Sorry, climate: Washington state's carbon emissions stay stubbornly high

Washington state’s carbon emissions remain stubbornly high, despite the efforts of Gov. Jay Inslee and others to rein in the climate-wrecking pollution, according to the latest numbers from the Washington Department of Ecology.

Washington’s greenhouse gas emissions rose 1.7 percent in 2016 and remained virtually unchanged in 2017, at 97.5 million tons, according to the state’s newest inventory, released on Tuesday.

The numbers are bad news for the climate and for a governor who has staked his national reputation on defeating climate change.

“We have to get a handle on transportation pollution,” Inslee told KUOW’s Bill Radke.

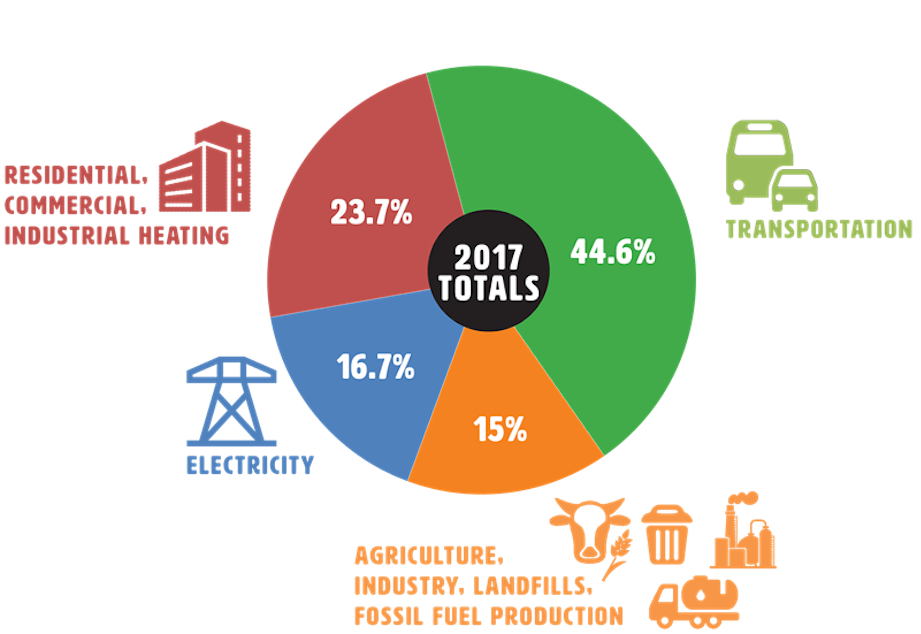

Washington’s automobiles, planes, ships and trains inflicted the most harm on the climate in 2017, as in previous years.

“What we do not have yet is an aggressive proposal to reduce transportation pollution,” Inslee said. “This is our big hole.”

Sponsored

Since the state’s last inventory, for 2015, emissions from jet planes have surged past diesel engines to become the state’s fourth-biggest source of climate pollution, following gasoline engines, natural gas and coal-fired power.

Coal emissions dropped 14 percent, while emissions from natural gas and jet fuel each swelled nearly 20 percent.

Sponsored

Since Inslee became governor in 2012, the state’s overall carbon emissions have gone up 6 percent.

"This should be cause for a three-alarm fire,” climate activist Emily Johnston with 350 Seattle said. “We should all be running around saying, ‘Oh my God! What can we do? What can we do?’”

“The next time the governor or another WA politician brags about our ‘leadership’ on climate change, remember that the data tell a different story,” Todd Myers with the conservative Washington Policy Center tweeted.

The state’s emissions have grown more slowly than its population or economy.

“The good news is that we are seeing that we can stop the growth of emissions — without putting the brakes on our economy,” Ecology director Maia Bellon said in a press release.

Sponsored

“The physics and the climate don’t care about our economy, don’t care about our population,” Johnston said. “The emissions simply need to come down.”

Sponsored

Climate science and state law have long called for steep reductions, not growth or stabilization, in our climate-wrecking pollution.

A 2007 executive order from Gov. Chris Gregoire requires Washington to reduce statewide emissions of greenhouse gases to 1990 levels by 2020, 25 percent below 1990 levels by 2035 and 50 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.

“We’re not on pace to hit the 2020 target at this point,” Ecology spokesperson Andrew Wineke said in an email.

He said the closure of two of four coal-burning power plants in Colstrip, Montana — where Washington's largest utility, Puget Sound Energy, gets much of its power — at the end of the year would help bring Washington within “a few percent” of the 2020 mandate.

Inslee faulted lawmakers who have rejected many of his proposals over the years, from a carbon tax to a requirement for low-carbon fuels.

Sponsored

“I’ve done everything humanly possible in this regard,” he said.

Inslee’s presidential platform this year called for much more ambitious pollution reductions nationwide than he has pursued in his own state.

Before the Inslee campaign disbanded in August, it publicized detailed policy proposals aimed at cutting the nation’s carbon emissions in half by 2030 and eliminate them by 2045 — reductions largely in line with what climate scientists say will be needed to keep global warming from reaching catastrophic levels.

As governor, Inslee has only aimed at stabilizing his own state’s emissions by 2020 and cutting them 25 percent by 2035.

Inslee successfully pushed a raft of new policies with the latter goal through the state legislature this year. He touted those on the presidential campaign trail as evidence of Washington state’s leadership on climate change.

Sponsored

On Tuesday, he told KUOW the state needs to aim higher.

“The science has ramped up our timeline within which to act,” Inslee said. “That’s why our state needs to up its goal, not only [meet] the one we’re not meeting now, but we need to up that goal.”

The Ecology Department said Tuesday it will announce more ambitious policies by the end of the year.

Johnston said the increasing attention some local politicians and leading presidential candidates are paying to more aggressive proposals on climate change, like the green new deal, gave her hope things can improve.