Nine crucial days: Without local medical staff help, Life Care had to wait on a federal strike team

The 63-year-old man turned blue and struggled to breathe, the Life Care Center worker told an emergency dispatcher by phone on March 1.

The man hadn’t traveled out of the country, to Asia, Iran, or Italy in the last two weeks, the worker said. But she noted that days earlier two people -- an employee and a resident -- at the Kirkland assisted living facility had been diagnosed with coronavirus.

Staff would also succumb to the virus, and at one point, the Life Care Center had lost a third of its staff to the virus, with the remaining caregivers working 18-hour shifts. Of 180 employees, 55 have now tested positive for coronavirus. But even as international focus zeroed in on the nursing home, Life Care wasn’t getting outside help, said spokesperson Tim Killian.

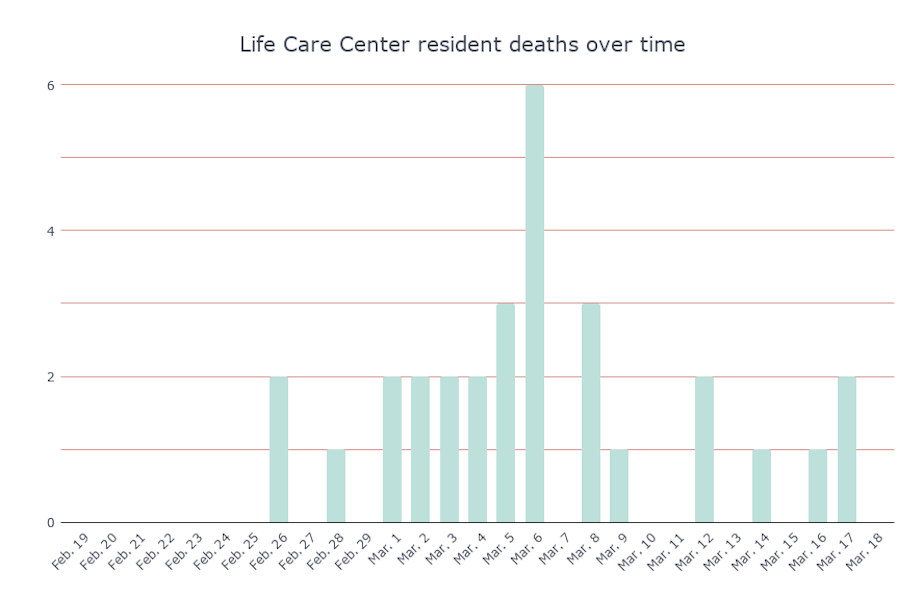

It took nine days, from the moment the outbreak became known, for an outside medical team to come to Life Care -- a strike team from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. During that time, 18 residents from Life Care died.

Instead, Killian said, during those nine days they were swamped with paperwork from government agencies “asking us to spend administrative time searching down email lists and filling out documents and paperwork,” he said. “We were just doing everything we could to provide care to the patients that needed it.”

Jeffrey Duchin, the health officer for Public Health, Seattle & King County, said he asked hospitals to offer staff, but he didn’t get that help.

“I personally would have thought that we would have been able to muster more staff from our local healthcare system,” Duchin said. “But I think everybody at this point was already experiencing some degree of COVID-19 stress, and didn't feel like they had staff that they could spare.”

“I would have thought we would have had a more robust reserve,” he said.

As of this writing, 35 people connected with Life Care have died -- that’s 12 percent of all residents and staff.

Those deaths make up roughly half the coronavirus death toll in Washington state.

Day 0: Before the outbreak became known

On February 27, Seattle & King County Public Health’s communicable disease program received what they believed was a usual winter time message from Life Care.

The nursing home had several residents who had fallen ill with a respiratory bug. Public Health had received 19 notifications of flu outbreaks at other facilities. Life Care’s situation did not immediately cause alarm.

That same day, officials from the EvergreenHealth hospital in Kirkland notified Public Health that they had two patients with unexplained pneumonia, one of whom had been a resident at Life Care. A second nearby hospital reported a similar case, instead it was an employee.

The patients were unlikely to have coronavirus, public health said. There wasn’t yet evidence that the virus had spread between people living in the area -- what is known as community transmission. But the CDC had changed testing criteria, and patients with unexplained severe respiratory disease or pneumonia now qualified.

DAY 1: Outbreak becomes known

The next day, on Friday, February 28, public health learned that 20 residents and 18 staff members at Life Care were ill, and that their flu tests had returned negative.

Life Care implemented verbal warnings about the outbreak and provided additional protective gear for visitors to wear, due to the sheer amount of illness at the center. In the days that followed, policy went from discouraged visitation to eventually no visitation at the facility, Killian said.

Public Health guided Life Care to use the common protocols used to contain the spread of the flu: create cohorts and limit movement within the facility.

And then, that Friday evening, two batches of results showed that four people in the Seattle area had tested positive for coronavirus, two of whom were connected to Life Care. It was at this point that Public Health leaders reached out to the Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Soon after, EvergreenHealth community hospital in Kirkland informed county public health that one of their patients with coronavirus had died. It would be the first coronavirus death in the U.S.

DAY 2: CDC team deployed

The CDC deployed a team of 18 to King County the next day, and in the next six days, the CDC and Department of Health carried out walk-through evaluations, gauged training and supply needs, and examined response activities.

The CDC conducted infection prevention training, gathered information on staff absences, reviewed clinical data from resident records, and continued their evaluation of the circumstances. They conducted personal protective equipment training and discussed communication challenges.

DAYS 3 & 4: Administrative help doesn’t cut it, Life Care says

For Life Care, however, the administrative tasks were not enough. To those inside, it felt like the nursing home was managing the outbreak alone as public health officials took notes on the sidelines.

"We have largely been left on our own to figure out how to manage this," Killian said.

It wasn’t until a week later, a U.S. Health and Human Services strike team of 28 doctors, physician assistants, nurses and technicians would arrive, and testing would be completed for all residents at Life Care.

Duchin said he assumed federal assets would have been on the ground and in Kirkland much sooner. “It did take a while for that. I don't really understand why at this point,” Duchin said.

When asked how the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services felt about their response to Life Care, a spokesperson wrote “At the request of [Washington] state, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services deployed a team of public health and medical professionals to augment the clinical staff at Life Care.”

The Washington State Department of Health said the strike team request came from Public Health, Seattle & King County. The spokesperson later added that two DOH nurses worked three night shifts to cover staff shortages, but did not immediately provide dates.

A county Public Health spokesperson said the request for the strike team had been put in several days before the team was deployed on March 5. However, the spokesperson did not have the details available on who sent the request, or when the request was made. “I’d suggest reaching out to DOH or HHS for more information,” they said.

On the county’s response to the Life Care Center, Patty Hayes, director of Public Health, said “I’ve reflected on the first two days of the event and we responded immediately, which is what all of our preparedness exercises would have had us do.”

The CDC declined to comment on its response.

Lori Spencer checked her mother into Life Care on February 26, after a surgery at Swedish Hospital. Spencer chose Life Care because it was recommended as a five-star facility. She checked her mother in on a Wednesday afternoon and by Saturday, got the call that two people inside the center had coronavirus.

“[My mother had] been watching the ambulances leaving and hearing people cough in the facility,” Spencer said, adding that she was surprised the CDC didn’t just “come in and take the center over.”

“The Life Care Center has continued to cripple forward and do business as usual with the added help coming in. I was hoping to see immediate change,” Spencer said.

Curtis Luterman’s mother was another resident at Life Care. Luterman said after he learned of the confirmed cases within the facility, there was miscommunication all around. But he did not hold Life Care fully responsible at the time. He said Public Health officials were overwhelmed, unresponsive and gave out false information which caused families distress.The CDC response and assistance was worse.

“In attempts to get help, various agencies would suggest you contact the other,” Luterman said. “Then upon finally reaching the other, they would refer you back to where you started … It seems it took nearly a week for the correct channels to be developed.”

Charlie Campbell's dad was admitted to Life Care on Feb. 21 and transferred out to Swedish on March 6. During his father’s stay at Life Care, he noticed discrepancies between what news agencies were reporting and what he saw happening.

“I kept hearing everyday that we were at the Life Care Center or outside the media would say ‘Test kits are on their way today. Everybody is going to be tested today’ and then [residents] didn’t get tested. The next day the same thing happened,” Campbell said.

He felt frustrated to have his dad wait days for testing and watched as celebrities and those aboard the Grand Princess cruise ship were all tested at a faster rate. Five relatives of Life Care residents that KUOW spoke with called the government’s response “slow.”

DAY 5: A North Carolinian gets coronavirus from Life Care

By March 3, cases connected to the Life Care Center were cropping up across the country. The first person in North Carolina who tested presumptive positive for coronavirus was exposed to it at Life Care. Today, media reports say there are more than 200 cases in North Carolina, including the state’s first community transmission. Other infections were caused by travel or contact with people confirmed to have the virus.

DAYS 6-9: Help trickles in

On March 4, government agencies delivered swabs for testing and trained Life Care staff to do COVID-19 testing for residents, according to Public Health, Seattle & King County. The testing on residents was completed by Sunday, March 8.

Before testing could happen, staff had to get consent from residents to swab them, according to the CDC. For some patients this meant tracking down guardians. Once the samples were collected they were packaged and sent off to the Washington state health lab for testing.

Three days later, on March 7, the federal strike team began onsite support of Life Care.

Today, the situation at the Life Care Center has improved as some staff were allowed to return to work, Killian, the nursing home spokesman, said. However, the center is still “in the trenches” battling the virus.

Killian said he’s not trying to point fingers, and appreciates the outside support Life Care has received. But he hopes that if and when coronavirus erupts elsewhere, it doesn’t take more than a week for staff and residents to be tested and for additional doctors and nurses to arrive.

“Nobody in government seemed to take that they were part of what needed to be a cohesive solution between all of us,” Killian said. He later added “There's a different way we could be doing this work together … I need your help more than I need your inquiry and oversight … If you want to be in touch with families get down here. Put a team on the ground. We welcome the help.”

Duchin said Wednesday that there were 23 assisted living facilities in King County with coronavirus cases among staff or residents. He said the situation that Life Care faced, based on what they observed, was not unique to the facility. “This could happen anywhere.”

Ashley Hiruko can be reached at hiruko@kuow.org and by direct message on twitter @Ashleyhiruko.