King County aims to slash carbon emissions in half by 2030, including aviation

The King County Council unanimously approved a new climate strategy Tuesday, aimed at cutting the county's climate-harming pollution in half in less than a decade.

In addition to halving the climate impact of Washington’s most populous county by 2030, the strategy aims to cut countywide emissions 80% by 2050.

The measure also sets a steeper goal for county government operations, including the King County International Airport, better known as Boeing Field: cut emissions 80% by 2030.

“These are big lifts,” said Rod Dembowski, a King County councilmember. “They are going to be very challenging to achieve. I don’t think we should shy away from acknowledging that.”

The plan, shaped by input from community groups concerned about the disproportionate impacts of pollution on people of color, aims to put the needs of vulnerable communities first as the region weans itself from fossil fuels and prepares for a hotter climate.

Many governments and businesses have set voluntary targets like these — and have often failed to meet them.

Sponsored

King County announced a goal in 2008 to reduce carbon pollution 25% by 2020. Instead, emissions in the county fell just 1.2% from 2007 to 2017, according to the county's most recently available data.

County officials say their new targets are backed by specific measures to revamp transportation, buildings, and other big pollution sources. Those measures include boosting transit use, increasing density and adopting a per-mile “carbon fee” for drivers.

The climate plan did not address the growing problem of aviation emissions when County Executive Dow Constantine proposed it in August. But activists succeeded in pushing the county council to ultimately include aviation.

Maria Batayola with El Centro de la Raza said community groups are concerned about the impacts of jet exhaust on the global climate and on the health of people living near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in south King County.

“When you look at the communities out around the airport, we’re talking a quarter million people that’s impacted,” Batayola said.

Sponsored

Hidden toll

Climate activists contend that governments are badly undercounting the global toll of aviation.

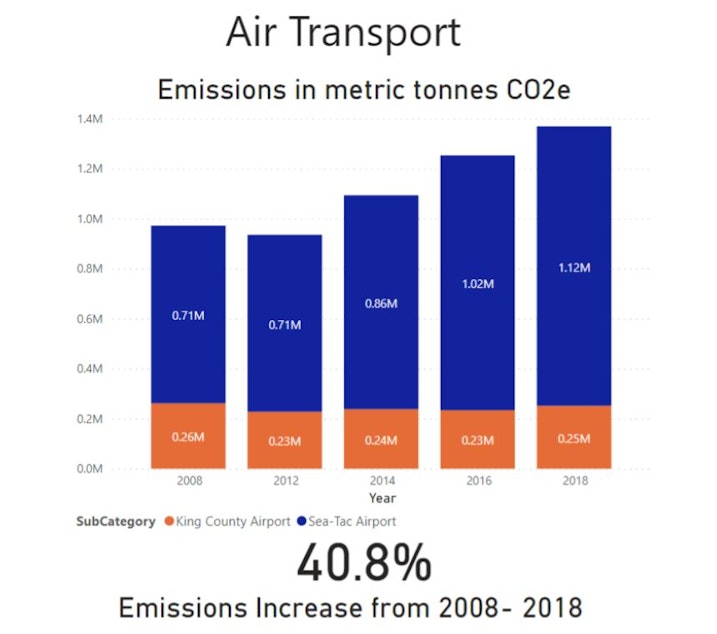

According to a 2019 county inventory, aviation is responsible for 3.6% of King County’s climate impact — far less than motor vehicles, homes, businesses, or industry.

That estimate depends on the inventory’s highly selective carbon math: to approximate the jet fuel burned locally during takeoffs and landings, the report only considers 10% of the fuel pumped at King County and Seattle-Tacoma International airports. The other 90% is off the books.

Counting all the jet fuel pumped at the two big airports, the aviation sector’s heat-trapping emissions skyrocket to 27% of the county’s total, surpassing the impact of cars and trucks.

Sponsored

King County's new plan promises to comprehensively track aviation’s carbon emissions and sets up a community task force to recommend options for reducing them.

“This is an exceptional, historic moment for aircraft emissions that were not included to be included in the greenhouse gas inventory,” Batayola said. “We cannot look for a net reduction in greenhouse gases if we don't do an accurate accounting of what's being emitted.”

Local governments’ options for regulating pollution from airplanes are constrained by federal law.

“They're legally preempted from setting a lot of those emission standards on the state or city level,” said Sola Zheng with the International Council for Clean Transportation in San Francisco. “We think the opportunities are mostly on the fuels and airports side, where the local governments have more authority.”

“Aviation and maritime fuels/emissions are federally regulated under the commerce clause [of the U.S. Constitution], so states can only provide incentives,” Washington state Sen. Reuven Carlyle said in a text message.

Sponsored

In January, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under the outgoing Trump administration finalized the nation’s first-ever regulations of greenhouse gas emissions from airplanes.

The new standards were so lax that the agency predicted they would have no effect, and the Biden administration is now reviewing them.

Washington state transportation officials predict that the demand for passenger flights and air cargo will double in the next twenty years. The state is planning to expand various airports and build a brand-new one to handle that demand.

Sponsored

King County is planning to expand its Boeing Field airport.

“The fact that the county on one hand espouses a commitment to climate, and on the other hand may approve a plan that will significantly increase climate pollution, is deeply frustrating to say the least,” said Sarah Shifley, a climate activist with 350 Seattle, in an email.

County spokesperson Cameron Satterfield said flights at Boeing Field have decreased by half since 2005 and the “modest increase” foreseen by planners would yield flight volumes well below those of 15 years ago.

Boeing Field officials expect small-plane flights to keep decreasing, while cargo, charter, and corporate jet traffic will grow 10% to 30%.

Des Moines City Councilmember JC Harris urged the King County Council to work with other local governments to reduce the demand for air travel.

“Only about 15% of air travel is for tourism or to visit grandma,” Harris said. “We have all learned to do a great deal of work remotely now, and the county can continue doing as much as possible remotely and continue to not take unnecessary air travel.”

A rare commodity

“We share the county’s ambition,” said Steven Levesque with Leading Edge Jet Center, which sells jet fuel and, since December, bio-jet fuel at Boeing Field. “We’re continually searching for ways to reduce our carbon footprint.”

Also known as sustainable aviation fuel, bio-jet fuel is made from crops or waste products, not petroleum. Manufacturers claim it has up to 80% less climate impact than petroleum fuel, depending how it’s made and what raw materials go into it.

While batteries remain too heavy to power all but the shortest flights, the aviation industry is pinning its hopes on biofuels as a strategy to tame the global impact of flight — and forestall more drastic regulation.

On Wednesday, France banned airport expansions, construction of new airports, and most domestic flights on routes served by train trips of two and a half hours or less.

In December, King County announced delivery of the first shipment of 7,300 gallons of bio-jet fuel to Boeing Field — less than it takes to fuel up one of the big cargo planes that regularly land there.

Levesque declined, “for competitive reasons,” to say how much bio-jet fuel Leading Edge has dispensed at Boeing Field since December.

Biofuel for jets is currently a rare and precious commodity, with a much greater presence in aviation advertising and press releases than actual fuel tanks.

It now costs about $6 a gallon, three times the price of ordinary jet fuel, according to Stephanie Meyn with Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

Fuel pumps at Boeing Field dispense about 26 million gallons of petroleum jet fuel annually. Sea-Tac airport pumps out about 600 million gallons a year.

Current world production of bio-jet fuel, according to Meyn, is just 5 million gallons a year.

“That remains a challenge,” she said. “The good news is capacity is increasing steadily.”

Meyn said Washington state’s new low-carbon fuel standard law should help boost supplies, though jet owners have to compete with truckers and other diesel engine owners for the limited resource.

There’s only one bio-jet fuel facility in the United States, Meyn said, with two under construction.

In Lakeview, Oregon, Red Rock Biofuels plans to open a plant in 2022 to convert wood waste from forestry operations into 16 million gallons of diesel and jet fuel annually.

Over the coming decade, King County’s new climate goals are less ambitious than Seattle’s Green New Deal, which sets out to eliminate climate pollution by 2030 — and nearly as ambitious as Washington state’s 2030 mandate.

In the long term, the county aspires to less carbon reduction — 80% by 2050 — than Washington state’s mandate to reduce emissions 95% statewide by 2050.

“This is exciting,” said King County Councilmember Kathy Lambert before voting for the new climate strategy. “I hope that our children and grandchildren are some day very pleased with what we brought forth.”