Remembering 'the cow that stole Christmas,' 20 years later

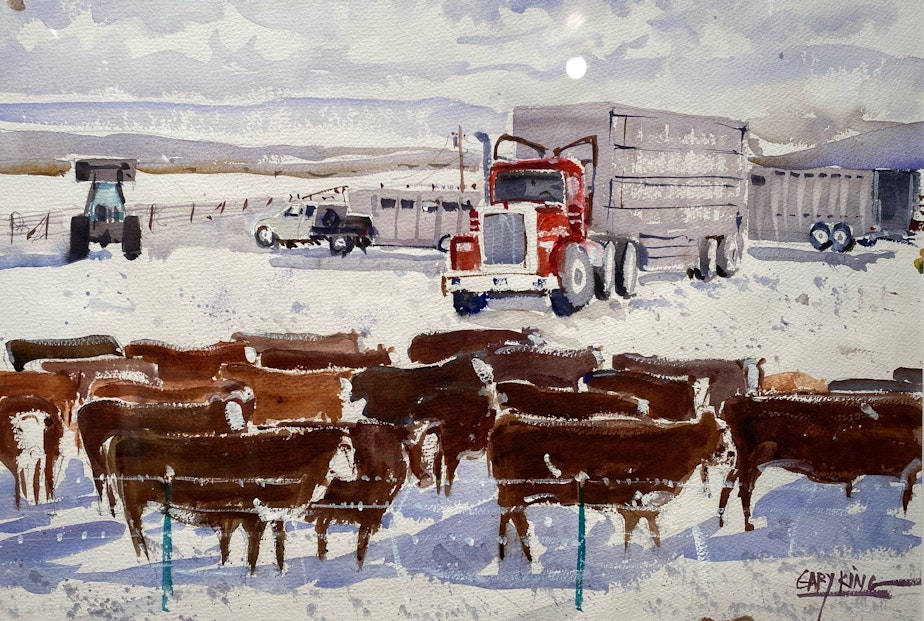

Twenty years ago, on Dec. 23, panic descended on Central Washington and the nation’s cattle industry over a single cow.

U.S. Department of Agriculture officials announced a Washington state dairy animal had tested positive for Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy — also known as BSE, or Mad Cow Disease.

Today, many locals in Mabton know this event as, "the cow that stole Christmas."

A single case of mad cow disease in one of the biggest beef-producing states, in the biggest beef-producing country, sent regulators and the industry on a frantic search. Regulators needed to track down where the cow went after being slaughtered — and find any other animals that may have had contact with it — before they showed up in the food supply.

It's a time that Northwest News Network's Anna King remembers clearly.

"Somebody came to my desk and handed me this piece of paper that had just come off the wire, it was probably still warm," King said. She was at the Tri-City Herald, and would soon be driving out to nearby Mabton. "And basically, it said there's been a 'mad cow.' And it's been discovered, not only in the United States — which was the first time ever — but it's been discovered in our backyard."

Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) is a prion-based disease that attacks a cow's brain and nervous system. Cattle with BSE often struggle to stand or walk, lose weight, and struggle to produce milk. The disease is fatal, and cattle who contract or are suspected of exposure to BSE are euthanized to prevent the animals' suffering and further spread.

It was long believed that humans couldn't contract mad cow disease, but in 1995, three victims of a new variant died in the United Kingdom. After that, research into the disease intensified. In 1997, the Food and Drug Administration banned "ruminant feed," a common protein-based feed, after it was found to cause BSE.

Sponsored

"What had happened is that they were feeding cattle parts like bone meal and protein meal. So it was actually like cattle eating cattle," King said. "That had been banned in Canada, but not before this particular animal had received some of that feed."

"The cow that stole Christmas" was a Holstein dairy cow born in Canada in April 1997, four months before the ruminant feed bans in Canada and the United States. The cow had spent years at a Washington dairy farm and had two calves before it tested positive for BSE.

"The scramble was on to figure out what had happened after that," King said. "Had this cow gone into the food chain? Had its calves gone into the food chain? Where had it moved throughout its life? There were just so many questions, and we were trying to take one at a time and run it down to ground."

The announcement of the first case of classical BSE in U.S. history sent the industry into chaos. More than 30 countries immediately shut their borders to American beef. Dozens of USDA agents went farm to farm throughout Washington, and around 700 animals with potential exposures were "destroyed."

Luckily, the cow and its calves hadn't made it into the food supply, and in the end, no cases were found outside of the single Holstein, and no cases jumped to humans.

Sponsored

What's changed, 20 years later?

As was the case in 2003, cattle today frequently move across state and international borders from birth to slaughter, with regular exposure to other cattle at public livestock markets.

Washington state veterinarian Amber Itle said that today, a shift to electronic IDs is being done to speed up commerce, limit costs to farmers, and improve cattle traceability. In the case of an outbreak, that system is designed to remove much of the guesswork required in 2003.

"If that animal has an electronic ID applied on the farm, the birth premises, we know where she started," Itle said. "Maybe she got a brucellosis vaccination, and that's how she got her tag, maybe the veterinarian applied a tag, maybe the producer applied that tag — that official tag is that individual identifier that's unique to that animal. Think about it like a license plate in a car."

Much of the market has still been rebounding from the initial shock of 2003, and Itle said that despite pushback from some in the industry over the cost of tags, or hiccups in commerce due to extensive tagging, outbreaks can be more effectively mitigated.

Sponsored

"These steps seem small, and for some people they might even feel like a burden," Itle said. "But if we do get a disease here, it's really the only way that we can keep people in business, right?"

The state still regularly tests for BSE, but a mad cow outbreak is of minimal concern in comparison to more widespread diseases like the ongoing avian flu epidemic, or foot and mouth disease (which was eradicated in the U.S. in 1929).

"I don't know that BSE really even registers on my radar of concern," said Ryan Scholz, the Oregon state veterinarian.

Scholz said there have only been six cases of mad cow disease in the United States since the first case in 2003. Outside of the Mabton Holstein, which was registered as classical BSE, all cases have tested as an atypical variation.

"And those you trace the cow back to its origin, and you look for the siblings and any offspring," Scholz said. "Which takes some work, but you're not worried about really finding more than just that one case."

Sponsored

For Dan Wood, executive director at the Washington State Diary Federation, the perception of the disease is also of concern. In Mabton, satellite TV trucks lined the streets, and caution over the food supply sent farms, restaurants, and markets spiraling. Some residents still call Mabton the "mad cow community."

"I think [perception] was the biggest concern 20 years ago. How do you assure people that everything is safe?" Wood said. "The public was not impacted. They had safe beef. And if it ever happens again, that will be the same outcome. The difference is going to be this time, we will end up slaughtering fewer unaffected animals."

While much of the industry has recovered since 2003, not every farmer has been so fortunate.

Twenty years later, Anna King managed to find Sergio and Rosa Madrigal, whom she interviewed during the 2003 mad cow hunt. The Madrigals had around 400 calves "destroyed" for their suspected exposure to the sick Holstein and her calves.

Sponsored

"We lost everything, you know, all this — we worked so hard for it, for so many years," said Rosa Madrigal, who helped to translate her husband's Spanish outside their old farm. "Now we don’t have anything. We don’t even have a place to live."

Without the calves, the Madrigals had to rebuild their farm from near scratch. Then, the 2008 financial crash came. By the time they'd weathered these two storms, the Covid-19 pandemic hit them with another round of setbacks.

"Whoever felt better had to come out and feed the animals," Rosa Madrigal said. "At the end, there was no help."

In December, the family was evicted from their farm. Sergio Madrigal is working in construction and farming, while Rosa Madrigal is a part-time caregiver.

"When you're on the edge in agriculture, and you don't have much of a safety net, it's really tough," King said. "Cattle are so volatile that the price fluctuates and goes up and down. And they just got sideways with their farm."

Outside their former farm, the Madrigals held back emotions when reflecting on the events from 20 years ago.

"There's stuff that you can't stop or predict," Rosa Madrigal said. "It's something that has to happen sometimes."

Listen to the full Soundside story by clicking "play" on the audio button above.