King County has 'fat stacks' of rent relief for landlords. But some aren't interested

The pandemic has put lots of renters in precarious positions. There’s relief money available, and King County is working through the backlog, sending checks to landlords to help keep financially-stressed tenants housed.

And now agents have run up against new problem: Landlords that don’t respond.

Caseworkers say these landlords are slowing down the system. Landlords say it's about lack of trust.

Melinda Salvana is a couple months behind on her rent. She has been homeless before, and she really wants to avoid an eviction.

“I don’t want [my daughter] to experience a homeless situation. Because it’s hard. Even me, in my situation, it’s so hard. But for the sake of my daughter...”

Salvana's daughter is 10.

RELATED: In King County, rent relief is flowing but funds are drying up

Sponsored

Like 34,000 people in King County, she applied for rent relief. An agency called Open Doors for Multicultural Families handled her case.

A caseworker gave her the good news: The government would pay her bill.

Salvana was overjoyed. But then, when she got home, she saw something surprising: A notice to pay or vacate the apartment was taped to her door.

“When I received again the notice from the landlord, I was surprised," she said. "I thought it had been paid, that it had been resolved.”

But there was a problem. The landlord was not responding to the agency’s offer of payment. KUOW also reached out to the landlord, but received no response.

Sponsored

A small problem having a big impact

Diana Atanacio is a manager at Open Doors. She’s the case manager for this renter.

It’s frustrating, she said, that if a landlord won’t accept the money, there’s not a lot her agency can do.

She told the story of what happened to a different client.

“We had one landlord, she was refusing, to the point that she emailed me, capitalized, bolded, blue, making it clear – I am not signing the agreement. At that moment, I was furious. I was like, we are trying to help you. We are trying to help our client.”

Sponsored

Eventually, that landlord gave in.

“But it took us more than a month of struggles. Of her going back and forth, back and forth,” Atanacio said.

Governments at all levels have been trying to make rent relief programs easier for landlords and renters. The federal government cut down on the paperwork requirements and King County streamlined its own process dramatically. But some landlords still aren’t interested.

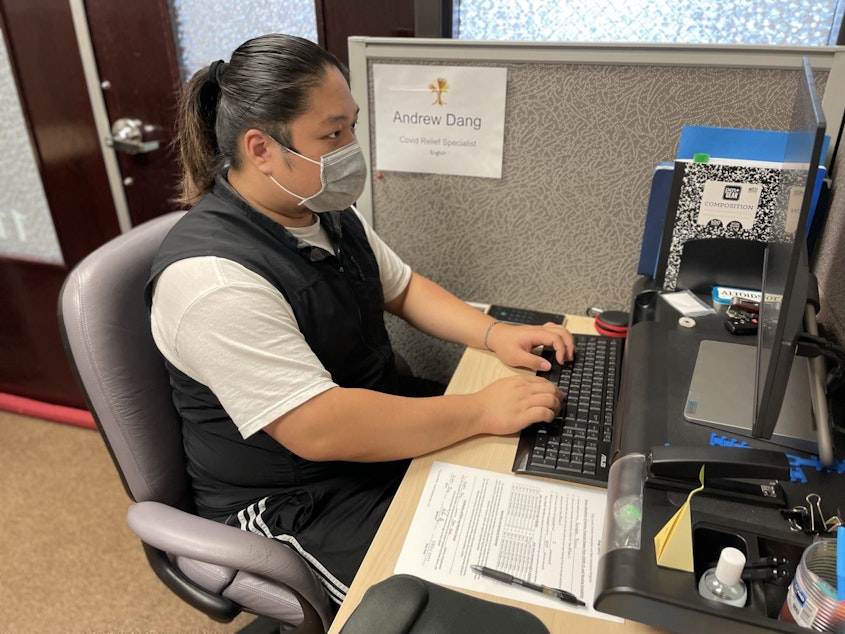

When Atanacio hits a brick wall, she sends in Andrew Dang. You could call him her “closer.”

Sponsored

He shows up at an apartment complex and asks people where the landlord’s office is. As he approaches the door, he mentally prepares himself.

“I’m rehearsing my lines in his head. And just like, what do I have to say to convince them that this is a good thing? Which, frankly, it is. There are not a lot of downsides.”

Dang offers to pay the landlord nine months of back rent and three months of future rent.

“You get a fat stack of cash," he tells them. "You have to pay the tax for it, sure, but the benefit so outweighs that small tax amount ... Just take it. The tenant needs it, you want that money, it’s not a bad thing.”

After he’s made his argument in person, Dang has had only one landlord refuse that offer. So the method is effective, but time consuming.

Sponsored

Reluctant landlords make up only 5-6% of the cases at this particular agency. But Atanacio says they take up a far greater percentage of the staff’s time.

Housing providers respond

Jim Henderson is a lobbyist with Washington’s Rental Housing Association. He says there are lots of reasons for landlords to turn down those stacks of cash. When landlords take the money, they sign away certain rights. For example, they agree not to raise the rent for six months.

“Housing providers have gone almost two years without rent increases on property," he said. "And expenses have dramatically increased, and the cost of operating the property has dramatically increased. And in order to be successful in this business, in order to provide quality housing, you need to be able to cover the cost of that housing.”

Henderson has other complaints, too, about these agreements. But bottom line, he said there’s a trust issue here. He said the program’s administrators at King County, and its many agents, have not earned the trust of landlords.

Henderson said housing providers are seldom consulted about programs like this.

“If they believed that housing providers are necessary and important in the community, then they would be treated and regarded differently and they would stick up for those housing providers.”

King County's backup plan

Whether landlords take these rent relief offers or not may not matter in the end.

Hedda McLendon directs King County's Covid Emergency Services Group. She works on rent relief programs.

“We do want to negotiate and really get the landlords to a "yes" when it comes to rental assistance,” she said.

But when the landlord refuses, the county has other tools.

“We have put in place our stopgap. If for some reason the landlord says 'no,' and tries to start the eviction process,” then lawyers with the King County Housing Justice Project can try to block the eviction in court.

Things didn’t get that far, in the case of Melinda Salvana, the renter at the beginning of this story, who’s afraid of becoming homeless with her 10-year-old daughter. The landlord gave in, Diana Atanacio told KUOW in an email before this story published. Salvana may remain in her apartment.

And that’s how King County prefers things to work. Going to court is more expensive and is considered a last resort. And the county’s working with a pool of money that won’t last forever.

RELATED: In King County, rent relief is flowing but funds are drying up