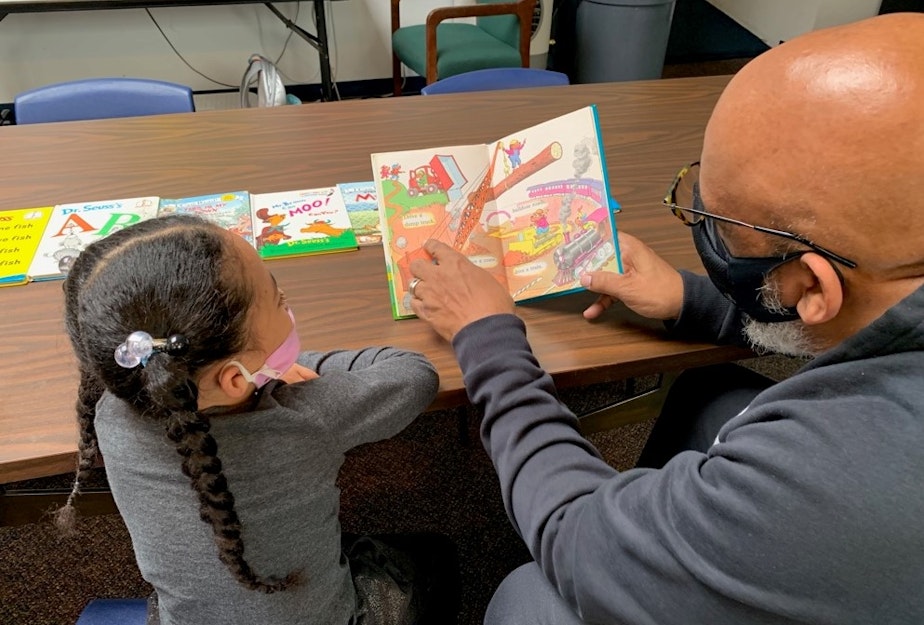

Mr. D and his ‘babies.’ A veteran educator and the toughest year of his career

Before the pandemic, a typical school day for Gerald Donaldson would start around 6:30 a.m., with a trickle of sleepy kids shuffling into his office at Leschi Elementary. Some were homeless students, who arrived in the dark of morning, in taxis provided by the district.

Others came because their parents worked early morning or overnight shifts and had a gap in childcare. Donaldson’s office -- and his grandfatherly style – gave them a refuge.

“They play LEGOs, they tell me stories; I tell them stories,” Donaldson says. “They’d sleep or have breakfast. And then we just had a chance just to talk, you know...just about anything.”

But this school year is nowhere near typical, with students attending school online and Donaldson’s office now closed. He’s facing the biggest challenge in in 30-year career as a family support worker with the Seattle School District, and he sees so much more on the line than grades.

“People who’ve never asked for assistance are asking now,” Donaldson says. “You see families who were doing well, really struggling. You see it in their faces.”

Sponsored

He worries, especially, for the children he no longer sees in person, passing through his office. He used to rely on their visual cues to know when a family is stressed.

“You could be hungry; you didn’t sleep well,” he lists off. “Parents working overtime, there could have been an argument, anything could have happened.”

Donaldson is one of 20 family support workers placed in Seattle public schools with the highest poverty rates and most need.

Leschi Elementary has been his home base for 26 years, long enough to see many former students return, year after year, as parents of incoming kindergarteners. He's known to all of them as, simply, Mr. D.

His job is like a Swiss Army knife. His phone earpiece is always on, and ringing.

Sponsored

He’s partly a case worker for families in crisis or hardship, helping connect them to resources for food, housing or other assistance.

During school, students are often sent to him with discipline “challenges, not problems,” as he calls it. He also runs support groups for Black boys, focused on academics and leadership.

Now he tries to keep this all going through Zoom, phone calls, occasional home visits and meet-ups outside the school building.

Donaldson also spends a few mornings each week at a youth center where a small group of Leschi students meets every day to get online for their classes.

Sponsored

It’s valuable time for him to check-in face to face with these students and parents, almost as a bellwether of how the wider school community is coping.

“Things are okay right now,” one mom told Donaldson on a recent morning, as she dropped off her two daughters at the center. “We live day by day,” she says.

Donaldson reminds her and the other parents who stop in to call or text him if they need help with rental assistance, internet hot spots, counseling, or just someone to listen.

As for the kids, he sees them put up a good appearance in front of their peers, on the screen.

“But then when you get calls from mom, Grandma," it’s a different story, he says. “Zoom is fun for anybody at first; it was for me."

Sponsored

“It sucks,” he says, letting out a big sigh.

He hears the usual complaints – it’s boring, confusing, things don’t work.

But students also confide in Mr. D. about other fears they have with online school. Here’s a big one:

“If I ask my question in Zoom, everybody will hear,” some students have told him. “There's no one-on-one. That's scary. Because if somebody is willing to ask you a question, and you can't get to them, they're going to stop asking. Then pretty soon they'll be disengaged. That's how we lose our babies.”

Our babies. That’s what he calls all the students.

Sponsored

And he knows the pain of losing them, when they fall away from school and into bigger trouble.

“I’ve been to way too many funerals, way too many visits to the hospital,” he says, remembering students who later got involved in violence, or were “in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

That long-term risk weighs on his mind with school connections strained this year. He doesn’t want it to create a downward spiral.

He pushes for more focus on students’ emotional support and metal wellbeing this year – from parents, teachers and the school system as a whole.

“If they’re not secure emotionally and stable financially,” he says, halting. “I don't know if academics are that important. Honestly, I don't.”

He hopes that educators get time to reach out more to individual students and families. He also encourages listening circles as a good way for kids to open up about their worries, to know they’re not alone, and sometimes find solutions together.

He’s started seeing a therapist himself, to help find ways to cope with the stress, for the first time in this 30-year career.

Asked how he’s holding up, he says “up and down,” his voice cracking, as we sit outside the youth center, masks on and six feet apart.

"A little challenged. Excuse me,” he says, taking a minute to wipe his eyes and catch his breath.

"When you can't provide,” he says, “When you know there's a need and you just can't get there. That hurts.”

At 65, he’s wrestled with retirement for years but hangs on for more "babies” he wants to see graduate, or families who need just a little more time to find stability.

But this chapter is not the one he wants to end on.

He tells himself he’ll need at least one more year back in the building with students. He needs to see his "babies” in person, see their faces, and know they are okay.

Editor's Note: The author's son is a student at Leschi Elementary.