Seattle's first affordable housing high-rise tower in 50 years welcomes its first residents

This week, people who used to live outside began moving into a new building on First Hill. It’s the first new affordable housing high-rise tower Seattle has seen in 50 years.

It represents a different approach — in terms of scale and strategy — for addressing homelessness in the region.

Kevin Thomas Kiso smiles in a sunlit lobby, inside a concrete, steel and glass high-rise apartment building on First Hill. He has just finished signing his lease, and now holds a new set of keys.

“This is the coolest day of my adult life, and I’m 57 ... I spent 20 years sleeping right out here, at the Stimson Green Mansion by the park … the mansion over here," Kiso says as he gestures out the window. "I spent 14 years in my sleeping bag, with my laptop here. And then I would go to the library and read French literature, like Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean Paul Sartre, and Camus.”

Reading the French Existentialists helped Kiso get through a dark time in his life. He got addicted to heroin and spent time in prison. He’s been trying to stay clean ever since. For the last two years, he’s been living in a cubicle at a Salvation Army shelter.

“It was people milling around, and walking by, and rapping, and singing, and talking, and yakking, and you never got a moment of peace and tranquility," Kiso said of living on the street. "And I know that that’s what I’m being granted here. And silence is going to be kind of frightening at first for me, I believe. The tranquility and … I’m not sure how I’m going to react without sirens blaring and incessant traffic and things telling me to walk and don’t walk."

Homelessness is a problem with many faces. There are people who need help getting off the streets, and there are many people on limited incomes who need affordable housing, so they don’t get pushed into a cycle that can lead to homelessness. Experts say you have to work at the problem from both directions. The 17-story apartment tower in First Hill is therefore divided into two parts, each with its own entrance and lobby.

Sponsored

The bottom part is called "Blake House." It provides "permanent supportive housing" for seniors and veterans coming out of homelessness. It's run by a nonprofit called Plymouth Housing.

The top part is called "The Rise," and it’s for people on modest incomes, such as teachers, nurses and other health care workers. Another nonprofit, Bellwether Housing, runs this portion.

Kiso is part of the first cohort to move into Blake House. In a few months, he’ll have 112 new neighbors. Above Blake House, another 250 families will live in the Bellwether Housing section.

The tower has a common area lounge with a view of the First Hill neighborhood, including its many hospitals. Paul Schumann uses the lounge as he studies from a medical textbook on his laptop. He moved into this top part of the high rise in March.

Sponsored

"It's great," he says. "Being a part-time student, having very little income, needing to be close to both the hospitals and campus, was all something this building could offer. And really, everything else in this area was twice, if not more, the rent.”

An unusual situation

This high-rise tower wouldn’t have been possible without an unusual situation. Years ago, Sound Transit planned to put a light rail station here, on First Hill. That station was axed to save costs and Sound Transit was left with surplus property on its hands.

By law, the agency has to offer 80% of its surplus land to affordable housing providers, often at steep discounts, or in this case, for free. But even with that gift, to make a project work financially on this property, those affordable housing providers would have to build a high rise. And that’s something no nonprofit was big enough yet to tackle. So Plymouth Housing partnered with Bellwether Housing.

Sponsored

“It worked really well,” said Susan Boyd, CEO of Bellwether. “As we’re thinking about densifying the rest of the city — where we’ve got high-rise zones going up in the University District, in Northgate — I imagine that we’re going to have to do more of this.”

The federal government stopped funding affordable housing high rises in Seattle over 50 years ago. Nonprofits like Plymouth and Bellwether sprung up in the early 1980s to take up the slack. It’s taken them decades to get big enough to do what the Feds used to do locally.

“We’ve done this," Boyd said. "We know what it looks like, we know what it feels like, it’s not scary. The funders trust us to do it now.”

This model — where two nonprofits partner to build something big — could be repeated as Sound Transit expands and has more surplus land to get rid of.

Al Levine is the former deputy director of Seattle Housing Authority. He’s more cautious about this approach. He says it’s important to understand that free land from Sound Transit isn’t really free.

Sponsored

“Let’s call it what it is: Transferring the cost of affordable housing from affordable housing developers to Sound Transit," Levine said. "Is that the right thing to do from a policy perspective? Probably not, really. Sound Transit’s dying, dealing with costs. Not dying, literally, but Sound Transit’s burdened with costs that everybody and their brother is putting on them. You know, Sound Transit could have fixed a hell of a lot of escalators with that money.”

Levine argues that relying on Sound Transit for land is an example of the uncoordinated way that the government funds affordable housing in our region.

“There’s not a lot of strategic thinking in terms of 'here’s our resources, here’s how we’re gonna deploy them.' It’s pots of money people are chasing.”

But Levine says that in this chaotic environment, housing providers need to take whatever opportunities they can to make projects like this pencil out.

And those pots of money are growing bigger, including developer money from Seattle's Mandatory Housing Affordability program, and a bigger housing levy on the horizon. There is also more federal money, and a billion more dollars from state lawmakers this legislative session. On top of that, there is private philanthropy.

Sponsored

"I've never fobbed before"

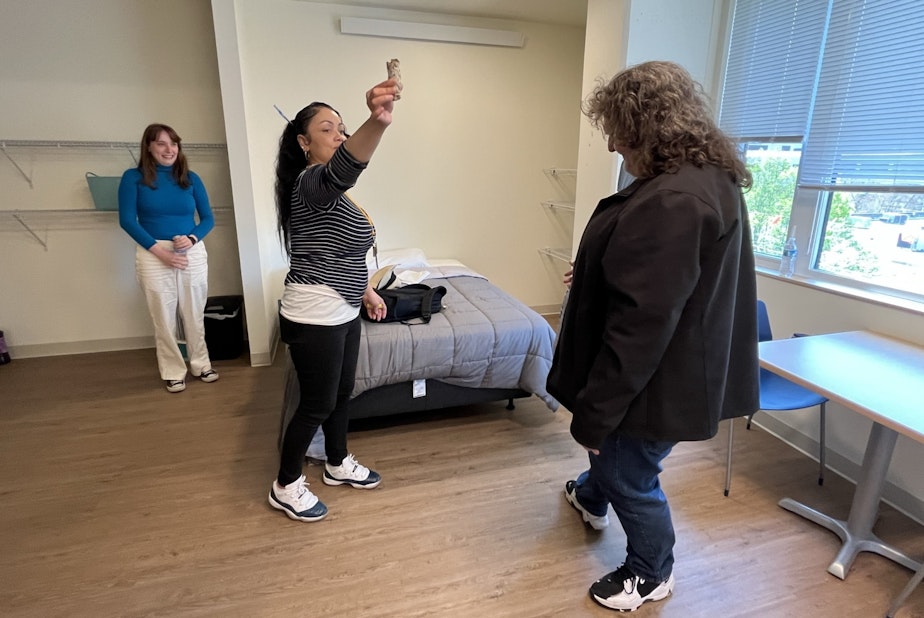

Back at Blake House, Plymouth staffer Philip Seymour leads Kevin Thomas Kiso up to his new apartment. So many things are new — a garbage chute, a key fob to operate the elevator.

"I've never fobbed before," Kiso says.

The hallway on the floor is wide enough for walkers and wheelchairs to pass each other.

“Your laundry room is right here," Seymour points out. "And this is your home."

“Let’s do this,” Kiso says, reaching for the new keys around his neck.

The door swings open, and he gasps.

“I didn’t expect this," he says, circling the bed with its tight, clean sheets and bedspread. "I thought I would go to Goodwill and just grab a mattress perhaps, and just throw it in a corner. But I didn’t expect a bed, with a real, professional hotel type...”

Here, his words fail him.

Plymouth staff shows him how to operate the kitchen equipment. The stove is on a timer, the water's controlled by a push-button switch. They open the cupboards, revealing a small care package of food inside.

“Hey!" Kiso exclaims. "Coffee! Top Ramen! My favorite! You — how did you know?”

Kiso is introduced to his case manager, told about onsite nursing staff, upcoming shopping trips for supplies, and taco nights.

“Do you have any other questions on how anything else in here works?" asks Plymouth staffer Seymour.

“I only have thanks and gratitude," Kiso says. "You know … I feel like the sun right now, and you’re all kind of orbiting around me. And I feel kind of demure, and I can’t express how I, I mean, I could take my clothes off and jump around, and that would truly be my happiness. But I won’t do that!”

“Well, do that when we get out of here, because this is your apartment,” Seymour says.

This affordable housing tower in Seattle's First Hill is just one building, but it’s a big one. And it could open the door for more buildings like it.

May 8, 2023, 2pm update: Sound Transit spokesperson David Jackson has clarified the rules around the agency's disposal of surplus land.

"By law, Sound Transit has to offer 80% of its surplus land to affordable housing providers, and Sound Transit has the ability to discount the price of that land," he wrote. "Sound Transit almost always offers its surplus land for free or at a steep discount when it will be used for affordable housing. This project was the first time Sound Transit discounted property down to $0, so it was a milestone under the statute. "

The story has been updated.