One hiker's eerie night trekking past a North Cascades wildfire

Mike Campos emerged from days of backpacking across the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest in north-central Washington to learn that a wildfire had blocked off a 40-mile stretch of trail between him and his goal of walking to the Pacific Ocean from Montana.

Campos is what’s known as a “through-hiker”: somebody who hikes the entire length of a long trail.

You might have heard of people walking from Mexico to Canada on the 2,650-mile Pacific Crest Trail.

Mike Campos has done that walk, and the 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail, and, most recently, the 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail from Glacier National Park in Montana to Cape Alava at the tip of the Olympic Peninsula.

“I think I just passed 13,000 miles in the last six years,” Campos said during a trailside interview in September in Olympic National Park, more than 1,000 miles from where he started walking in June.

For the past six years, the nomad raised near Houston, Texas, has worked seasonal jobs near national parks to save up enough to hit a trail again.

Sponsored

“I've gotten really good at quitting jobs,” he said.

“It's just a better life for me,” Campos said of living to through-hike. “It's simple. It's freeing. I don't know what day it is right now. I just slept till 9. Things like that are nice.”

In August, as the Sourdough fire in the North Cascades intermittently shut down the North Cascades Highway and major hydropower dams on the Skagit River, Campos had to decide what to do.

“The trail will still be here next summer. Come back when wildfire and smoke aren’t ruining your experience,” the Pacific Crest Trail Association advises through-hikers. “These are life-threatening events, so take heed and act accordingly.”

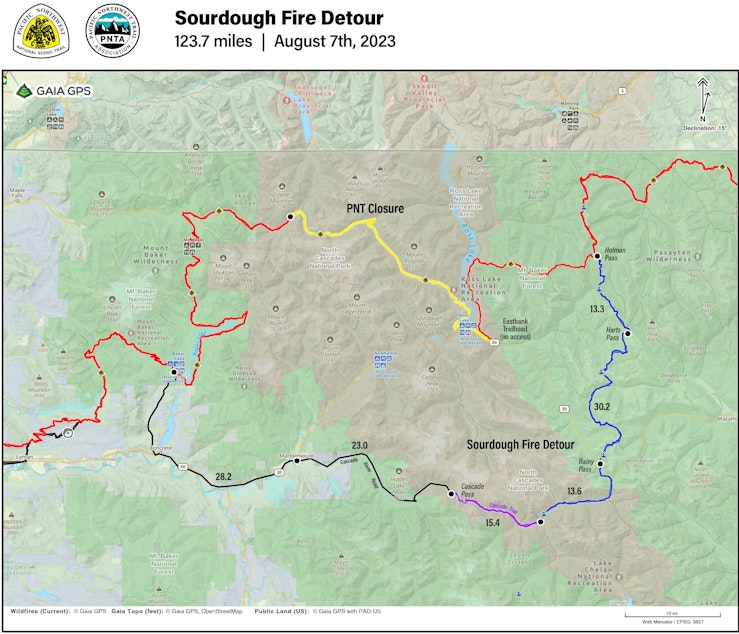

The Pacific Northwest Trail Association was recommending a 124-mile detour to the south, onto the Pacific Crest Trail and rural roads, to skirt the Sourdough fire.

Sponsored

A detour of that length might mean a few hours’ delay for a driver. For a hiker, it’s much worse.

“I'm not a fast hiker,” Campos said. “I usually average about 100 miles a week.”

To make it to the Pacific on his own two feet and shave about 80 miles off the big detour, Campos decided to walk past the Sourdough fire on a road that might be closed by the time he reached it in a day or two.

“I heard the highway was closed. But if a trail, in my opinion, is open to a closed highway, I’m assuming they're leaving it open for people to get their cars out or maybe to walk out,” he said. “There's definitely a gray area.”

Sponsored

Campos decided he would walk an 18-mile stretch of state Route 20, the North Cascades Highway, at night to make it in and out of the fire-closure area quickly.

“I just decided it was going to be about a 45-mile day, and I was just going to hike all night,” he said. “That way, there’s no firefighter activity I would be getting in the way of.”

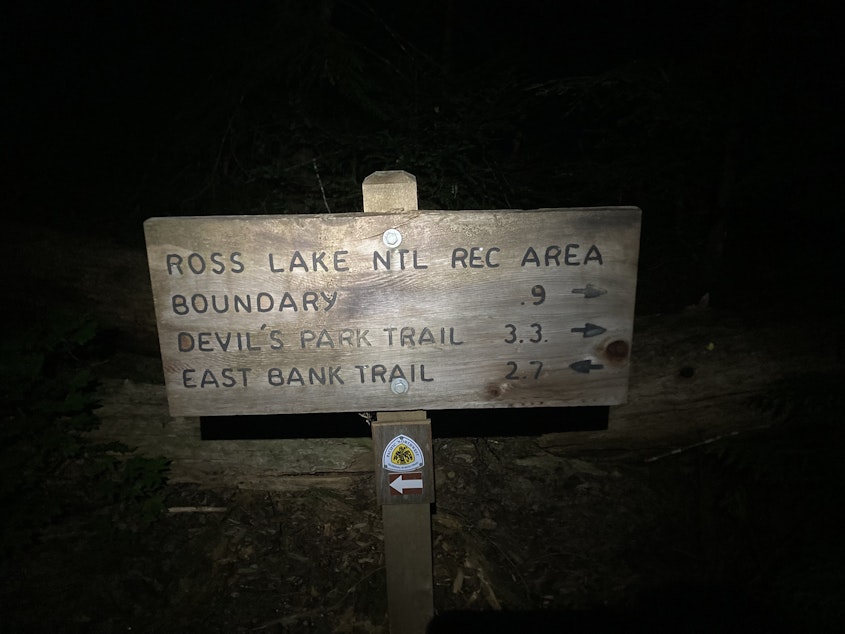

Campos finished the last open section of the trail before the Sourdough fire and walked onto Route 20 about 11 p.m. on Aug. 11.

Sponsored

“The big news of course is that Highway 20 is closed,” Northwest Interagency Incident Management Team section chief Dean Lange said at a Sourdough fire briefing that morning. “It’s closed because we have a lot of rolling debris. Between the rocks and the trees and the fire, it’s the right thing to do to close that road down.”

All through a long night on foot, Campos recorded little hourly check-in videos on his phone.

“Eleven-thirty check-in. I took a little break, filtered some water,” he narrated into his phone without breaking stride. “I’m tired. 27 miles in, I believe. I guess we’re going to do this. We’ll see. This could be crazy, but here we go.”

Around midnight, a park ranger on patrol drove past, telling him the highway was still closed.

“Ranger just pulled up to talk to me. He was just kind of checking on me, letting me know the fire’s pretty close to the highway up here. He said they’ve shut 20 and opened it and shut it a couple times just because the fire has been moving around,” Campos said in his walk-and-talk video just after midnight. “He said he’s not going to kick me off of here. Just wanted to let me know that it’s probably not super-safe. Told me to stay on this side of the highway. Really cool dude for not making me stop walking.”

Sponsored

Campos said a burst of adrenaline from his interaction with the ranger put a spring in his step for the next hour or more.

As he backpacked on the shoulder of Highway 20, mostly without using his headlamp, the night was black as the asphalt, except for scattered points of fire on the mountains above the road.

“You probably can’t see that, but the mountain is definitely on fire, holy shit,” Campos said in a wee-hour check-in video. “All the way up and down, probably 4,000 foot, just a line of fire. Kind of looks like coals right now. But yeah, that whole mountainside is on fire right now. Wild.”

Firefighters by this point had cleared fire breaks and set up hoses and sprinklers around valuable infrastructure near Route 20 — Seattle City Light hydropower facilities, Ross Lake Resort, and the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center. But the fire was considered only 5% contained.

“I’m definitely staying on this side of the freeway,” Campos said.

By about 3 in the morning, he was exhausted but still had about 5 miles to go to get out of the fire zone.

“I’ve never walked by anything like that before,” Campos said at 3:30 a.m. “The fire was right next to the road. Little fireballs rolling down, landing in the ditch right next to the road. Bowling-ball-size rocks, laying in the road. Pretty intense.”

After 18 miles of walking a deserted highway in the dark, Campos made it out of the closure area about 5:30 a.m. Two men stationed at a gate across state Route 20 opened it for him.

“One of them asked me if my friends had left me up in the mountains,” Campos said later. “I told them, 'No, I just walked from Montana.'”

Campos threw his sleeping bag down next to dozens of firefighters cowboy-camping without tents under the night sky before their next shift.

After sleeping in and pounding down a breakfast burrito, sandwich, Gatorade, and beer from a convenience store in the Seattle City Light company town of Newhalem, Campos resumed his walk down Highway 20 to rejoin the Pacific Northwest Trail near Mount Baker.

The Sourdough fire caused his biggest detour, but it wasn’t the only wildfire that interfered with his hike.

“It's kind of just part of through-hiking in the Northwest nowadays, unfortunately,” he said.

Campos had less luck with fires in Olympic National Park in September.

He said National Park Service firefighters wouldn’t let him hike past a fire on Obstruction Point Road inside the park. He was obliged to accept a two-mile ride from them, keeping him from the through-hiker’s goal of making a continuous footpath from trail’s start to finish.

About 70 people hike the entire Pacific Northwest Trail each year, according to Eric Wollborg with the Pacific Northwest Trail Association. In 2022, 868 people through-hiked the much better-known Pacific Crest Trail between Mexico and Canada, according to the Pacific Crest Trail Association.

Those hardcore accomplishments are getting even harder as the climate changes, according to some trail officials.

“There's a good possibility that the days of hiking the PCT from beginning to end are over, and it may very likely be impossible in the not too distant future to be able to do that,” Scott Wilkinson with the Pacific Crest Trail Association told the Palm Springs Desert Sun. “It's been almost impossible the last few years, due to wildfires and other extreme weather events.”

On Sept. 13, Campos reached Washington's Cape Alava and the end of the Pacific Northwest Trail at the westernmost point of the contiguous United States. He then road-walked another 50 miles to meet up with his mom in Forks.

He said he’s already thinking about where to do his next big hike.