How one transgender dancer challenges the Bollywood binary

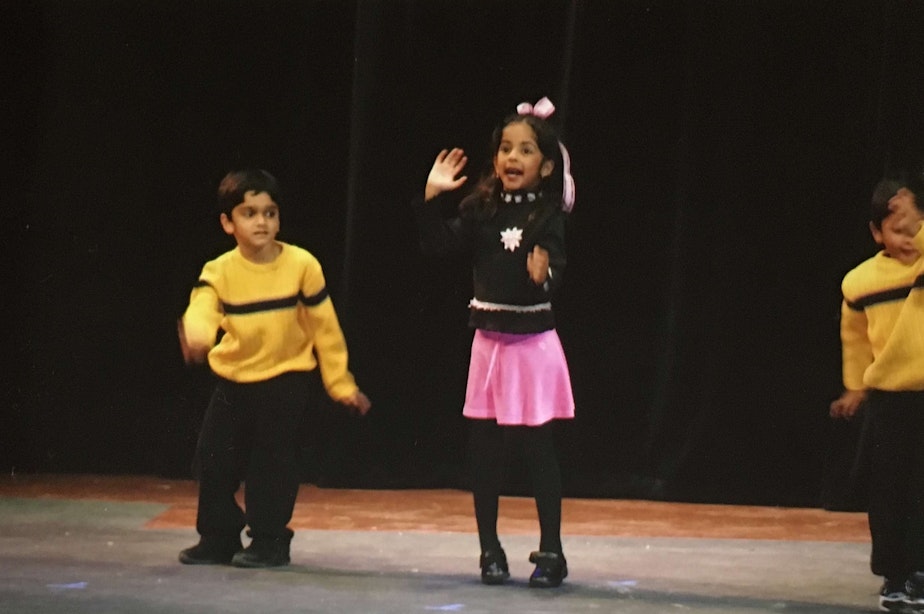

1 of 2Evon Mahesh dreams of teaching Bollywood dance to kids in a way that focuses on rhythm and movement, not gender.

1 of 2Evon Mahesh dreams of teaching Bollywood dance to kids in a way that focuses on rhythm and movement, not gender.Everyone longs to be their truest self. But what if being your true self means you have to give up the thing you love most?

I'm dancing with my friend, Evon Mahesh, in his garage.

A lot of Indian kids grow up dancing in garages, where someone's parent teaches all the kids a dance for the next puja, or Indian cultural event.

This was Evon's life from age 5 to 15, dancing every day and loving every second of it.

"When I'm dancing," he told me, "I feel like I'm really in my own world. Like nobody else is there."

Plus, Bollywood dance was the way that he connected to his Indian community.

Bollywood is so upbeat and fun, but it's also super gendered. The girls are sexy, the guys are tough, and there are no other options.

Evon tells me that in every dance, there's the leading girl and the leading guy. "The girl has very specific steps, and the guy has very specific steps, and there's nothing really in between.

"I always felt like I was somewhere in between."

Evon is transgender. He was assigned female at birth, and then transitioned to male.

This didn't fit within the norms of Bollywood. There was no space for his gender identity, and it became difficult to transition while continuing to dance.

He wasn't comfortable doing the hyper-feminine dance movies in his dance classes, and his dance community didn't use the name and pronouns he asked them to use. Instead, they used female pronouns and the name he was assigned at birth.

"I would hear this name," he said, "That I so deeply detest, and I would flinch."

He began to hate every part of dance, even the parts he used to love: the sounds of bells tied around ankles, the swishing of the lehengas, the sequins hitting each other on the cheap costume fabric.

"I hated those songs," he said.

At the same time, he was trying to decide whether to medically transition and begin taking testosterone.

On the one hand, he knew it would make him feel so much better in his body. But on the other hand, he knew he couldn't show up to his recital with facial hair and a low voice, and then put on the same skirts and bangles.

He had to make the choice to either be in the body that he wanted, or keep dancing.

He knew what he had to do.

"I quit," he said. "After a lot of tears. I cried every day leading up to it."

Evon gave up dance as a part of his life.

"It always felt like my connection to my community was through dance," he said. "I lost that. I didn't see my dance friends anymore. They were like cousins."

The next two years were rough. He got involved with school clubs and played piano, but nothing made him feel the way dance did: connected, alive, and free.

Then, everything changed.

A South Asian non-profit held a performance event with a Bollywood dance number at the end, and they asked Evon to be part of it.

The choreography and costumes were gender inclusive, neither masculine nor feminine.

"That memory of dancing on stage," he said, "To do this dance I felt confident doing, with these people I felt comfortable around, almost erased all those bad memories I had.

"It became what I remember of dance... having fun, being with my community, feeling good, and feeling the rhythm of the song."

It's a new kind of Bollywood — one that shatters the boxes of masculinity and femininity, and embraces Evon for who he is.

Now, Evon is 17-years-old, and dreams of teaching Bollywood dance to kids in a way that's about rhythm and movement, not gender.

This story was created in KUOW's RadioActive Intro to Journalism Workshop for 15- to 18-year-olds at Jack Straw Cultural Center, with production support from Kyle Norris. Edited by Caroline Chamberlain Gomez.

Find RadioActive on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, and on the RadioActive podcast.