Seattle's queer history: Out from the underground

A classic brick building sits at the corner of Cherry Street and First Avenue in Pioneer Square. It's attractive but unassuming, with a coffee shop and bookstore among its occupants.

Passersby may not guess that it also holds a special place in Seattle's history.

Take a few steps below street level, through a set of doors thrown wide for visitors, and you'll find yourself inside what was once the city's first gay community center. It's now home to Beneath the Streets, known for its underground history tours. And in the summer, it's the first stop on a walk through Seattle's queer legacy.

As tour guide Terrilyn Johnson explains, this section of Seattle sits atop a network of tunnels that were once city streets. Seattle was first built at sea-level and had to be raised in the late 1800s to avoid flooding. New streets were literally built on top of old ones, creating a maze of underground chambers.

"When they created the underground, they unwittingly created safe spaces for queer people," Johnson said.

Sponsored

Parts of these tunnels became hideaways for the LGBTQ community. Like the community center, which was below street level, its windows barely visible to passersby to protect the identities of those inside.

Though Seattle is largely welcoming to queer people today, some of the city's earliest policies targeted LGBTQ people, prompting many to lead double lives.

"Even early on as a logging community, the city powers knew that there were gay people here. They started putting together sodomy laws in 1893," Johnson said. "And even though sodomy can be applied to any two people having sex without the intention of having children, it wasn't like they're going after any heterosexual couple that had no children. It was expressly going after the non-gender-conforming folks."

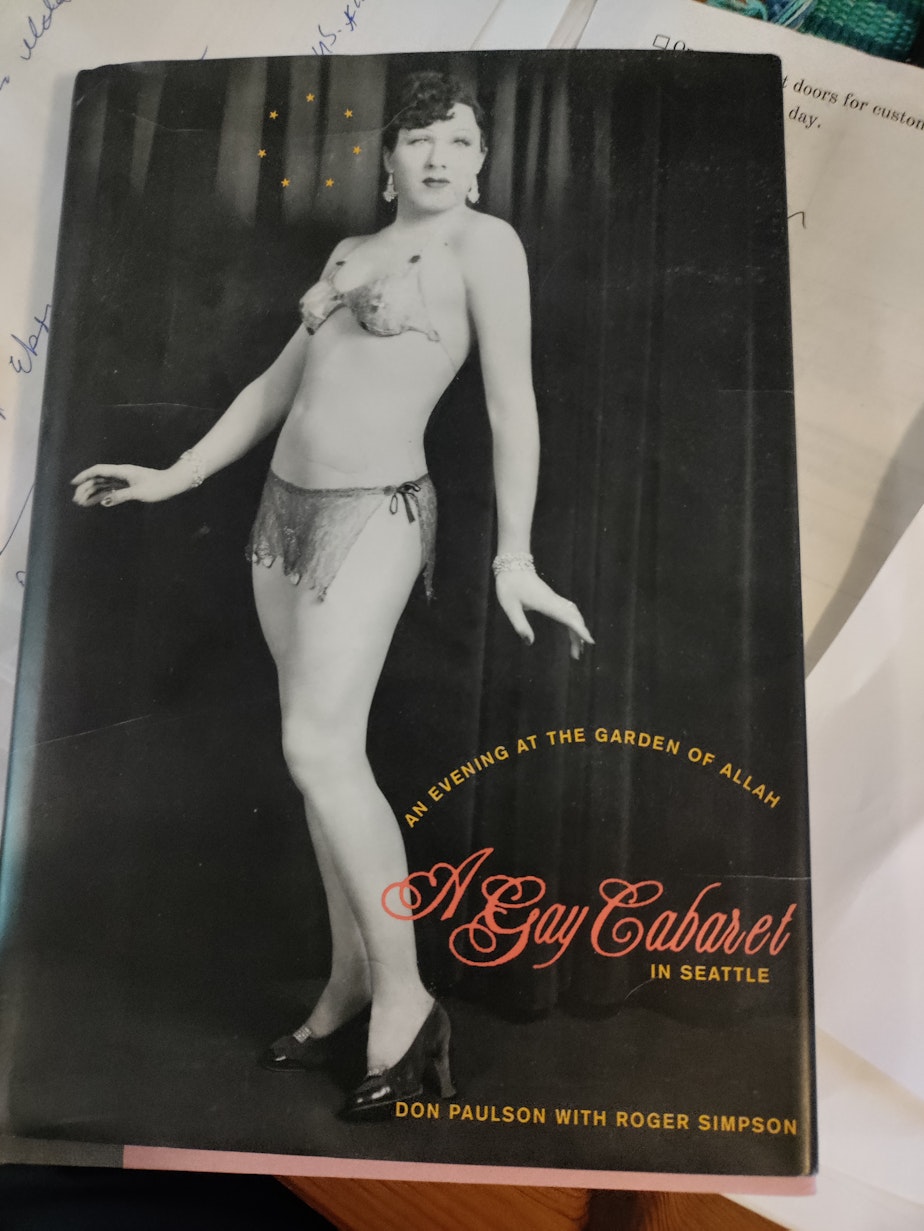

Despite its discriminatory laws, Seattle's LGBTQ community flourished, especially in underground spaces. One of the first gay-owned gay bars in the United States, the Garden of Allah, opened in 1946 in the basement of the Victorian-era Arlington Hotel in Pioneer Square. Johnson said it was known for its spectacular drag performances. And customer anonymity was a top priority.

But the establishment soon drew ire from the U.S. Navy. Servicemen were frequenting the gay cabaret venue, and the Navy eventually caught on to what the club and its recruits were up to there.

Sponsored

"Then, [the Navy] realized there might be some other [gay] bars," Johnson said. "So, they diligently researched all of this, and they put together a list — gosh darn it — of bars that they were banned from. And the queer Navy boys were like, 'Oop, thank you very much," and that was their guide.”

During World War II, queer women joined the scene too, thanks to the need for factory workers. Johnson noted they were allowed to live together, ostensibly, as roommates. They found community at gay and lesbian establishments like The Casino, located down a flight of stairs under a marquee that still reads "Casino Dancing." It later became known as Madame Peabody’s Dancing Academy for Young Ladies or, simply, The Dance.

The Dance was one of the few places on the West Coast where same-sex dancing was allowed, according to the Northwest Lesbian and Gay History Museum Project.

When the war was over, people didn't want to leave. Instead, many stayed and laid the groundwork for what Johnson called "this queer Mecca" in Seattle.

Sponsored

LGBTQ people still weren't entirely free to be themselves, though. So they found ways to preserve the spaces they'd created.

Bars and clubs would pay off police, who in turn would provide security at the doors of queer establishments — a tradition dating back to the late 1890s, particularly during the Prohibition era, Johnson said. If you didn't pay, Johnson said, officers might raid a bar or harass patrons; it was a double-edged sword.

By the late 1960s, the community was starting to activate.

Places like the gay community center, where Johnson begins the queer history tour, enabled early conversations about how to change the status quo. Stonewall happened in 1969. LGBTQ people were fighting back against discrimination. Attitudes were changing.

Sponsored

Seattle saw its first Pride parade in 1974, according to Seattle Pride. It wasn't actually recognized by the city and included fewer than 200 people.

By 1977, the first official parade welcomed about 2,000 people and kicked off the city's first “Gay Pride Week.” A year later, voters overwhelmingly rejected an initiative to roll back protections for LGBTQ people.

In 1992, the Pride parade was expanded to include bisexual and transgender identities. The Seattle Pride Parade is now one of the largest in the country.

Sponsored

Johnson said she wants LGBTQ people to continue to see Seattle as a safe space and come here to find community.

"But I also want this to serve as the center of the ripple that spreads outwardly, so this is normal," she said. "We're all human. We all love, and we should all be able to love who we want to love."

According to the Human Rights Campaign, state lawmakers adopted 70 anti-LGBTQ laws just in the first half of this year. They include 15 laws banning gender-affirming care for transgender youth and two targeting drag performances.

Transgender people, in particular, are targeted by the far-right.

Marsha Botzer is all too familiar with their tactics.

Botzer founded Seattle's Ingersoll Gender Center in 1977. It provides support for transgender and gender-nonconforming people and is one of the oldest such organizations in the country — thus earning its place on Beneath the Streets' queer history tour.

"The old ghosts are rising up against us again," she said. "But when we gather together and support each other, that's the key...that's how we keep going. That's how any group can survive, thrive, and grow."

Botzer said Ingersoll has taken on many forms over the years, just as their opponents have. She said the far-right threat is different today only in how it's dressed up; the far-right's "fears, misconceptions and concerns" are the same as they've always been.

The internet and social media have made it easier to spread extremist views. But Botzer said those advances have also made it easier to connect the LGBTQ community, and that can make all the difference for those who feel alone in places where their rights and safety are being threatened.

"It's not easy to take the first steps, unless there's some support," she said. "The reason for Ingersoll is to be there for folks contemplating that first step."