'Forbidden houses of Bothell' show how multifamily housing fits into single-family zones

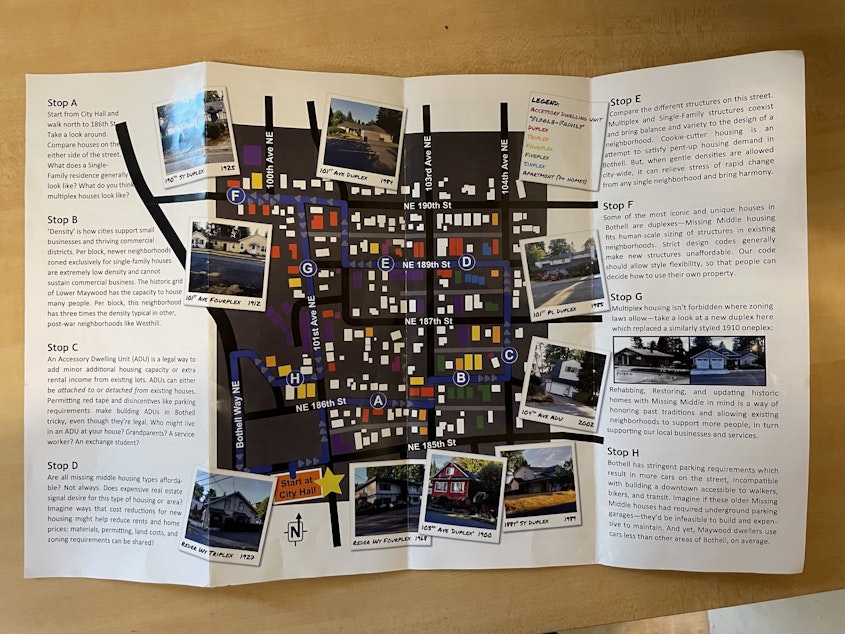

Advocates for "missing middle" housing put together a walking tour to show how duplexes, triplexes, and small apartment buildings can fit into a single-family neighborhood.

The mayor of Auburn gives her own walking tour, arguing against the idea.

The competing tours offer different perspectives on a bill that would open single-family zones to more types of housing in Washington state.

C

ary Westerbeck and Amanda Dodd stop in front of a small duplex in Bothell's oldest neighborhood, Lower Maywood Hills.

At around 1,500 square feet or so, the one story rambler is smaller, Westerbeck says, than most single-family homes built today.

"It just happens to be divided in the middle into two homes,” Westerbeck says. "It's 'forbidden because it's illegal to build in most of Bothell today."

In truth, it's illegal on much of the urban land in Washington state, where single-family zones preserve land for one house, with one front door. The duplex, of course, has two.

Sponsored

Westerbeck and Dodd sit on Bothell's planning commission. They're part of a group that put together this walking tour, called "The Forbidden Houses of Bothell," to advocate for more "missing middle housing," and to show people that it can coexist peacefully among single-family homes.

The walking tour has become especially useful as Washingtonians try to understand the implications of a "missing middle" bill making its way through Olympia.

The senate and house versions of the bill both would open up land currently reserved for single-family residences to denser kinds of housing. They've won broad support among a variety of planners and housing advocates while drawing criticism from many mayors, who want to retain local control over zoning decisions.

This week will determine whether the bill dies in committee or moves on to become part of a wider discussion in the Legislature.

Sponsored

Because this neighborhood is older, closer to downtown Bothell, and has more permissive zoning than other parts of Bothell, Lower Maywood Hills has added homes like this incrementally over the years.

A

s we’re standing there, Bonnie Mackay and her brother Robert, who uses a wheelchair, come outside. Her brother lives here, within walking distance of the old Safeway where he worked for 30 years as head courtesy clerk.

The occupant of the other side is the Mackays' 91-year-old mother, who owns the building. Bonnie Mackay says this little duplex has been at the core of her extended family.

Sponsored

“It has housed a lot of family members. My parents have always lived on one side — and then they’ve either let kids or grandkids come and live with them. At one time, they rented it out a bit. But at one time, it was a daycare for the grandkids in the family.”

Over the years, the family tried to build more places for relatives to live nearby, but ran into zoning problems. More recently, when Bonnie Mackay’s son lost his job during the pandemic, they wanted to build him a tiny cottage in the big backyard of the duplex. But due to a technicality, they were not allowed to.

Asked about this property, the city explained that even though the lot is zoned for four units, backyard cottages are defined as accessory to single-family residences — not duplexes.

“You know, like right now, I have an 8-year-old grandson — and then a baby granddaughter on the way — and I would like to be their caretaker," Bonnie Mackay says. "But my kids have had to move to Eastern Washington to find something affordable.”

The city of Bothell says the technicality that prevented the Mackays from building a home here should not have. More broadly, Bothell's working on making things easier for families like this. For example, the right to build duplexes has spread to other parts of the city, at least on corner lots.

Sponsored

Such changes could also help low-income and underrepresented families that zoning laws have historically kept out of these neighborhoods.

PHOTOS: A tour of Bothell's "missing middle" homes

But Amanda Dodd, who sits on the planning commission here and is a "Forbidden Houses of Bothell" tour guide, says we need these changes state wide.

“It’s like the folks we just talked to, the Mackay family — they couldn’t put a tiny house in their backyard for their grandson, so he’s got to go somewhere else. If you can’t allow incremental change in neighborhoods, they’re going to be torn down and be completely rebuilt over time, as homeowners need to seek other solutions that work for their families.”

Sponsored

The rest of the tour takes us past triplexes, townhomes, and small apartment buildings — all mixed in with older single-family homes.

S

ome critics of the "missing middle" bill worry that looser zoning laws could cause homes like these to be torn down and replaced with something more expensive. That has led Nancy Backus to oppose this bill. She’s the mayor of Auburn.

I meet her on a quiet little street in her town. It’s a lot like the street in Bothell, with a mix of housing types. But the homes here often sell for half the price of homes in that Bothell neighborhood.

Backus says she’s not against adding density. She just doesn’t think it works on streets like this one.

“And there are areas in our city that it would be the perfect opportunity to redevelop. But there would be neighborhoods like this that would be exposed to demolition that we just don’t think is right," she says.

"There’s a lot of history in Auburn — a lot of history in these homes. A lot of these homes are second generation and third generation owned, and losing that I think would be losing a part of Auburn’s history and something I think is really precious to us,” she adds.

Backus has other reasons to oppose the law. She says the city’s infrastructure can’t support a bunch of new homes on every property.

She also says the city spent lots of time figuring out where growth works in Auburn. The proposed state law, she says, would steamroll those local plans.

PHOTOS: A tour of Auburn's Les Gove neighborhood and beyond

N

ot every Auburn resident agrees with Backus' stance, though.

Tim Wallace is working in his backyard, nearby. He says while he agrees with the mayor that too much growth would be bad, on a personal level, he wishes the city would let him expand his home.

He has an aunt, who he says practically raised him, and took care of his own mother at the end of her life. That aunt is ailing now, and Wallace says he would love to build a backyard cottage for her. Those are technically legal in Auburn, but there are a lot of restrictions: in his case, 20-foot setbacks on two sides of his property. So he can’t do it.

“It’s hard for me to describe the amount of frustration — trying to do what feels like the right thing my whole life, to get to the point where I can help my family — and then I’m getting held up by red tape."

Wallace says his aunt has had to move to Eastern Washington, where she’s lost access to all the doctors she needs.

“It’s really hindered the quality of her life,” he says.

Cities across the state have made some small changes to single-family zoning codes, to crack the door on denser development. But Josh Brown, head of the Puget Sound Regional Council, says homebuilders in Washington state still haven't caught up with all the people who moved here during the tech boom that followed the great recession.

Because there's such a shortage of homes, many experts say the first wave of homes built under looser rules will likely be expensive, targeting the top of the market — much like the townhomes being built in Seattle and other cities today, in the limited areas where they're allowed.

Home prices in Washington state increased by 19% in 2021. But over time, advocates for the bill say an additional supply of "missing middle" housing structures should drive housing prices down.