Officials say they're fighting crime in this district. Seattle's Little Saigon is fighting for its 'legacy'

Lunar New Year festivities turn Seattle's Chinatown-International District into the community Tanya Woo remembers growing up in — long before the Covid-19 pandemic.

The mood is festive, she says, punctuated with firecrackers and splashes of red for good luck. There's food and dancing and something else, something she misses: people. Lots of people.

Woo says the Lunar New Year celebrations earlier this month brought good business to the community. People ate and shopped and enjoyed performances like they did before the pandemic.

There will be more events in late April, when the CID will officially hold its festival. It was delayed because of the spread of the Omicron variant of Covid-19.

With Lunar New Year, and subsequent days of celebration, now over, Woo says it's much quieter again. Except for activity "bleeding" from the corner of 12th Avenue South and South Jackson Street.

Crime has risen across Seattle; overall, it was up by 10% last year compared to 2020, with violent crimes like robbery and aggravated assault up 20% .

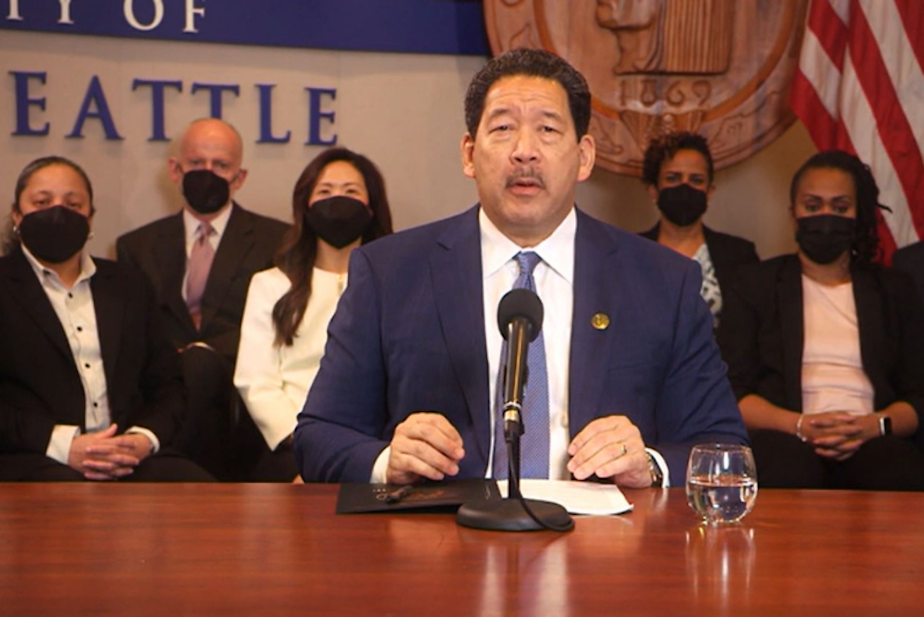

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell — who took office in January — says he has a plan to stop it. He's directing Seattle police to focus on what he calls crime “hotspots,” like Little Saigon in the Chinatown-International District. He also has plans to hire more police officers.

Sponsored

"Working with the community, including the restaurant and shop owners of Little Saigon, our police officers in the first 21 days of January made 23 felony arrests, 14 misdemeanor arrests" and recovered stolen property, Harrell said during his State of the City address.

But is that the right approach? Woo doesn't think so.

Rather, volunteers like her have turned to the CID Community Watch to offer help to those in need; the Community Watch was founded in 2020 amid a rise in anti-Asian attacks.

"We saw a lot of gaps in services that were being offered to the Chinatown-International District, and we felt like we could do something as an alternative to policing," she says.

Sponsored

Woo patrols the neighborhood with other volunteers on Saturday nights. They're armed with little more than basic CPR and de-escalation training as well as Narcan in case they come across someone who is overdosing on narcotics.

While hardly adequate to address all the needs of the people in the CID, those tools have come in handy for the Community Watch.

They found a man unconscious last week. Woo says they later found out he had overdosed. Community Watch volunteers called for help and started CPR while they waited.

"He looked like he could've been my friend's dad; he did not look like the stereotypical drug-user," she says of the man. "People are buying drugs at 12th and Jackson, and coming to Chinatown and Little Saigon and Japantown to die."

And the community is simply not equipped to help everyone.

Sponsored

Woo points specifically to a lack of social workers and shelter beds. Volunteers have walked the neighborhood with food and water in tow, or tried to find people a bed to sleep in rather than a tent — or less — on the street.

She recalls times when a police response did not seem appropriate, especially in cases when she suspected a mental health issue was at play. But in many cases, police are all city operators could offer her. Woo is left feeling helpless.

"If you drive by [12th and Jackson], you can see that they may be doing drugs, but they're also in a lot of pain," she says. "Just getting them the help that they really need, I think, will really help [the entire neighborhood]."

While the Community Watch volunteers do what they can to keep crime at bay, business owners have had to get creative, too.

They leave their empty cash registers at their doors, Woo says, signaling to would-be thieves that there's nothing worth breaking in for; that doesn't always work.

Sponsored

Woo is sad to see the CID like this. She grew up there and now runs her family's business. They restored and reopened the historic Luisa Hotel in 2019 — which Woo says was also the last time it was fully leased.

But it's not enough that neighbors are looking out for each other and doing what little they can to solve problems that reach beyond the CID.

"Culturally, we don't want to create waves," she says, noting the CID is largely an immigrant community where people may not speak English well, if at all. "So, we're not seeing a lot of people making reports or seeking help when they need it."

They feel ignored by the city.

The situation has gotten worse in the last month, but it has been developing for years now, fueled by Covid-19 and the anti-Asian hate that followed it.

Sponsored

"The pandemic has not been kind to our community," she says. "There has just been a lot of fear and not a lot of trust."

Still, Woo encourages people to visit the CID and support the businesses that are trying desperately to stay open.

Woo says it's about more than the bottom-line for them: It's about their "legacy of community-building."

She hopes 2022 — the Year of the Tiger — will be a meaningful year for the district.

"It's a new start, a fresh start," she says. "[We're] bringing in the spirit of the tiger."