Former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice and the origins of Seattle's growth strategy

Seattle is expecting a quarter million new people by 2044. Where will they all live? We haven’t built enough new homes.

The city is updating its plan for where it will build homes in the decades to come. And it’s taking a second look at a strategy that has defined its growth over the last 30 years.

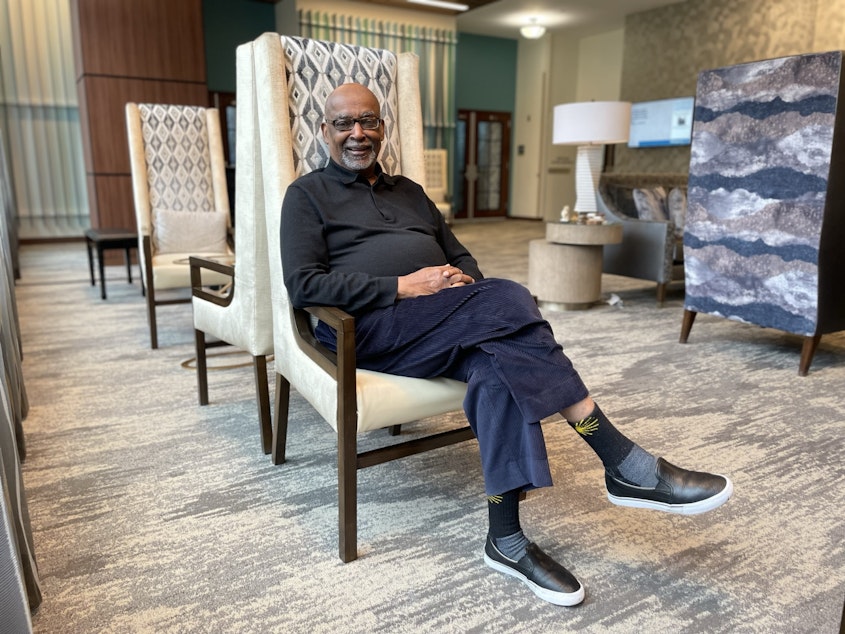

No one is more associated with urban villages than former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice, who championed the concept three decades ago.

The idea is to cluster density in limited areas with good transit service (it was all bus service at the time), build tall buildings in some places, so you can keep other parts of the city more or less as is.

“I really think that when we started out, the car was the bane of everybody’s existence," Rice said while sitting in his high-rise retirement home on First Hill. "We were building things for cars.”

In the '60s, '70s and '80s, Rice says our region built malls and suburban housing developments and freeways — urban sprawl.

Sponsored

In 1990, he was elected mayor and inherited a city damaged by all this car-oriented development.

"We were building things for cars. We were making sure that cars could get to the places were they need to be," Rice explained. "And if you do that, you need parking lots, you need big, open places. That’s a problem."

All over Seattle, people were tearing down historic buildings and replacing them with parking lots.

But then, Washington state passed a law to try and change that, the Growth Management Act, which forced Washington cities to contain their sprawl by growing up instead of out.

As mayor, Rice had to sell this concept to a skeptical Seattle.

Sponsored

"And there are a whole lot of people that looked at density as the worst thing in the world you could ever think of," he said. "You know, you’re gonna destroy my parks. You’re gonna have tall buildings and no sense of community."

Rice asked city residents what they wanted.

"When we have our focus groups, what did people say? 'I would really like to live in a place where maybe I could walk to the store. Or kids could walk to school,'" he recalled. "All the kinds of things that make you stay in the neighborhood. That’s where this concept of the village came from."

Rice is really proud of urban villages, and how they emerged from this community process — lots of meetings and deep listening.

But not everybody was at those meetings.

Sponsored

And 30 years later, that’s led to some big problems in Seattle, related to which communities are bearing the brunt of development and who gets to buy a home.

Now, the city is trying to change that.

Michael Hubner, a long-range planning manager with the city of Seattle, says today, there's a deeper understanding that you can’t just hold meetings and hope people come to you. You’ve got to go to them.

“That’s a real cornerstone of what we’re doing that I think sets it apart from the planning work in the 1990s that really established the urban village strategy,” Hubner explained.

That outreach is just starting, but already, the city has heard from BIPOC families who feel they’re being shut out of opportunities for homeownership.

Sponsored

The vast majority of the city’s growth, 83%, has been in urban villages. But most of what gets built are apartments for rent, not homes you can buy.

There are more reasons to rethink the strategy, according to Hubner.

“It’s not just about home ownership," he said, "It’s also about quality of life, and access to opportunity.”

Hubner pointed out the need to access big city parks, like Discovery Park, which are mostly surrounded by single-family homes.

Sponsored

He said more people need the ability to live in quiet neighborhoods, with less air pollution.

Inside urban villages, high competition for land encourages the market to focus on smaller homes. Outside of urban villages, there's room for townhomes with three and four bedrooms that are large enough for growing families.

“All of those things can be addressed by looking at housing options outside of the villages," Hubner said. "That’s something that we’re exploring different ways of doing that in this comprehensive plan update.”

As Seattle updates its comprehensive plan, it’s looking at ways to revise the urban village strategy.

Rice says he would be OK if that happened.

“Times change," he said. "And no plan, in my mind, is the plan forever.”

The city has a few new options on the table.

It could create more urban villages, maybe smaller ones, or redirect growth to busy roads with lots of transit. Or it could encourage more townhomes in parts of the city that were protected under Rice’s plan three decades ago.

RELATED: Where should Seattle build homes for newcomers?

Whatever happens, Rice warns: Not everyone is going to be happy.

“I think growth management — density, change — is the biggest thing and the hardest thing for everybody," he said. "We came here for a certain reason. Most of us came because we love the place, and we’ve seen it change."

Change is inevitable, Rice said, and it's impossible to go back to the way Seattle was in the '80s or '90s.

"Our first instinct is to try to go back," he said. "But the world has changed. You can’t go back. But we can say, ‘What will we do now?’ And then you go to people and say, ‘Can you help me get to this place?’”

Rice doesn’t know what that future place will look like. But he’s optimistic.

Because rethinking urban villages isn’t about throwing out a bad idea. It’s about celebrating the ways they’ve succeeded and trying to grow access, so that more and more people can enjoy them.

And enjoy other kinds of neighborhoods, too.