Language is often weaponized against trans people. Does the word 'transphobic' capture this moment?

The Washington Legislature has passed a bill protecting young transgender people from the reach of anti-trans health care laws in other states. Kentucky, Florida, and Texas are some of the states that have banned gender-affirming health care for minors. Other states have passed laws about bathrooms students can use, sports teams they can join, and how they can discuss gender and sexuality.

These sentiments are commonly described as “transphobic.” Some people use transphobic to describe both a culture, and individual people. One of them is Jaelynn Scott, a black transgender woman who leads Seattle’s Lavender Rights Project. The group advocates for Black and Indigenous gender-diverse people.

Scott says she has no problem saying that individual people are phobic about her, for overlapping reasons.

“You have the fear that goes along with the power of Black women and their association of anger with us,” she says. “You have Black identity in general and the guilt associated with the experience of Black people in this country, from people who are not Black. Then you have trans identity. The wish to erase us as a people is deeply rooted in fear. We threaten everything they have understood to exist, about identity and gender identity.”

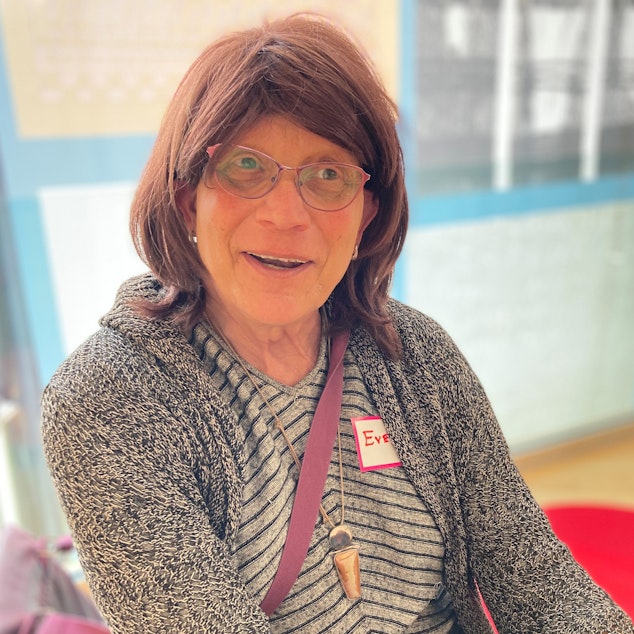

Eve Palay feels differently about the word “transphobic." Palay is a white transgender woman on Bainbridge Island. She’s a dispute resolution mediator and a trans advocate.

“I’m not comfortable with the word ‘transphobic’ because I don't know anybody who's been afraid of me,” Palay says. “I haven't had that experience on Bainbridge Island, Sequim, Port Angeles, Port Townsend, or Wenatchee.”

Palay says she uses “transphobic” to describe our culture, but not to describe an individual person.

“I'm not in the mind of these people,” Palay says. “I think very often, they’re reacting to something unknown, something changing. They want some certainties in their life and these certainties are very valuable to them. If I accuse somebody of being transphobic, that will put them into a defensive position, and I won't be able to help them, they won't be able to help me. Connection is one of the most fundamental human needs. The way to have connection is to build trust. Language, ideally, is a way to build trust.”

Scott says she agrees with Palay that an interpersonal approach to language helps when building relationships. But she adds, “Black people have always found power in naming truth and naming social problems versus the interpersonal.”

“I think a lot of our community is in shock, anger, disbelief, that words that are being used in the mainstream, in the halls of Congress, in the Kentucky Legislature, even in our Washington state Legislature — “groomer,” wrong identities for who we are — words are being used as weapons against us,” Scott says. “The words that people are using about trans people are making the environment very dangerous for our existence. And it will, if it has not already, cost lives.”

Sponsored

Another place Scott and Palay agree is on the power of positive words. Palay remembers going to a transgender group meeting where the participants had trouble thinking of positive words that describe transgender peoples’ lives. Their immediate word associations included “misgendered,” “invisible,” “victims,” and “suicidal.”

Once someone at the meeting suggested the word “fabulous,” more ideas flowed. People called out “enlightened, unafraid, caring, protective, strong, stable, authentic, and joy,” Palay says.

Scott says Palay’s story resonates with her.

“There are no truer words to my heart, especially at this moment,” she says. But she’s careful not to silence the negative words.

“Black folks hold paradox really well," Scott explains. "We're able to be getting ready for a protest where some of us might be harmed and possibly killed. But in the midst of that, we're eating dinner and laughing together and creating radical songs of worship. We have to hold these two things together or lose the awareness of oppression and danger. But we can't exist just in that. We have to also exist in our birthright, which is the joy of being trans, the joy of being Black and trans, the joy of being Black, and all of those things that we are.”