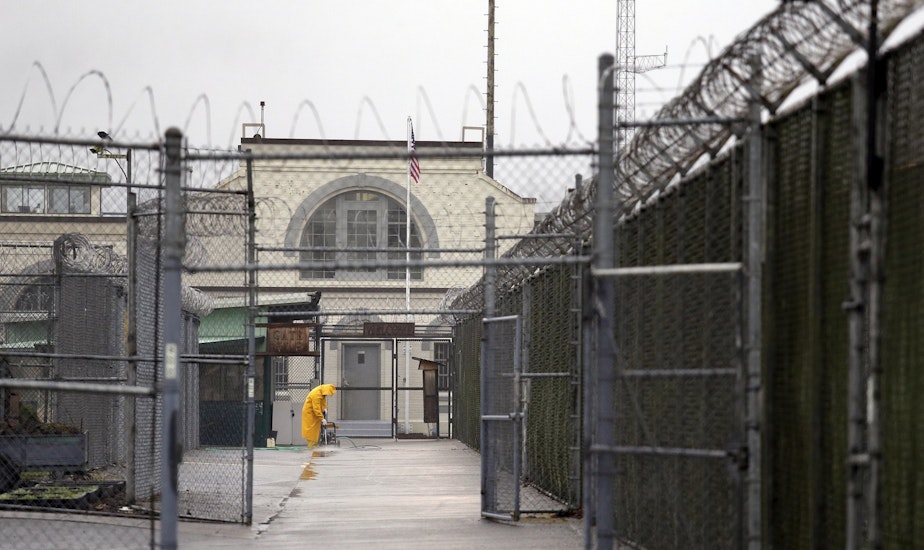

'We're scared.' Inmates at two prisons protest peacefully, call on Gov. Inslee for coronavirus protection

Monroe Correctional Complex inmates were so worried out about getting coronavirus that they rejected bribes of McDonald’s fast food to move into wards they believed had been contaminated with the disease.

On Wednesday, inmates had acted out after their cellmates and prison staff continued to test positive for coronavirus. They called for better distancing practices and more masks and cleaning products.

The next day, Thursday, Gov. Jay Inslee and Stephen Sinclair, secretary of the Washington Department of Corrections, addressed an inmate protest within Monroe Correctional Complex. Sinclair said the inmates hadn't been cooperative.

But those inmates families, and former Monroe inmates, told KUOW why they believe Washington state and Gov. Inslee aren’t doing enough to protect those within the Monroe Correctional Complex, where at least seven inmates and five staff have Covid-19.

Among their concerns: Inmates suspected of having coronavirus being sent to isolation units.

The Department of Corrections reported on April 7 that about 17 incarcerated men were housed in the isolation unit, where a health care team is monitoring for safety.

Sponsored

Jeremiah Bourgeois, a former Monroe inmate, said he wouldn't be surprised if inmates were reluctant to isolate. Bourgeois, now a journalist and prison reform activist, called the move to place symptomatic inmates into isolation problematic, as isolation is typically used as a form of punishment.

Inmates who have symptoms, but are deemed disingenuous by employees, could suffer repercussions, he said.

"When that is the choice, I'm going to stay in my cell and say absolutely nothing and hope that I’m not infected with the virus," he said.

Suzanne Cook, whose husband is a Monroe inmate, echoed that segregating the vulnerable was not enough.

Her husband, who is 62 with underlying health conditions, is currently being kept on the fourth floor of the Monroe Correctional Complex's main building, in a segregation cell. He is being kept their for behavior, not coronavirus.

Sponsored

Cook said her husband has watched as vans of people have brought inmates into the isolation unit, without telling the others there whether they were Covid-19 positive, or from where within the prison the inmates transferred in.

“Without that kind of clear communication to everybody, that’s where rumors start and that’s where people are just lashing out and they’re afraid,” Cook said.

Cook said she worried the coronavirus is spreading between inmates by way of the guards. Her husband told her that guards working multiple shifts go between the different areas, including the vulnerable populations in the medical ward.

She said her husband told her that he feared he’d be stuck in the prison and never get out. "That they’re going to shut the doors and leave these people to fend for themselves,” Cook said.

Bourgeois said that while Inslee may have been forward thinking with regard to Washington state in general, he wasn’t proactive in protecting inmates, Bourgeois said.

Sponsored

The governor has voiced the idea of potentially releasing “non-violent” offenders nearing their release date.

Bourgeois said he would like the governor to consider releasing inmates who have already served years of their sentence.

On Friday morning, Washington state responded to an emergency motion that Columbia Legal Services had filed with the Washington Supreme Court on behalf of incarcerated petitioners.

The lawsuit called for the release of thousands of prisoners.

In the response, the state argued that the release of two-thirds of the state’s prison population would endanger communities across the state, and threaten the health and safety of inmates released without housing, jobs and medical care.

Sponsored

They argued that the Covid-19 response was satisfactory, given they had implemented steps to mitigate Covid-19 risks, including enhanced screening, provided education to inmates on the coronavirus, approved the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, and made sure free soap and hand washing spots were available.

Columbia Legal responded to that response, writing that the Department of Corrections hadn't been following Centers for Disease Control guidance that recommended close contacts of those who test positive for Covid-19 be quarantined individually, instead of in a group setting.

They wrote that quarantined and non-quarantined people continue to be allowed in close contact in the same areas. The legal response quoted Secretary Sinclair speaking at the press conference.

"Rather than take the steps necessary to protect people in DOC’s custody from an imminent Covid-19 outbreak, Secretary Sinclair, the Governor, and DOC are relying on hope," Columbia Legal lawyers wrote.

Others agencies, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, have put their own proposals before the governor. The NAACP's proposition would create additional space within prisons, to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

Sponsored

The proposal called for the release of all prisoners whose crimes were committed before 1984 (geriatric and vulnerable inmates), release of all prisoners from the remote camp facilities throughout the state, and use the camps to house prisoners impacted by COVID-19.

"Camp prisoners have four years or less remaining on their sentences and are getting out anyway. Camp prisoners work out in the community every day, and therefore do not pose a public safety concern because they are already out in the community," wrote Gerald Hankerson, President of the Alaska, Oregon and Washington State Area Conference of the NAACP.

Hankerson estimated these moves would provide the Department of Corrections with 2,000-plus beds for isolating and treating prisoners and staff impacted by coronavirus.

By Friday evening, the court had called on Gov. Inslee and Sinclair to "immediately exercise their authority to take all necessary steps to protect the health and safety of the named petitioners and all Department of Corrections inmates in response to the Covid-19 outbreak."

They have until noon Monday to outline the steps taken and emergency plans they have to protect state prison populations.

Until then, inmates across the state continue to speak out.

Bourgeois said it is noteworthy that the protest was in the minimum security unit in Monroe.

“Everyone there is serving under four years and all of them have the most to lose in respect to getting involved in disciplinary conduct,” he said.

He said it’s a bellwether for what is likely to happen over the coming weeks within prison systems across the country, if the pandemic is not handled effectively by correctional systems.

It didn't take long.

On Thursday evening, another inmate protest took place at the Cedar Creek Correctional Center in Little Rock, Washington.

It ended at 12:30 a.m. after inmates peacefully stood outside and called for safer living conditions for themselves and officers.

Speaking from the prison courtyard to reporters, they said it’s impossible to social distance while inside and too much cross contamination was happening between guards and inmates.

“Please help us,” one prisoner voice rang out, from the other side of a chain link fence.

“Nobody in here signed up for a life sentence,” another followed.

“We’re scared.”