'Yogurt for bats': A new way to fight a deadly pandemic

A deadly disease spreads across the country. Millions die as scientists race to develop vaccines and medicines that can lower the death toll. Covid-19? No, this disease is called white-nose syndrome, and its victims are bats.

The bat-slaying fungus has gotten a foothold, or winghold, in Washington state, but scientists are racing to outflank this fungal disease before it decimates bats in the Northwest as it has back East.

A

headlamp lights up the night in front of Leah Rensel’s face.

She’s climbing a ladder in the dark while dressed like she’s about to handle hazardous waste or maybe put on a space helmet.

Sponsored

“I'm wearing what looks rather like a moon suit,” Rensel says.

The Wildlife Conservation Society biologist is wearing a disposable plastic jumpsuit and layers of skintight gloves.

“Everything that comes into this area must be either thrown away or decontaminated using specific chemicals,” she explains.

Tall rubber boots—easy to spray down with disinfectant—cover her feet, while her face is hidden behind an N95 mask.

“We are working with an invasive and deadly fungal disease,” Rensel says. “We don't know if it's here, but we don't want to assist in its spread.”

Sponsored

The disease is known as white-nose syndrome and the fungus behind it is “Pd,” short for the unpronounceable but menacing Pseudogymnoascus destructans.

While there’s no evidence that the fungus poses a threat to any species besides bats, federal researchers say there’s a risk that humans could spread Covid-19 as well as white-nose syndrome to bats.

Rensel is outside the visitor center at Northwest Trek Wildlife Park, a 700-acre city park midway between Olympia and Mount Rainier.

Just below the visitor center’s roof, a colony of about 300 bats, most of them pregnant females, have found a sheltered spot to roost.

Sponsored

“They're starting to get pretty pregnant,” Rensel says. “Looks like they have tiny little golf balls for stomachs.”

Rensel has put up a homemade trap to catch the bats as they head out for the night to hunt insects. Even an expectant mom lugging a fetus one-third her body weight has to zigzag through the night air to chase down food for herself and her young.

Rensel calls her trap “the Rensel graduate school special, built with $80 worth of PVC pipe and shower curtain and fishing line.”

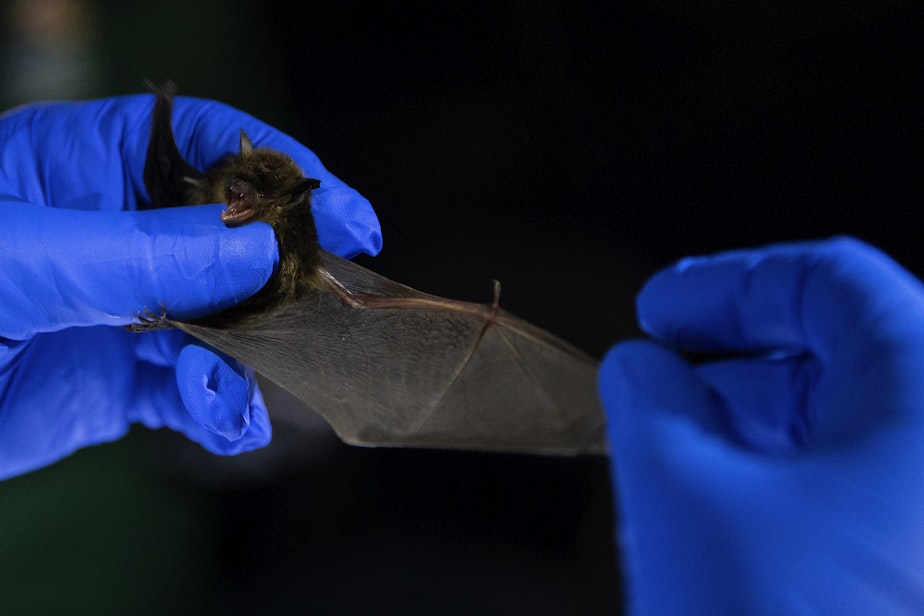

As each bat gets snagged in the fishing line, Rensel climbs the ladder, delicately untangles the bat, and stuffs it into a little cloth bag.

“Hi there, sweetie,” she says softly to one tiny creature of the night as she cups it in her hand.

Sponsored

It weighs about 5 grams, or as much as a nickel.

It squeaks in protest and bites Rensel’s finger.

“Thank you!” Rensel says to the bat.

Later, she explains that the bite of a bat this small doesn’t break the skin, but it does hurt.

“My gut reaction is to yank my hand back and exclaim, ‘Ow!’” Rensel says.

Sponsored

That reaction could break the bat’s tiny teeth or injure it in other ways. So, Rensel trained herself to hold still by saying thank you instead. She says she’s acknowledging the animal’s distress rather than her own minor discomfort.

“I'm also thanking her for reminding me she is a wild animal, who is scared, and deserves care and respect,” Rensel says.

Once the scared little mama is back at ground level, she will get to make her contribution to science and maybe the survival of her species.

R

esearchers and volunteers in protective gear and headlamps are gathered around a folding table that serves as a field laboratory, just around the corner from Rensel’s bat trap.

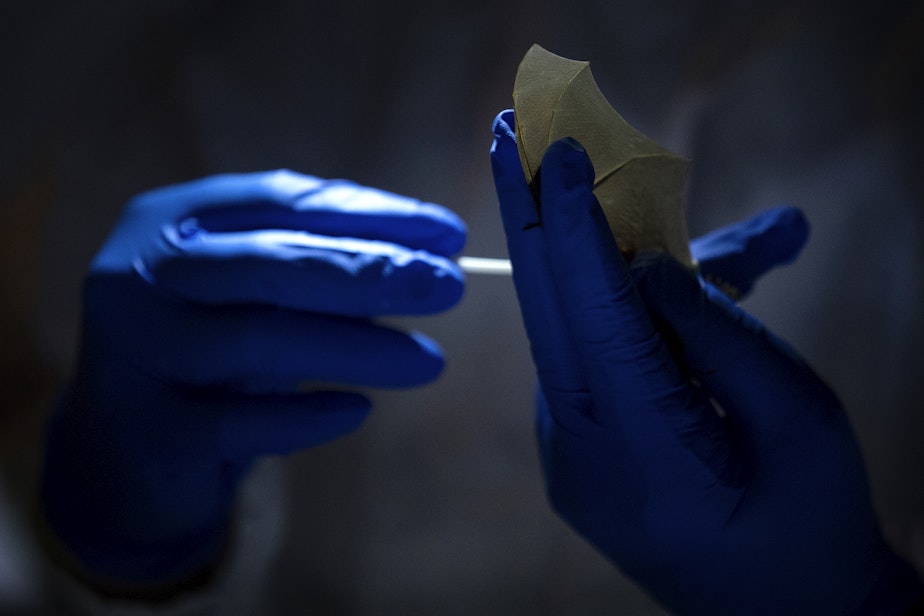

They examine and measure each bat and wipe it with a swab to find out what kind of bacteria and fungi live on its skin. Then the bats that aren’t too close to giving birth get an electronic tag injected under the loose skin between their shoulder blades, so scientists can track them later.

“Like putting a microchip in your cat or dog,” Rensel says.

“Henceforth, this bat will be known as 8299,” she says after implanting its tag.

The researchers want to know if spraying bat roosts with a sort of probiotic supplement can help 8299 and her kind fend off the fungus that causes the deadly white-nose syndrome.

“We call it yogurt for bats,” Rensel says. “You introduce good bacteria into our gut when we eat yogurt—it helps our immune system. We want to do the same for bats.”

This “yogurt” isn’t blueberry- or vanilla-flavored. It’s a freeze-dried mix of four species of Northwest soil bacteria that scientists in British Columbia found suppresses the fungus.

And instead of spoon-feeding it to the bats, the researchers aim to get it onto their fur.

Like little cats with wings, bats groom themselves frequently. They wind up ingesting whatever they may have brushed up against recently.

Unfortunately, perhaps, for 8299, she won't get to benefit from the yogurt treatment. The Northwest Trek bat colony is one of the study's "control" sites, necessary for scientists to compare what happens to bats that get the treatment and those that don't.

Researchers at three Canadian universities and Wildlife Conservation Society Canada have tested the probiotic on bat colonies in the greater Vancouver area. But since white-nose syndrome hasn’t been detected in western Canada yet, the research effort has moved to the fungal hot zones south of the border.

The disease has been spotted in at least five Washington counties since first showing up in North Bend, just east of Seattle, in 2016. The westward-spreading disease somehow leapt some 1,400 miles from its closest known outbreaks in Missouri and Ontario.

Known occurrences of white-nose syndrome in 2016 (above) and 2022 (slide 2).

I

t’s unknown how this European fungus got to America in the first place to unleash one of the worst wildlife die-offs of modern times. Or how it jumped over the High Plains and Rocky Mountains to land in King County.

“It just was introduced, likely from a person, because unfortunately, we can carry the fungus on our clothing or boots,” says biologist Abby Tobin with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife during a break from measuring and tagging bats. “And that's why we're taking these precautions tonight.”

Pd attacks the skin and noses of bats and kills them while they hibernate. It disturbs the bats enough that they wake frequently, burning energy reserves they need to survive until spring without eating.

“It's pretty brutal,” Rensel says. “The bats that are affected often have wing scarring, from where the fungus has grown on their wings, or they're emaciated or dehydrated or in really rough shape.”

“We need to do something for these bats,” Tobin says. “We need to give them a fighting chance against this disease because it’s so devastating.”

I

n eastern states, biologists have been able to treat some hibernating bats with antifungal substances in the caves where they hibernate. But in addition to the logistical challenges of treating more than a few wild animals this way, there’s a virtually insurmountable obstacle to doing the same in the Northwest.

“We don't actually know where our bats hibernate in Washington,” Rensel says. “It's a grand mystery.”

Washington’s bats don’t lend themselves to scientific study easily. They fly fast and at night, often through thick forests or over mountainous terrain, and are almost always silent.

Even identifying a bat in hand can be impossible without sophisticated audio equipment. The two bat species in the Northwest Trek colony, the little brown bat and the Yuma myotis, are nearly indistinguishable without the aid of specialized electronics that can “hear” the bats’ echolocation calls beyond the range of human hearing.

Finding any wild animal, let alone treating it for disease, is no small task. Biologists are often helpless to do much about disease outbreaks in the wild.

Leah Rensel says that’s not the case with bats and white-nose syndrome.

“The beauty of our approach is that you don't have to catch them,” Rensel says. “You don't have to disturb them. You just have to walk up one night while everybody's out foraging for bugs and spray their roost.”

She expects the bats will even help spread the good bacteria as they rub against their neighbors in their colonies.

That fur-on-fur contact can spread the benefits of the bat yogurt much farther than humans ever could.

In bats at least, a disinterest in social distancing can help fight disease as well as spread it.

Federal scientists based in Wisconsin, where the white-nose syndrome has devastated bat populations, have developed a sprayable vaccine against the fungus as well.

They’ve been testing it this summer at maternity roosts in Ellensburg and Washougal, Washington, with a more labor-intensive method: dripping a few drops into bats' mouths.

“We want to ensure they get a full dose,” says Tonie Rocke, a research scientist at the National Wildlife Health Center, a branch of the U.S. Geological Survey in Madison, Wisconsin.

Rocke says the bat vaccine is based on the same technology as the Johnson and Johnson and AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccines for humans. They also share a main goal: to make an often-deadly disease less severe.

White-nose syndrome has taken a terrible toll in the eastern United States, slaughtering 90% of some bat populations. But some bats appear to be turning a corner.

“Bats are developing some resistance to this disease, but it takes time, and the smaller populations can go extinct before that happens,” Rocke says.

She says she views probiotics and vaccines as stopgap measures to keep bat populations or species from going extinct until they can evolve their own resistance to the fungus, as bats in Europe have done after long exposure to it.

Bat researchers still emphasize prevention over treatment, since any recovery from the massive die-off is expected to be very slow.

“Because most bat species only produce one to two pups per year, it can take decades or longer for their populations to recover,” according to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

W

hy go to all this effort to study a fungus few humans will ever see and a mammal that many humans fear?

“Oh my gosh, bats are some of the most amazing species we have,” Tonie Rocke says. “And they're so critical to our ecosystems. There'd be a whole lot more mosquitoes if we didn't have bats.”

Some who work with bats emphasize utilitarian reasons for keeping them around.

“Conserving bats is important to the state’s economy,” according to the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. “Bats are voracious predators of insects, including many crop and forest pests, which makes them valuable to Idaho’s agricultural industry.”

For Leah Rensel, it’s a labor of love.

“I admit I fell in love with bats the first time I saw a tiny pregnant little brown bat yelling her head off,” she says. “I just thought it was the cutest thing ever.”

She loves the bats’ furless, blind pups and the adults’ unusual reproductive cycle: They swarm and mate indiscriminately in the summer, then the mothers give birth nearly simultaneously and raise their young together.

Soon after starting to work with bats, Rensel learned the catastrophic white-nose disease had just been discovered in Washington state.

“It lit a fire under me,” she says.

B

ack at Northwest Trek Wildlife Park, small cloth bags are clipped to a suspended line like socks on a clothesline. Each bag holds a bat awaiting its moment of scientific inquiry.

The headlamped researchers work intently late into the night to examine the bats quickly. They want to minimize the stress the pregnant bats endure and let them get back to eating insects as soon as possible.

“It's tough to raise a pup that's a third of your body weight!” Rensel says.

Only when the bats are released, one at a time, and they echolocate their way into the night, are the researchers able to identify the species they have been closely examining. A bat-detecting audio device identifies the bat colony as a mix of lower-pitched little browns and higher-pitched Yumas.

Later, they discover that three of the 25 bats they tested that night already had white-nose syndrome.

The researchers hoped to start spraying their bat yogurt into roosts at three locations in Washington this summer. But the microbial concoction cooked up in British Columbia was such a novelty that the research team couldn’t get the required federal permit in time to bring it across the border before the bats dispersed from their maternity roosts.

“We are trying to find a lab in the states to produce it so we don’t have to deal with border crossing in the future,” Abby Tobin said by email.

They plan to spray their probiotic into bat roosts, a first for the United States, in the spring.

This story is Part 1 of our series on invasive species in Washington state. We call it: KUOW's League of Murder Creatures.