Employees say state insurance chief used racist slurs, mistreated staff

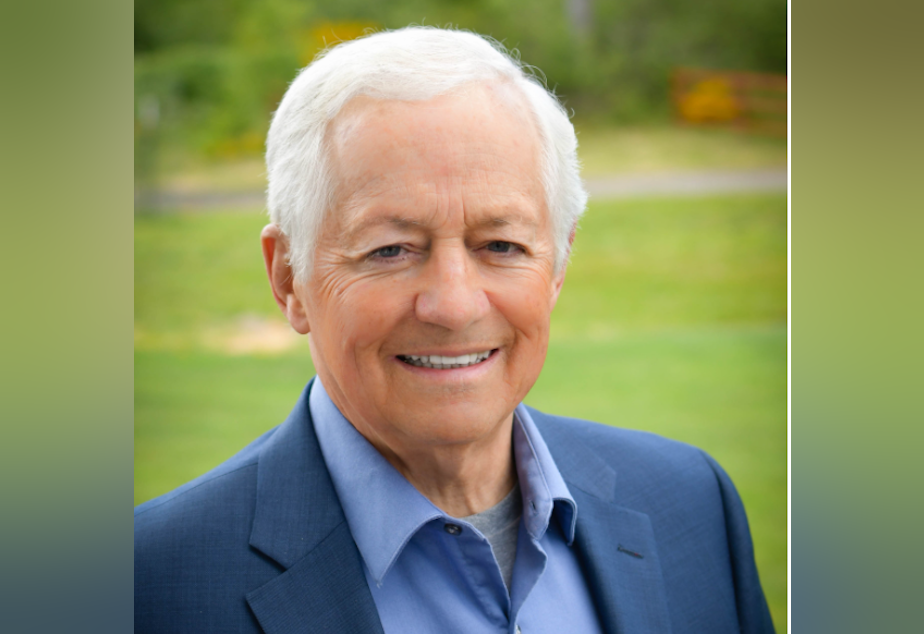

When a finalist for a high-ranking job at the office of the Washington Insurance Commissioner sat down with Mike Kreidler last autumn for an interview, the woman was excited to work for a small agency with a record of advocating for marginalized communities.

But Kreidler, Washington’s longest-serving current statewide elected official, immediately turned the conversation to her race and ethnicity, according to the job finalist, who is Japanese American and was born in Hawaii.

His first question was whether her great-grandparents came over to Hawaii to work on sugar plantations or pineapple plantations, said the job applicant.

Kreidler went on to say he didn’t consider people of Japanese descent a minority or disadvantaged based on his experience going to school with many of them, according to the woman, who spoke on the condition she not be named for fear of damaging her career in state government.

By the end of the interview, she had already decided to withdraw her application.

“At one point I looked around, because I wasn’t sure if I was in one of those hidden camera shows,” said the woman, who currently works in a high-level position at another state agency. “Personally, I was just in shock. It was racist and highly offensive.”

That job finalist is one of half a dozen former or potential employees who disclosed to The Seattle Times and public radio’s Northwest News Network instances of Kreidler being demeaning or rude, overly focused on race and using derogatory terms for transgender people and people of Mexican, Chinese, Italian or Spanish descent, as well as asking some employees of color for unusual favors. The instances are from 2017 to 2022.

Three former employees recounted how Kreidler, 78, used the racial slur “wetback” in a staff meeting when telling a story from decades ago about a friend’s racist reaction to Kreidler’s soon-to-be wife, who is Mexican American. In an interview, Kreidler said he didn’t recall the specific event, but acknowledged that he’s told that story over the years, “and if somebody took offense to it I feel bad about that.”

In another group meeting, Kreidler described a neighborhood in Tacoma as “Dago Hill,” which he said was a common nickname. In other instances, people heard Kreidler describe an old friend as a “Chinaman” and transgender people as “men with tits.”

Their stories reveal a disconnect between Kreidler’s public image as a progressive Democrat and his management style leading the 260-person agency.

A former policy analyst who is from India said Kreidler asked him to help arrange the commissioner’s travel to that country. A former executive assistant who is Korean American said Kreidler repeatedly asked her to help the commissioner communicate with his Korean neighbors. Another former executive assistant claims Kreidler threw travel documents back at her for booking an economy-class airline ticket — rather than a pricier business-class seat — for him to attend a climate change conference in Switzerland.

These stories by people — some of whom didn’t want to be named out of concern for career ramifications — build on a report last month by Northwest News Network that detailed workers saying Kreidler mistreated staff. Some point to the departure of five of Kreidler’s seven top deputies since March 2020, and an employee satisfaction survey showing high levels of dissatisfaction throughout the agency, as signs of dysfunction.

Kreidler said he’s been ahead of his time in pushing to stop discrimination, and that he’s worked through the years to be “politically correct.”

The insurance commissioner also acknowledged that he is often curious about people’s personal histories, such as his conversation with the job finalist.

He conceded to “every once in a while” using outdated or derogatory terminology.

Asked if he had any medical or cognitive conditions that might contribute to him making such remarks, the office in a statement said Kreidler “does not discuss his medical conditions or status with the media.”

Kreidler said he feels bad if he offended people.

“I take a great deal of pride in what we’ve been able to accomplish here, in being able to help on the issues of discrimination and to minimize it in society,” he said. “There’s more that needs to be done to make sure people aren’t being harmed, and the last thing I want is to ever be in a position where anything I say or do overshadows that.”

A former state lawmaker and member of Congress, Kreidler was elected insurance commissioner in 2000. He is the top state regulator of Washington’s insurance industry, which includes approving rates and advocating for consumers and policyholders, with an annual salary of $140,110.

As commissioner, Kreidler has advocated for federal Affordable Care Act and reproductive health care, and founded a national climate-change working group among insurance officials. In Washington, he has pushed to make sure insurance companies cover medically necessary gender-affirming treatments and has worked to safeguard consumers against surprise health care bills.

And for the past two years, Kreidler has taken on the insurance industry in a quest to ban the use of credit scores to help determine insurance rates, calling it a discriminatory practice that hurts people in marginalized communities.

But for Sandra Murphy, a former executive assistant whom Kreidler asked to speak with his Korean neighbors, the experience led her to try to avoid him in the office.

“It made me feel awkward and uncomfortable and like I had no power,” Murphy said.

“An abuse of power”

Murphy, who is Korean American, recalled how Kreidler walked into her office to ask if Genghis Khan had invaded Korea, and whether she had any Mongol ancestry.

Murphy also said Kreidler more than once asked her to come to his home in Olympia to help communicate with Kreidler’s Korean neighbors over a shared water system.

“I need you to come talk to my neighbors, their accent is so thick … they’re your people, so you could probably communicate better than I could,” recounted Murphy, who said she speaks some Korean. Murphy said she declined several times to help negotiate.

“To me it felt like an abuse of power,” said Murphy, adding later: “It makes me feel mad even to this day.” Murphy ultimately took a pay cut, she said, to leave the office for another job.

Kreidler acknowledged both incidents, but said that he had only asked about the water system in a joking way: “I was being facetious. It was a joke. Obviously, I failed.”

In another instance, one day a few years ago, a couple of staffers gathered with Kreidler to prepare him for an interview that would include a discussion of policy issues involving transgender people.

As staff explained to Kreidler basic terminology, however, one employee recounted that, “He kind of popped off, like, ‘So what are we talking about, men with tits?'”

“I was stunned, that’s not the kind of thing you say,” said the employee, who left the agency earlier this year.

That employee’s supervisor was also in the meeting and confirmed that account, adding that he spoke with Kreidler about it the next day.

Former policy analyst Tabba Alam recounted how in 2019 Kreidler was planning a trip to India. Alam said Kreidler requested his help choosing hotels and answering questions about security while traveling.

“For a couple of days, I had to be constantly on call with my father asking him to reach out to security people, to other people as to how to make [Kreidler’s] stay out there comfortable,” said Alam, whose father lives in India. Alam’s supervisor, who has since left the agency, independently confirmed the incident.

That trip, planned for March 2020, was to be a mix of business and personal time for Kreidler, according to a statement from Kreidler’s office. It ultimately was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The Commissioner’s recollection is that he sought advice from Mr. Alam and that Mr. Alam did not appear to be hesitant or concerned about providing what help he could,” according to the statement.

Another former employee, Bonita Campo, was hired as Kreidler’s executive assistant in December 2018. A few months after that, she recalls, Kreidler was invited to speak at a climate change conference in Switzerland, and Campo arranged his travel.

In Campo’s telling, she booked a regular plane ticket, saying that accounting staff were wary of spending too much money. But when she handed Kreidler the folder with the arrangements, Campo said, he became so upset that it wasn’t a business-class ticket “he threw (the folder) at me and said, ‘I’m not going.'”

“And he said, ‘I’m the commissioner, and I’ll decide how the money is spent,’” Campo said.

“And I just thought to myself, OK, that’s enough,” Campo said. “I walked out, put all the stuff on the desk, picked up my stuff, and I left and I never went back.”

Kreidler said he has no recollection of the incident, saying it “would be out of character for me.”

A dismissed complaint

The policy of the insurance commissioner’s office is to address complaints of harassment on any basis, as well as discrimination or harassment based on protected class status, such as race, sex or age, according to a copy of the document.

The policy — which bears Kreidler’s signature — defines harassing conduct as including “epithets, slurs or negative stereotyping; threatening, intimidating, or hostile acts; denigrating jokes,” and requires all allegations to be investigated.

While none of the former employees filed a formal complaint against Kreidler, Jon Noski, the agency’s legislative affairs director, did in February. He alleged that Kreidler bullied him on Feb. 1, when the commissioner berated Noski after his testimony in a legislative committee on a bill involving credit scoring.

“The commissioner said that I am an impotent embarrassment who might need to be replaced because of my incompetence,” wrote Noski, who as a white man is not in a protected class. “The commissioner said I must enjoy getting pissed on and asked if he needed to wipe my ass.”

Noski, 41, said human resources never reached out to him to gather more information or conduct an interview.

"There’s been no investigating, there’s been no follow-up,” he said. His complaint was first reported by Northwest News Network.

- Instead, a week after it was filed, Michael Wood, who had been recently promoted to be Kreidler’s chief deputy, sent a memo to the agency’s human resources director dismissing the complaint.

In the memo, Wood wrote he discussed the complaint with that director and another high-ranking official, and found no violations of a state law dealing with an “improper governmental action,” such as a waste of government funds or creating a danger to public health and safety.

Wood also wrote that the allegations involved “violations only of policy,” which “are established under the authority of the Commissioner.”

“As such, there is no basis to consider action against him [Kreidler] as the subject of the complaint,” he wrote.

Trish Murphy, a Seattle-based employment attorney who has conducted more than 250 workplace investigations, said employers are “obligated to provide a workplace that does not condone any sort of discriminatory treatment, discriminatory harassment or discriminatory decisions.”

“In my years of experience, I don’t recall ever hearing of an organization or leader taking the position that the leader can’t be held accountable for complying with the organization’s policy,” said Murphy, adding that she couldn’t comment on specific incidents involving Kreidler.

The Insurance Commissioner’s office doesn’t track whether Kreidler complies with a requirement that employees annually acknowledge its anti-harassment and nondiscrimination policy, according to the agency.

While Kreidler recalls taking diversity training at some point, according to his office, the agency has no recent records that show he’s taken such training.

That stands in contrast to all eight of Kreidler’s peers in statewide elected office.

Gov. Jay Inslee, Lt. Gov. Denny Heck, Schools Superintendent Chris Reykdal, Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz, Secretary of State Steve Hobbs, Auditor Pat McCarthy, Treasurer Mike Pellicciotti and Attorney General Bob Ferguson have all taken recent diversity or respectful workplace training, according to their spokespeople.

This story was produced in conjunction with Northwest News Network, a collaboration of public radio stations in Washington and Oregon.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the length of time Mike Kreidler has spent holding elected office.