Kelp has protected Samish people for millennia. Now it needs their help

Kelp forests have fed and supported coastal tribes like the Samish since time immemorial. With these underwater forests in trouble up and down the West Coast, some researchers and tribal members are now trying to return the favor.

O

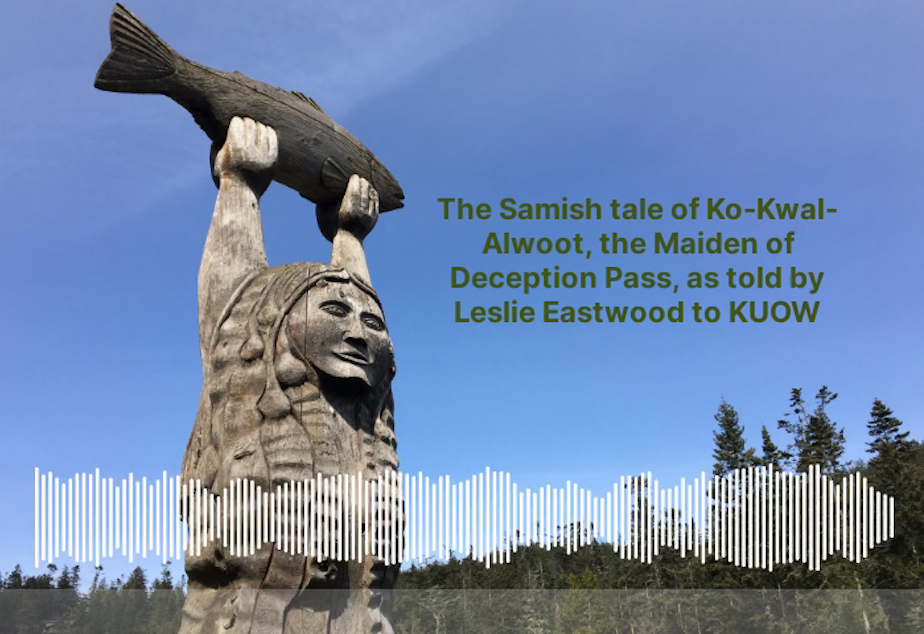

n a small peninsula jutting into the kelp beds of Rosario Strait, near Washington’s Deception Pass, stands a two-story cedar pole. A woman and a sea creature are carved on opposite sides. The long-haired woman and the kelp-covered creature are the same being: Ko-Kwal-Alwoot.

“She is an immortal being that watches over and protects all of our Samish people,” said Samish Indian Nation elder Leslie Eastwood, the tribe’s recently retired general manager. “We find evidence of her existence to this day when we come out to this very place at Rosario, look out across the water, and see the long ribbons of kelp in the water.”

The cedar pole, possibly the only monument to kelp in the Pacific Northwest, illustrates a defining story of the Samish people. Eastwood shared the story of Ko-Kwal-Alwoot on a sunny April morning as the tide went out at Rosario Head.

“A long time ago, there was a lovely village here next to Deception Pass at a place called Rosario,” her story begins. “There was lots of spring water, and the tide would go out far, and it was a perfect place for the people to be protected and be able to go out and gather shellfish.”

Sponsored

10 mins

Leslie Eastwood of the Samish Indian Nation tells the story of Ko-Kwal-Alwoot, the Maiden of Deception Pass, at Rosario Head in Deception Pass State Park.

10 mins

Leslie Eastwood of the Samish Indian Nation tells the story of Ko-Kwal-Alwoot, the Maiden of Deception Pass, at Rosario Head in Deception Pass State Park.

In the story, a young woman from Rosario was out gathering shellfish when she met and fell in love with the king of the sea creatures. At first, her parents refused to let them marry, angering the sea king.

“From that moment on, the fishermen would go out to harvest, and their nets would come back empty. Ladies would go out to gather shellfish for their people, and their baskets would come home empty.”

Eventually, with their village going hungry, Ko-Kwal-Alwoot’s parents relented.

“Ko-Kwal-Alwoot thanked her parents for being loving and understanding, and she said, ‘I will always make sure that there is plenty of fish for you. Lots of shellfish, lots of fresh water, and I will watch over you forever,’” Eastwood said.

Sponsored

“She went out to sea until all they could see was the long, flowing ribbons of kelp,” Eastwood said. “To this day, the Samish people truly believe that when we come out to this place, and we see the kelp ribbons there, that's a reminder to us of her devotion to her Samish people.”

In recent years, Samish fishermen and elders have noticed their kelp protector dwindling. Kelp forests in the San Juan Islands shrank by about a third from 2006 to 2016 and have fluctuated since then, according to studies of aerial photos by the tribe’s natural resources department.

“You used to be able to see hundreds of feet of beds of kelp, almost so thick that it would look like you could walk across it,” Eastwood said.

“We were having tribal elders tell us that they couldn't find kelp to cook their salmon traditionally or for other traditional uses,” Samish natural resources director Todd Woodard said.

“It's that linchpin of cultural use and cultural practices that we're trying to ensure can continue for the next seven generations and beyond,” he said.

Sponsored

Widespread loss of kelp beds elsewhere in Puget Sound has fueled concern as well. South Puget Sound has lost almost all of its kelp beyond the Tacoma Narrows, while bull kelp has disappeared from Bainbridge Island.

By contrast, kelp forests near the outer Washington coast appear to be thriving, according to the Washington Department of Natural Resources.

S

cientists confirm that kelp forests protect coastal areas by absorbing wave energy. Kelp also provides habitat for hundreds of species, including much of the seafood pulled out of Puget Sound.

Sponsored

The Indigenous-kelp connection likely goes back 17,000 years: Many archeologists now think Native Americans’ ancestors paddled here from Siberia along a bountiful "kelp highway," back when ice sheets still covered much of North America.

In March, Washington state established its first kelp conservation area near Everett and committed to protect or restore 10,000 acres of kelp and eelgrass in the next 18 years.

How to do that isn’t entirely clear.

Protecting an area from boat anchors or oil spills is one thing. But how do you protect kelp from a warming ocean? The big ocean heat wave known as “The Blob” caused widespread kelp dieoffs in 2014, 2015, and 2016 from British Columbia to Baja California.

“There's a lot of things happening [to kelp], and the science hasn't quite caught up yet with the why,” Woodard said.

Sponsored

Researchers in Washington and British Columbia have been trying for a decade, mostly in vain, to grow and transplant bull kelp — the only canopy-forming, or sea floor to sea surface, kelp in the Salish Sea — so it can survive and reproduce on its own.

These giant algae have complicated life cycles that researchers have struggled to mimic in the lab.

Unlike the centuries-old trees in a forest, even the tallest bull kelp grows from a tiny speck in less than a year, then dies back to be replaced by the next generation. In theory, fast-growing kelp forests can bounce back quickly if their environment allows it.

“We’ve tried a lot of things over the years,” Gray McKenna, a kelp specialist at the non-profit Puget Sound Restoration Fund, told the Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference.

Part of the difficulty is not knowing why kelp is dying in some areas but holding its own in others. That’s where people like Elise Foot Puchalski come in.

“I

love the ocean," said the 16-year-old from Edmonds. "And I’m really interested in scientific diving.”

Foot Puchalski is an experienced scuba diver and hopes to become a marine biologist.

“Not much is known about the ocean, and kelp forests are so important,” she said.

Foot Puchalski is part of a squad of volunteer divers that the Puget Sound Restoration Fund and the non-profit Reef Check are training to do kelp science underwater.

Off Camano Island, dive instructors with Reef Check trained the group of citizen scientists to take accurate measurements of rocks, algae, and animals, all while swimming in murky, 48-degree water. Reef Check has volunteers keeping tabs on kelp forests in California and Oregon and is now expanding the effort to Washington state.

“The most important tool for natural resource management is long-term abundance data, which is what we're doing here,” Seattle paralegal and citizen-scientist in training Chloe Carothers-Liske said while squeezing into her wetsuit for a training dive. “Without knowing what's out there, how can you make effective environmental policies?”

Besides, swimming in a kelp forest can be simply amazing, if cold.

“I'm not too bothered by the cold,” said Carothers-Liske, who describes herself as a polar bear.

“It's like you're walking through a forest, except for it's underwater,” Carothers-Liske said. “It's really, like, otherworldly to be in an underwater forest.”

T

he statue of Ko-Kwal-Alwoot looks out on traditional Samish territory, but those lands and waters don’t belong to the Samish. The land is mostly Deception Pass State Park, while the waters are owned by the state of Washington.

Despite being a signatory to the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, which took away two dozen tribes' lands in exchange for small reservations and fishing and hunting rights, the Samish Tribe never got a reservation to call its own. It has gained fewer rights than other Washington tribes have come to enjoy.

“Samish, due to a whole long history, doesn't have those fishing treaty rights,” Woodard said.

With the treaty signing, the Samish were supposed to move to other tribes’ reservations, but most Samish people refused, only to be pushed out by settlers eventually, according to a timeline produced by the tribe.

A century later, a clerk at the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs made a clerical error with dire consequences when she left the Samish off a revised list of federally recognized tribes in 1969. It took 27 years for the Samish to regain their federal recognition.

In the meantime, tribal members without land or opportunity dispersed, making the Samish an exceptionally urban tribe. One federal judge called them the cyber tribe.

To this day, the Samish lack the key treaty right most Washington tribes won with the historic Boldt decision of 1974: the right to half the fish and shellfish in their traditional areas.

Still, tribal officials say Samish people’s connection to their homeland and traditional foods like salmon and kelp has endured.

“The sense of place is still very, very strong,” Woodard said. “But there is not a sort of designated living community that's a Samish community like there are for other tribes with reservations.”

“Those resources such as salmon, shellfish, et cetera, are no less important to the Samish people than they are to every Coast Salish person in the Salish Sea,” Woodard said.

Samish elder Leslie Eastwood says the loss of kelp around the San Juan Islands, part of the tribe’s traditional territory, has been shocking. To her, it means that the Samish people can’t just rely on Ko-Kwal-Alwoot – kelp – to protect them.

“We as Samish people have also a responsibility to protect her,” Eastwood said. “It's on us to do what we can to make sure that she can survive.”

The tribe is monitoring the health of kelp beds with aerial photographs and a remote-controlled submarine. Samish divers are also training to join the citizen scientists who give Ko-Kwal-Alwoot regular checkups from beneath the waves.