Remembering the intellectual clarity of the late Beth Bentley's poetry

Each day during the month of April, KUOW is highlighting the work of Seattle-based poets for National Poetry Month. In this series curated by Seattle Civic Poet and Ten Thousand Things host Shin Yu Pai, you'll find a selection of poems for the mind, heart, senses, and soul.

The following contains short recordings of Beth Bentley's poetry being read by family, former students, and fellow poets.

B

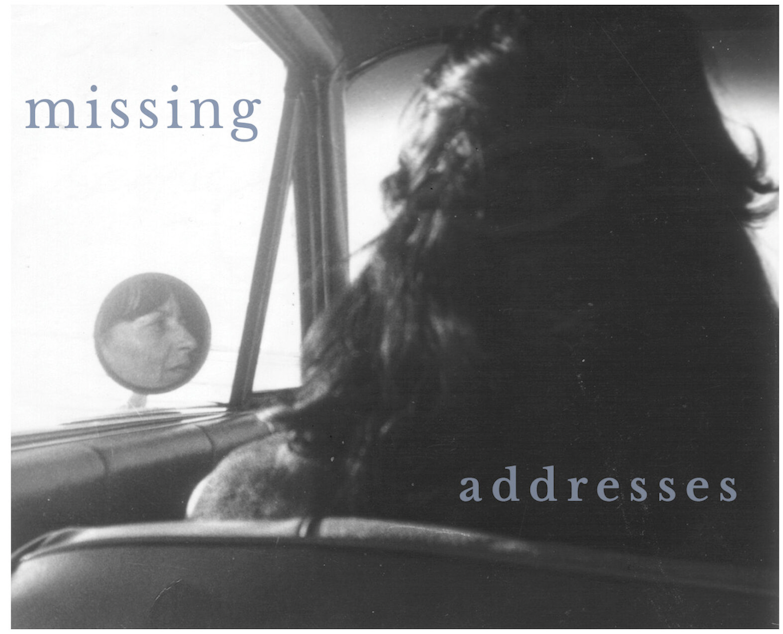

eth Bentley was a teacher and poet who, along with her husband — poet Nelson Bentley — left an indelible mark on Seattle's literary scene. When she died in 2021, she and her son Sean Bentley were working on her final poetry collection, titled "Missing Addresses," which is set to publish this month.

Pai spoke with Sean Bentley about his mother's influence and legacy.

Sponsored

"I would say it was an unusual childhood by any measure," he said. "We had faculty parties where the entire house would be filled with writers, poets, whether they were students or faculty. I remember various folks who were rolling into town on reading tours and such."

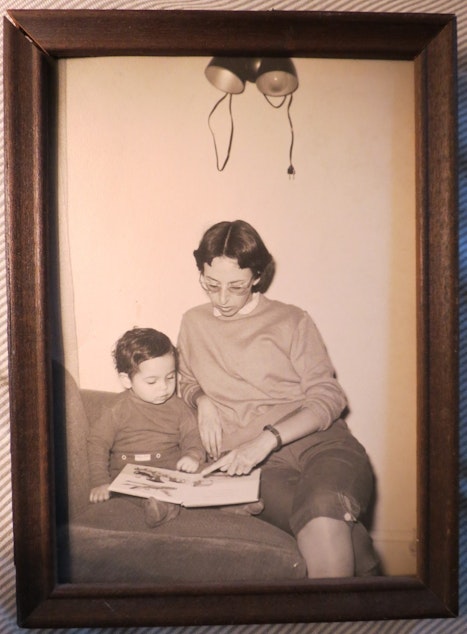

Life in the Bentley household was literary by every degree imaginable. Books and poetry were the hub of family life, something that manifested in Sean, who became a poet himself. He said they both shared a "deep intellectual spirit of discovery," from admiration of Umberto Eco to various philosophies and philosophers.

Mercedes Lawry reading "Dying in Paris"

Indeed, Beth's poetry is defined by an intellectual examination of the interior of the human experience, something her students remember about her from when she taught at Bellevue Community College.

Sponsored

"I'm always amazed by how her work connects everyday experiences to the wellsprings of art and philosophy," said Eileen Walsh Duncan, who was a student of Bentley's in 1989.

Eileen Walsh Duncan reading "The Pastry Maker"

"I think what she would have hoped she taught them was how to think outside the box of yourself, to be able to put yourself in the mind of another person, another time — to think deeply," Sean said. "To make associations so that whatever you're writing about, you'll have more than one level, it will be itself and it will be illuminating another set of issues."

Beth and her husband Nelson were cut from a different kind of poetic cloth. Nelson taught a poetry workshop at the University of Washington and had a clear renown — Sean said his father had a following of students that spanned decades. His poetry was more personal, humorous, and quirky.

Sponsored

"She spent more time writing than teaching," Sean said.

Daphne Davies reading "Light in Autumn"

Those differences drew different recognitions to the Bentleys. Beth was constantly sending poems to magazines, which drew an intellectual crowd that later waned as cultural tastes in poetry shifted. The tenor of her work eventually changed too, from more personal reflections on raising a family to broader themes of memory, her Jewish upbringing, and relationships at large.

"Poetry itself was becoming less formal and more confessional, and she just felt like she was too old-fashioned," Sean said. "Attached to that, she felt like she was growing too old, that all these young whippersnappers reading poetry...she just thought, 'I've got too many miles on the odometer.'"

Sponsored

Julian Edelman reading "Old Jewish Cemetery, Prague"

Beth's posthumous collection tackles her feelings of being an outsider, from being Jewish in a Christian world, an intellectual in an unintellectual culture, and being a woman in a male-dominated industry.

"If there are readers who might identify with the notion of being underappreciated, or at some kind of a remove from the mainstream, it might be worth taking a look at her work," Sean said. "It's very moving."

Lynn Miller reading "Nevertheless"

You can listen to the full interview with Sean Bentley by clicking "play" on the audio above.