Race is not a health risk factor. Racism is

When it comes to life expectancy, white Americans overall can expect to live longer than Black Americans. That’s not because of biology, but because of the stressors placed on Black people.

Dr. Roberto Montenegro, a psychiatrist with Seattle Children's Hospital, explains.

"Looking at health outcomes by race can be very problematic.

We continue to see ongoing disparities in equity in health and health outcomes. For example, we see that our Black community members continue to have disproportionately negative health outcomes, like increased hypertension, increased complications in surgeries, decreased amount of proper pain management compared to their white counterparts.

When people look at health inequities, and they focus on differences by race, and they argue that race is a risk factor, it clouds the numerous factors that are really behind what people are intending to capture with race.

For example, if they say that African American or Black communities experienced disproportionate preterm births, and they leave it at that, and fail to address the numerous societal and structural systems that are playing a role in preterm births, it connects race as one of the main drivers, health inequity. What the researchers fail to do is look at how the system is failing this particular population and being able to be healthier.

By using race alone without explaining what really is driving these health inequities, we can inadvertently perpetuate that there are biological differences between individuals.

Sponsored

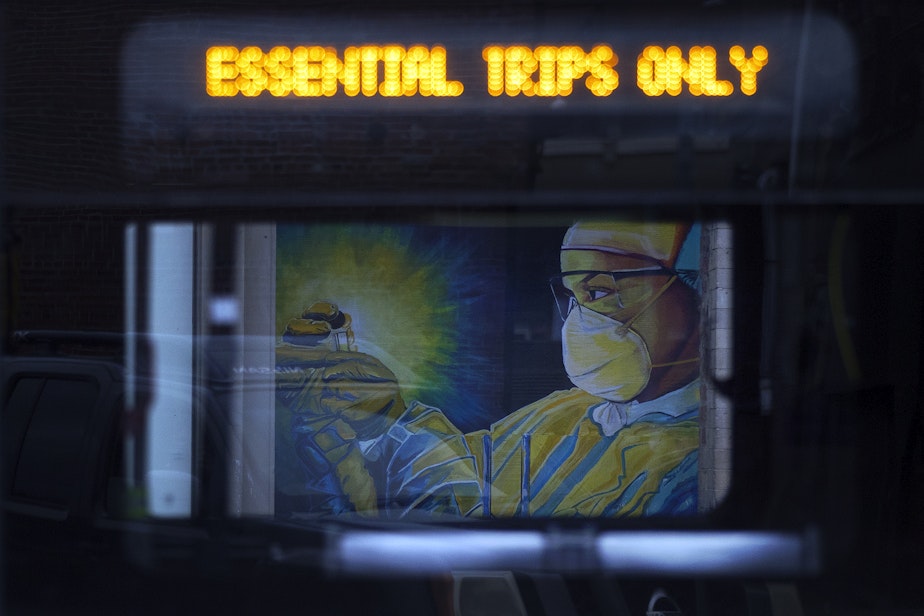

One of the most commonly ignored factors affecting health and health outcomes is racism.

Other factors include access to care, poverty and systemic systems that continue to make it difficult for people to move out of poverty.

Environmental factors also play a big role. Housing segregation plays a big role. Access or lack of access to clean air or an environment that allows individuals to exercise for example plays a role in our educational system and the lack of funding for educational system plays a role in poor health.

For the most part, the health industry continues to look at race as if there are differences between people because of their race. They fail to acknowledge the increasing number of overwhelming research, especially genetic research, that shows that biologically, people are actually a lot more similar than different.

So unfortunately, a lot of our medical institutions continue to use race as a risk factor, which is pretty harming for the research and for the population in general.

Sponsored

It's still a very big, uphill battle. The number of Black physicians is astronomically low; the number of Black physicians in academic medicine is even lower. And representation really matters.

There's also evidence suggesting that providers of color who provide treatment to patients of color tend to have some more positive outcomes and certain outcomes that have been measured.

I think that once we start changing how the institution of medicine works, and who is represented in leadership positions within medicine, and once we start having better representation of positions of color, and specifically, Black physicians in positions of power, change will be slow."

The transcript of this interview was edited for length and clarity.

This story is part of a weeklong series on systemic racism in our institutions. Here are the interviews:

Race and the justice system: 3 areas to target, according to this Seattle professor

Race matters: Understanding how the Central Area was gentrified

Race is not a health risk factor. Racism is