Many children have lost parents to Covid. Here's how they're coping

C

hristy Maricle’s home in Puyallup has two Christmas trees: downstairs, a traditional one and upstairs, a “dad” tree, which Maricle decorated with ornaments that remind her and their three kids of their late father.

“We have some Seahawks ornaments,” she said as she showed off the tree. “He was definitely a Seahawks fan. We have ‘The Office.’ He loves ‘Office’ and ‘Entourage.’ Traeger — loving to grill.”

Kurt Mrsny died in September 2021. He was only 40 years old, and his family had no time to prepare: He got Covid, and a week later, he was gone. He and Maricle had three children: a son who was 19 at the time of Mrsny’s death, and two daughters, who were ages 12 and 5.

“We would watch movies together,” said Caileigh, the youngest. “And sometimes we would grill burgers for dinner.”

Sponsored

Caileigh and her siblings are just three of more than 1,400 kids in Washington state who have lost a caregiver to Covid. They’ve turned to family and friends, their school community, and a center for grieving children to try to patch their lives back together in the wake of their father’s death.

In many ways, the needs of families who’ve lost a caregiver to Covid are similar to the needs of any family that’s lost a parent: grief support, mental health counseling, a way to replace lost income, help with logistics, and childcare.

But the scale of Covid deaths creates a unique set of challenges: there’s no formal government support for families in this situation, which means an increased demand and long waits for programs that help families cope with loss or financial hardship.

Maricle said the first thing she needed after her husband died was to figure out how to talk about it with their kids.

Sponsored

“I was so concerned about ‘What do I tell my kids? How do I tell my kids?’” she said. “All those thoughts just consumed me.”

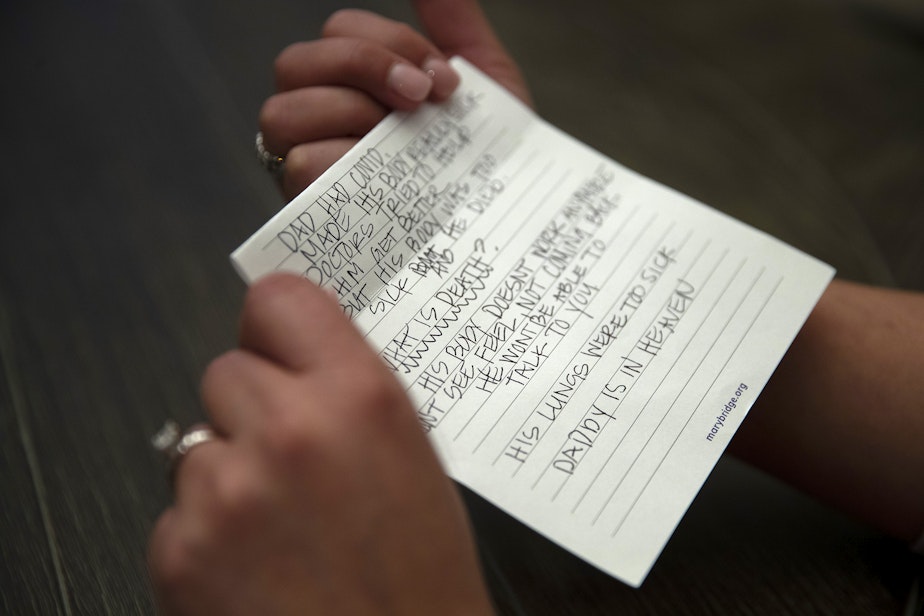

The hospital connected her to a grief counselor, who helped her write a script. When she got home, she gathered her children into her bed and read what she’d written out loud.

“Dad had Covid,” she said. “It made his body really sick. Doctors tried to help him get better. But his body was too sick. He died.”

The grief counselor coached her to make it clear: He’s not coming back.

“Moments later, we were all just hugging each other in my bed,” she said.

Sponsored

Kurt Mrsny had been the sole breadwinner; Maricle had been a stay-at-home mom. So Maricle urgently needed to find a job.

“I was like, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do. I just know I have to get to work,’” Maricle said.

Then, her husband’s boss called her and offered her her husband’s job — even his old office — at an HVAC company. She accepted.

Replacing that lost income was crucial, and most other families wouldn’t have such a straightforward solution.

Sponsored

The job gave her stability and the means to help tend to her family.

Her college-aged son, Cadence, said he felt unmoored by his dad’s death.

“I would always ask him what I should be doing to know what my next move should be,” Cadence said. “Without that, I’m kind of just winging it.”

Cadence was the first in his family to attend a four-year college: the University of Montana, on a lacrosse scholarship. At the time his dad died, Cadence had been taking a year off from school.

Sponsored

“I loved school for the fact of going to be able to play the sport that I loved,” Cadence said. “The sport in general just brings up mixed emotions now, just because I know that was the one thing he loved seeing me do. It makes me not want to do it without him being able to see it.”

Cadence gave up lacrosse, and he never went back to school. Instead, he got a job retrofitting HVAC systems at the same company where his mom works.

Children and adolescents who lose a parent are more likely to drop out of school and have lower earnings throughout adulthood.

To cope emotionally, Cadence has been relying on his childhood friends; he tried group therapy, but it didn’t work for him.

“My friends that I’ve had for a long time had pretty good relationships with my dad,” he said. “All of my friends loved him.”

Cadence’s younger sister Kaitlyn, who’s now 13, needed more structured grief support and mental health counseling.

She said after their dad died, it was really hard for her just to get out of bed, “because you were just like so upset or sad that it was just hard to … get up or do stuff,” she explained. “Going back to school was really hard.”

“On the day we were going to go back to school, she pulled up at the school and just bawled,” Maricle said. “She couldn’t even get out of the car.”

Losing a parent can put kids at risk of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, and can make it difficult for them to attend to day-to-day tasks, like getting dressed and going to school.

The school counselor came up with a plan for Kaitlyn to get back to school, one step at a time. On the first day, Kaitlyn just walked up the steps, gave the counselor a high five, and then went home. The second day, she went into the counselor’s office and said hello.

It took about a month for her to attend a full day of school.

Finding an individual therapist who took their insurance and worked with Kaitlyn’s school schedule took almost a year.

Kaitlyn ultimately got the mental health support she needed at school and through private therapy. But not all schools have enough counselors for all their students, and getting into private therapy can be both difficult and costly.

Kaitlyn also tried group therapy; it didn’t work for her. But studies have shown that children who attend support groups after losing a parent are less likely to suffer trauma from the loss or develop behavior problems, and they have better health and self-esteem.

The youngest Mrsny, Caileigh, has been attending weekly support groups for almost a year at the Bridges Center for Grieving Children, at the Mary Bridge Children’s Hospital in Tacoma. There, she does activities to help her process her feelings and learn the language to talk about them.

At an evening support group at Bridges in late November, about a half-dozen kids between ages 7 and 9 sat around a low table, writing and talking about their parents who had died.

The facilitator asked the kids how they felt when they found out about their loved one’s death.

“Sassy,” one girl volunteered.

The facilitator prodded her to tell more.

“This is unacceptable!” is how she described feeling at the time.

“We have another word for that besides ‘sassy,’” the facilitator told her. “You know what it is? ‘Denial.’ Did anyone ever feel like that, where they didn’t want it to be true?”

“I didn’t want it to be true,” another girl volunteered. “I thought they were just goofing with me. And I said, ‘That is not funny!’”

Christy Maricle said her daughter gained a lot during her time in Bridges.

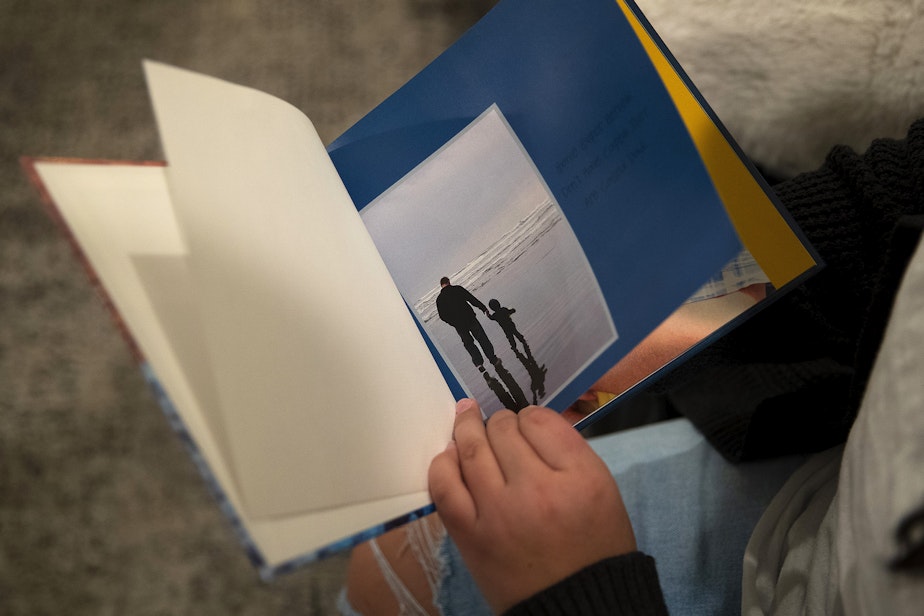

Maricle found out about Bridges right after her husband died, and the program sent her care packages for each of her three children. They included memory boxes to decorate and fill with things that remind them of their dad.

Caileigh keeps hers in her room.

“She has a little dad shrine area,” Maricle said. She and her daughter walked over to it.

“So you have pictures of you and Dad,” Maricle said. “What’s this little sloth guy from? How did you get that?”

“Daddy, from Valentine’s Day,” Caileigh said.

Maricle said another girl in Caileigh’s Bridges group even goes to her school.

“So you’re kind of like, ‘See, you’re not the only one. Maybe you can talk to this person and you can share your feelings, or maybe they’re going through the same thing,’” Maricle said.

There’s a high demand for programs like this.

Lisa Duke is a social worker and the program coordinator at Bridges. She said they never had a waitlist before the pandemic, but this past spring, their waitlist stretched 80 families long — more than 200 people waiting to join support groups.

“There was such an increase in death by overdose, death by suicide,” Duke said. “There was even an increase in death by car accidents, let alone death by Covid.”

Bridges is also a free program in a time when many families are struggling financially.

The social workers there not only organize evening support groups; they also help connect families to food banks, programs that can help with rent or utilities payments, or help getting into individual counseling.

Duke said she’s worked to get people off the waitlist by adding groups and by asking families to stay in the program only about a year.

“Before the pandemic, families were allowed to stay in the support groups as long as it was helpful to them,” she said. Families would stay an average of a year, but “some families would stay three-plus years, particularly if it was a very difficult death.”

Christy Maricle and Caileigh are now nearing the end of their time with Bridges. Maricle said that’s okay; they’re doing okay.

“It does get better over time,” she said. “As much as you don’t believe it in the beginning, it does.”

Back at the Bridges group in late November, kids were at different stages with their grief. In a closing exercise, they lit candles and said their missing loved one’s name.

“My mommy died,” one said.

“My dad died,” said another.

“My mom and dog,” a 5-year-old said.

For one boy who’d been quiet the whole evening, it was still too raw. When it was his turn, he declined to speak.

His sister said the name for him: “Our mom,” she said.

Listen to Part 2 of the audio story below.

News 20221222 Me Lostcaregiverspt2 Fea Eo

For a child, the death of a parent can be tough to grasp or to find the words to talk about it. Across Washington, more than fourteen hundred kids have lost a caregiver to Covid. And programs that help families navigate this loss are struggling to find space for everyone who needs it. KUOW’s Eilís O’Neill has our story about a program in Tacoma seeing record demand for their services.