Seattle could do more to counter rise in sophisticated retail theft, report says

A Seattle City Auditor's report states that the city could "do more to tackle organized retail crime," such as using online video.

“One of the things that we learned is that a bottle of perfume may be stolen in North Seattle and within 24 hours, it is on a shipping container destined for sale overseas,” researcher Claudia Shader told the City Council's Public Safety and Human Services Committee Tuesday morning.

Shader wrote the auditor's 43-page report on organized retail theft. It was produced at the request of City Councilmembers Lisa Herbold and Andrew Lewis.

RELATED: Washington AG forms task force to tackle organized retail theft

One idea Shader presented to the council committee is to allow victims to report theft over a system like Zoom or FaceTime, rather than waiting for a patrol car to show up.

Sponsored

Known as “Rapid Video Response,” police in Kent, England, found that this system was 656 times faster than sending a patrol officer to the scene to take a report, according to Shader.

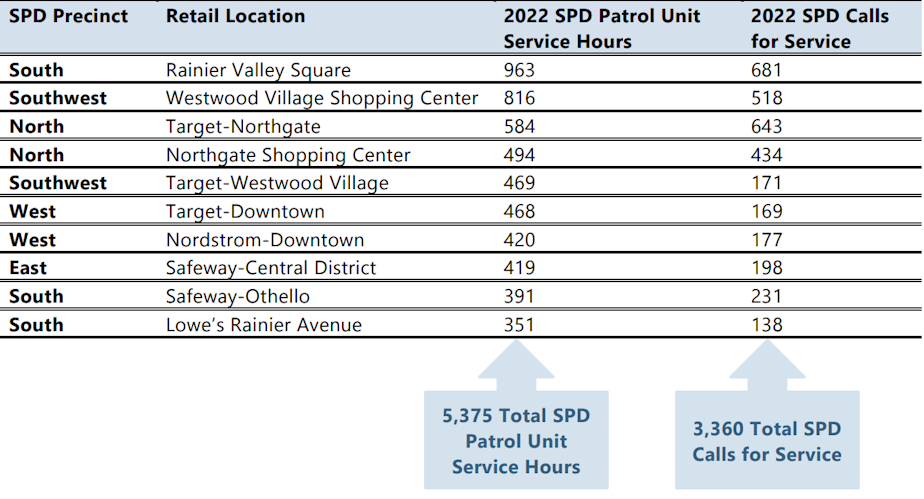

Last year Seattle police responded to more than 13,102 calls from retailers, which took a combined 18,615 hours of time — the equivalent work of nine full-time Seattle police officers in a year. Shader said a video system would be more efficient.

Organized retail theft in Seattle

The audit primarily focuses on "fences." It makes seven recommendations for city leaders to consider (see a full list of recommendations below).

Sponsored

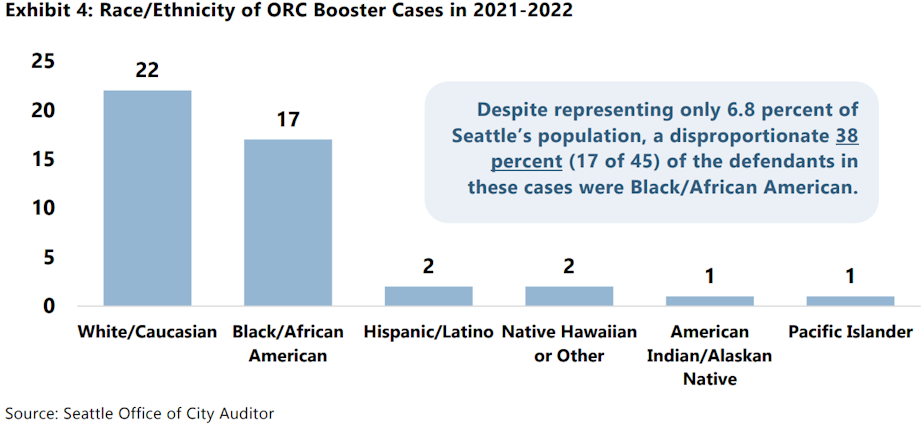

The report points out that organized retail theft is more "sophisticated" than simple shoplifting, and utilizes an underground supply chain, targeting high-demand products. The operations generally break down into "boosters" and "fences." A fence is a person who sells stolen goods and a booster is a person who does the actual stealing from stores.

Fences provide boosters with lists of items to acquire and pay them to steal. Boosters can be equipped with special clothing to hide stolen items, or high-powered magnets to counter anti-theft devices, or shopping bags modified to get around door alarms (such as aluminum foil on the inside). Or a booster could simply fill up a shopping cart and make a run for it out the door.

RELATED: Seattle, King County prosecutors will partner on organized retail theft

The report notes that fences target people experiencing homelessness or those with substance abuse disorders to act as boosters. Undocumented immigrants are also a source of forced booster labor in this underground market, often as a means to pay off debts.

While speaking with the council committee Tuesday, Shader suggested the city collaborate more with state and federal agencies that can help Seattle tackle the problem. The audit also pointed to other city efforts to address the underlying causes of crimes like shoplifting, such as a new program to reward people for not using drugs known as “contingency management.”

Sponsored

According to the auditor's report:

"Fencing operations can be simple or operationally complex. Low-level fences, or 'street fences,' will sell the stolen goods directly to the public through unregulated street markets, flea markets, swap meets, or online. Boosters may also sell the merchandise to mid-level fences who run 'cleaning operations.' Cleaning operations remove security tags and store labels and repackage stolen goods to make them appear as though they came directly from the manufacturer. This cleaning process may even involve changing the expiration date on perishable goods, which creates public health and safety concerns. The 'clean' goods may then be sold to the public or to higher-level fences, who operate illegitimate wholesale businesses. Through these businesses, the fences can supply merchandise to retailers, often mixing stolen merchandise with legitimate goods. In addition, fences selling goods via online marketplaces, or 'e-fencing,' may ship stolen goods across state or national lines. E-fencing is more profitable than fencing at physical locations."

RELATED: SPD’s roving unit shifts focus from 'hotspots' to retail theft

The National Retail Federation points to this system as the reason organized retail theft rose by 60% between 2015 and 2022. In 2020, Seattle ranked 10th in the United States for this type of theft, and eighth in 2021. The Washington Retail Association says more than half of the state's retailers have reported $2.7 billion in losses over the past year.

Sponsored

There are seven recommendations that the auditor's report presents for city leaders to consider, including:

- Support City participation in collaborative efforts among agencies, including collaboration with the new Organized Retail Crime Unit in the Washington State Attorney General’s Office.

- Leverage federal and state crime analysis resources.

- Use in-custody interviews of “boosters” — people who steal on behalf of fencing operations — to gather information on fencing operations.

- Explore new uses of technology to address organized retail crime.

- Use place-based approaches to disrupt unregulated street markets.

- Follow the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office “prosecution checklist” for cases that involve organized retail crime.

- Consider City support of legislation that addresses this type of crime.