Heavier rainfall to cost Seattle area billions to avoid sewage spills

More-intense storms are expected to cost the Seattle area billions of dollars in coming decades — and that doesn't include the potential for more flooding or landslides.

The extra billions would be needed to build sewage treatment plants big enough to handle heavier runoff as the climate changes.

King County is already in deep doo-doo for not doing enough to keep raw sewage from pouring into local waters after big storms.

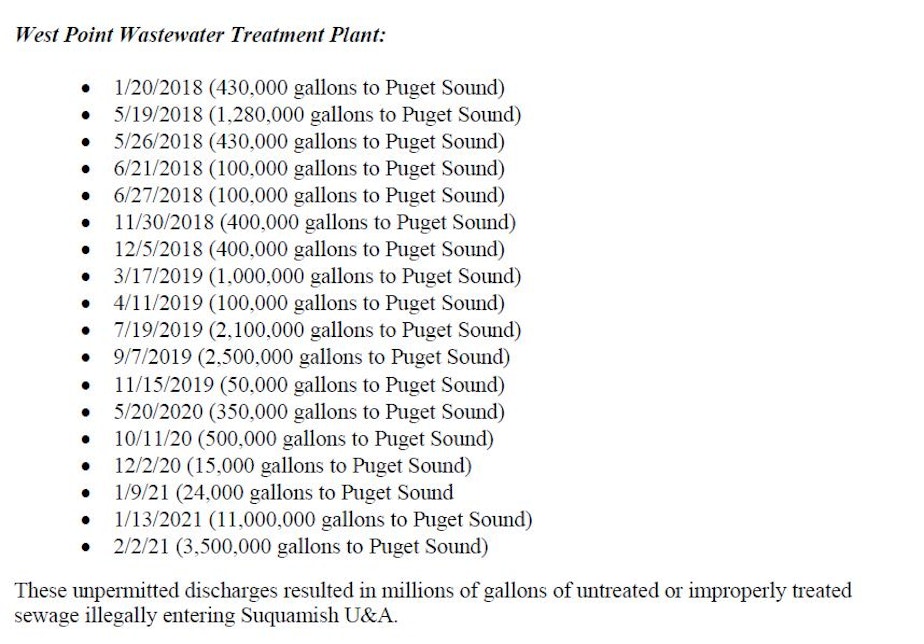

In December, state and federal agencies fined the county and the City of Seattle for “combined sewer overflows,” when heavy rainfall overwhelms sewage treatment plants, and the untreated mix of runoff and sewage is shunted into the environment.

After threatening to sue last summer, lawyers for the Suquamish Tribe have been negotiating with the county to fix its chronic overflow problem.

The Suquamish Reservation on the Kitsap Peninsula sits eight watery miles due west of Seattle. The tribe's traditional fishing areas in Puget Sound extend to the Seattle shoreline.

Sponsored

In March, the tribe again notified the county that it intends to sue over the continued discharges of millions of gallons of raw sewage into the waters the tribe relies on.

Sewage spills from King County sent 11 million gallons into Puget Sound in January and 3.5 million gallons in February.

“The Suquamish Tribe and its members are harmed by the County’s discharges, which foul the water and habitat for aquatic species, result in the posting of health advisories and closure of beaches where Suquamish tribal members harvest shellfish, prompt recalls of commercially sold shellfish, interfere with tribal member harvest and sale of salmon, and disturb important cultural activities such as the annual Canoe Journey,” the tribe’s new complaint states.

Sponsored

Bob Swarner with King County’s Wastewater Treatment Division told a climate conference on Tuesday that fixing the county’s overflow problem could cost $3 billion to $4 billion -- without the climate changing at all.

He said the intensified rainfall expected by climate scientists could drive up by roughly half how big wastewater plants need to be.

“This is a multibillion dollar program that we have now,” Swarner said, “and if we added 44% to 58%, it’s going to be a sizeable cost increase.”

He spoke at the University of Washington’s Northwest Climate Conference, an annual event focused on how the region can best adapt to its rapidly changing climate.

Swarner said King County is already using projections of the region’s hotter, wetter winters to design bigger sewage treatment facilities.

Sponsored

He said the county is responsible for about 37 sites that cause combined sewer overflows, while the city of Seattle has 82 such sites.

King County handles the liquid waste of 1.9 million people with three major treatment plants and 391 miles of pipe.

Swarner said his cost estimate was very preliminary and did not include any costs the city of Seattle might face to make needed upgrades to its sewer systems.

Under a 2013 consent decree with the Department of Justice, Environmental Protection Agency and Washington Department of Ecology, King County is required to have no more than one combined sewer overflow per year at any of its wastewater facilities. The city of Seattle operates its facilities under a separate decree with the same agencies.