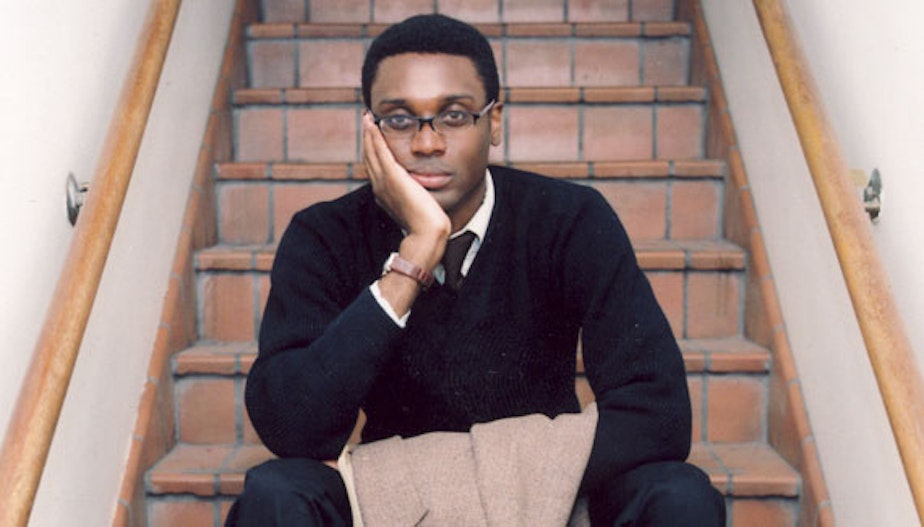

Professional millennial Shaun Scott: We're not that different from you

Filmmaker, author and professional millennial Shaun Scott has a bone to pick about participation trophies. They're just one of many broad brushes with which millennials are painted. But, Scott reminds us, millennials weren't the ones giving out the trophies. The parents were.

In his new book, "Millennials and the Moments That Made Us," Scott explores the contradictions of a generation.

Millennials are the most racially diverse generation in American history, but they're also the most economically disprivileged. And Scott says that the coddling for which helicopter parents are famous masked underlying structural problems.

Having finally left the nest, millennials quickly found that the social safety net enjoyed by previous generations was gone. The book tells the story of how we got there — and how we can get ourselves out.

These are interview highlights from Scott's conversation with KUOW's Bill Radke. Questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Sponsored

You had three generations in your house growing up. How did your parents treat you differently?

I think it's kind of a thing where a lot of baby boomers felt like maybe they had been a little bit too permissive with generation X. Maybe the schools had gotten too lax. Maybe generation X was just sort of written off as a lost generation. I think there's also a sense, in a familial way, that you get a second chance with millennials.

You get the chance to return. To go back to basics.

I should say the gen-X-ers were my generation ... I remember we were the latchkey kids, right?

And we were too. I mean that's something that I think millennials and generation X have in common. I think the difference is that the latchkey entertainment ... you had this whole culture of fear that I remember pretty vividly with D.A.R.E – To Keep Kids Off Drugs, and McGruff the Crime Dog ...

Sponsored

I mean, "Beavis and Butthead" was great. I remember watching that show a lot, and my parents — who were Jamaican immigrants — mostly just thought it was nonsense. So they were like, if you're gonna look at that, we're not going to take you seriously right now. But most parents didn't really have that attitude.

I told this story in the fifth chapter of my book about how there was a kid, I think it was in Florida, who burned down his trailer because Beavis is always saying, "Fire! Fire!" And so one point in time, this kid gets the inspiration to burn down his house, literally. It actually forces MTV to take down the 7 p.m. airing of "Beavis and Butthead" because they figured out that's when the most unattended kids were watching the show.

That's just one of many examples that I try to highlight in my book about how rather than actually giving families and people the resources that they needed to spend more time at home, rather than pursuing paternal and maternal leave, rather than having universal health care, rather than having all these social programs that would make it so that people could spend more time with their kids and not worry about lapsing into poverty or sliding even deeper into it in the '90s, we had this culture-war spectacle where we were paying more attention to ... than we were to the social safety net.

Why did parents seem to focus more on the symptoms – the low hanging fruit – than actual systemic change?

I think it's definitely the case that we culturally have taken a turn. I think at a certain point in time, we made a million different cultural transactions that just put us more in a place where if somebody is struggling or they need help, we're looking at that more as a mark of personal deficiency than as a collective problem.

Sponsored

I think as we made the transition into the 1980s. And that's where you start to see much more of a sense of, if you're having an issue, it must be something that's wrong with you. And that's how I think a lot of young people tend to look at and think about social problems. But I also think as we've aged, we've made a transition out of that. So many millennials were excited by Barack’s campaign, by Bernie Sanders’ campaign. It's the sense that we can actually do something to muster collective will to address social problems.

Would you say that America needs a 1960's-style reckoning where we grapple with income inequality and systemic racism?

There are people who are in the Ku Klux Klan who will get defensive when you call them a racist and say, "I'm not a racist." They're like skinheads who have swastikas tattooed on their bodies who say, "I'm not a racist," right? At one point in time we had a collective referendum on race relations in this country to such an extent that people who are on such an obvious side of the racial divide don't want to be called out for intensifying that divide.

We need to get to the stage where we recognize wealth inequality as a problem ... that's when maybe they'll start being able to recognize class is more of an issue. I think that's kind of the stage that we're at now, where we need to have that kind of a frank conversation about wealth inequality being a big problem.

What would you say to a baby boomer or a gen-Xer who's out of work in some Rust Belt town who says, "I wish I were a millennial – I wish I were a digital native who has a better shot at the jobs of the future?"

Sponsored

That's ultimately what I try to do in my book. In a lot of conversations we have about millennials, we use generational politics as a proxy for talking about a lot of these larger questions ... There are many baby boomers that are struggling seniors who might be vulnerable homeowners, who maybe got bamboozled during the Great Recession with their predatory loan. Many baby boomers who might not be naturalized citizens as it turns out. So these conversations about disapproval use generational politics as kind of a poison pill.

Hopefully, when people read the book or when they listen to this show, they don't think that I'm out here trying to say that all millennials have a halo on their heads. And that if you're a baby boomer, the best that you can do is just fork over the debit card.