in the 1960s and 1970s. And he said he's seen this pattern play out before.

“It was a working class community," he said. "And everybody I knew – their parents owned the homes that they were living in.”

Dennis said the reason for this was a racist practice called redlining. Banks wouldn’t loan money to purchase or fix up homes in his neighborhood, because it was seen as “declining.”

Redlining pushed home prices down. Dennis said this enabled many Black families to purchase homes, even though they didn't have assistance from banks.

Later, as Seattle ran out of room to grow, white families – and the banks that finance their purchases – were drawn to the Central Area, for its affordability.

As a young man, Dennis said, he could see where this would lead. He told his friends they would eventually leave.

“And some of them would argue and say, 'Well, I’m never gonna sell... I’m gonna stay here.' And I didn’t try to argue with that, I’d say, 'Maybe you will. Maybe you’ll stay around. But you’ll watch your neighbors disappear one by one.' And that’s just what happened.”

As for what happened to all that Black homeownership in the neighborhood where he grew up, Dennis said people were priced out. A lot of Black families had lower incomes. And even though redlining had technically ended, Black families were at a disadvantage, compared to white families, when it came to getting loans to refinance or fix up their homes.

Even in recent years, data shows Black and Latino people are denied conventional mortgages at a higher rate than white people, even when you control for factors like income and loan amount.

Dennis' experience growing up in the Central Area gives him a different lens with which to view the new subsidized apartment buildings being built at the southern end of the Rainier Valley today.

"A lot of these actions seem to be geared towards rental units, and nothing to do with establishing or trying to recreate a base.”

Dennis is calling out the status quo – where we look to subsidized apartments instead of homeownership – to solve the problem.

“I think it’s not enough," he said. "I can’t see that it would lead to a dramatic change, or that it would lead to any type of ownership in the community."

Dennis is comparing the current situation to the neighborhood where he grew up, where Black families owned homes. He said that was a vital part of what made that community thrive.

There are similarities between the erosion of the Central Area’s Black community in Seattle and the destruction of what was called Black Wall Street, in Tulsa Oklahoma in 1921. In Tulsa, it was racist violence – arson and murder – that brought down the neighborhood, where so many Black families had built wealth.

In Seattle, it was economics.

Asked to sum up that history, Dennis said, “I think if I wanted people to know anything, I would want them to know the harm that the gentrification has caused, and that the impact of that has destroyed a viable, functioning community that really had the potential to grow.”

Dennis said the same thing is happening today, in areas like Rainier Beach. And so he wants it to be easier for people on limited incomes to buy homes.

Generational wealth is achieved, in most middle and upper class white American families, through home ownership. And Reginald Dennis is seeing that goal getting further and further away for his community, which is replaying injustices of the past.

Getting Black families on board the homeownership train may require a different kind of subsidy, he said.

Seattle begins to address the past

The city of Seattle is updating its comprehensive plan. This is the first time the city will be going through that process since the 2020 protests for racial justice, which called on the city to fund economic initiatives that support people of color.

As this important update moves forward, we are seeing a sea of change in how officials talk about racist land use practices from the past. Seattle planners appear to be focused on examining how the city grows using a racial equity lens.

There’s a growing recognition that the city’s current growth strategy, of channeling 83% of new housing into dense parts of the city called Urban Villages, has not reversed the displacement of Black and Latino families from the city.

The current strategy also created another problem, by turning low density neighborhoods into exclusive enclaves, making it very difficult for people on lower incomes to afford homes there. The city considers this a bad outcome since those neighborhoods offer a lot of opportunities that would help low income families improve their lives: access to parks, schools, and networking opportunities with neighbors that can lead to job opportunities.

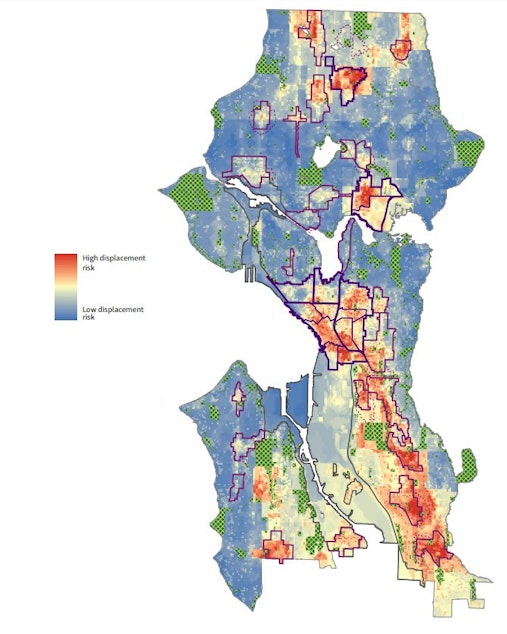

In multiple publications, the city points to a heat map showing displacement risk. Parts of the Rainier Valley show up as bright spots on that heat map. The city regularly points to the need to update the way it defines displacement risk, to account for more kinds of harm, including displacement of stores and the decreasing ability of low-income familes to afford relatively exclusive lower-density neighborhoods.

The goal of all this talk is to develop a stronger response to the problem of displacement , so that more Black, Latino, and immigrant families, as well as other vulnerable communities, can stay in Seattle.

It seems most likely, based on how the city talks about the limitations of the current comprehensive plan, that the city will update its plan with a two-pronged approach.

First: more areas will be opened up to subsidized apartments, such as Ethiopian Village.

Second: in order to increase opportunities for home ownership, some parts of the city that have been mostly off limits to development – areas dominated by single family homes – will be opened up a bit, so that more affordable kinds of homes can be built there. We could see those neighborhoods opened up to duplexes, triplexes, quads, townhomes, and maybe small apartment buildings.

How far Seattle – and other cities in the region that are also updating their comprehensive plans – choose to take those reforms remains to be seen.

KUOW will be following this story to see if the follow-through is in line with the city's early, strong language about potential reforms.

The city of Seattle is taking public comment right now on how much it should rethink its current growth strategy as it updates its comprehensive plan. The public comment period ends Monday, Aug. 22 at 5pm.

You can submit your input here.