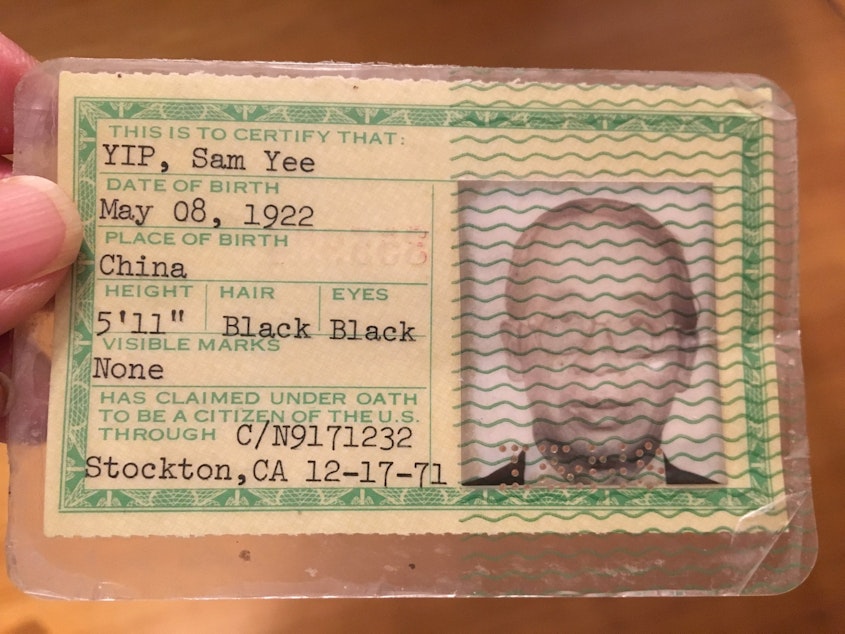

My grandfather was a paper son under the Chinese Exclusion Act. He created an iron legacy.

T

he Chinese Exclusion Act was a discriminatory immigration law that barred Chinese immigrants from entering the United States from 1882 until its repeal in 1943. The Act was the first immigration law to exclude an entire ethnic group.

Under the Chinese Exclusion Act, people had to create false papers to immigrate. My grandfather, who came here in 1937, had to pretend he belonged to another family. It took him decades to build his own family.

My gung-gung — my maternal grandfather — passed away in 2017.

At my gung-gung's funeral, I heard the story of how my grandfather left his mom when he was young and traveled to the United States. As someone who is going to college in a few years and terrified of living on my own, I was intrigued. So I asked my poh-poh — my maternal grandmother — to tell me the story.

She told the story in Toishanese, a dialect of Cantonese, and my mom translated it for me.

My gung-gung was born in a rural area of Southern China in 1924. He was 15 years old when the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out, causing many schools to close. His father sent him to Boston with papers saying he was two years older than he was.

My gung-gung came to America during the Chinese Exclusion Act, which said that Chinese people couldn't immigrate to America unless they were related to an American citizen.

Many Chinese immigrants would forge papers saying they were relatives of American citizens, when in fact, they were just trying to immigrate.

My gung-gung was one of tens of thousands of these "paper sons" who lived with fake families. However, according to my poh-poh, he was supported by his dad, who lived in Canada.

Although they couldn't live together due to stricter Canadian immigration laws, my gung-gung's father provided for him by bootlegging, or illegally selling alcohol during Prohibition.

But he died suddenly just before my gung-gung was about to graduate high school, forcing my grandfather to drop out of school in order to support himself. From then on, my gung-gung found it hard to get a good job.

"Back then," my poh-poh told me, "most people only hired white people or people with high school diplomas."

He often left the jobs he did find because of the prejudice he faced.

"They would use the word 'Chinaman,'" my uncle, my gung-gung's son, told me. "He was very upset when he heard that word."

My uncle was born shortly after my gung-gung went back to China to find a wife and met my poh-poh. When my grandparents decided to get married, they were not motivated by love.

My poh-poh wanted to come to the United States, and because my gung-gung was nearing his 40s, he wanted kids.

They would go on to have three kids together, and while my gung-gung still struggled to find work, at least now he wasn't alone.

My gung-gung worked hard. Eventually, he discovered that he finally had something he'd been missing his whole life: a real family.

"He would ask me to make dim sum and Chinese food all the time," my poh-poh told me. "He didn't grow up having anything."

Food was the thing that brought them together, so my gung-gung decided to use food to bring more people together.

"He wanted to own a small restaurant," my poh-poh said, "so he could make enough money to petition to have my family immigrate from Hong Kong. My family would come and help him run the restaurant."

My gung-gung would go on to own several restaurants in his life, allowing him to bring over not just my poh-poh's family but also his distant relatives and family friends in a process called chain immigration.

"He directly had an effect on twenty people, but then those twenty people established roots in the United States and had families of their own," my uncle said.

My gung-gung had few options, yet he managed to make a family.

With all of the opportunities and information I have available to me, I still don't know whether I could do the same. But hearing my gung-gung's story has inspired me to try.

This story was created in KUOW's RadioActive Intro to Journalism Workshop for 15- to 18-year-olds at Jack Straw Cultural Center, with production support from Kamna Shastri. Edited by Joshua McNichols.

Find RadioActive on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and on the RadioActive podcast.