Electric ferries are cleaner and quieter. For orcas, that might not be enough

Gov. Jay Inslee wants Washington state ferries to switch to electricity.

The governor wants the state legislature to pay for two new electric ferries this year and to convert two others.

Inslee said the cleaner, quieter boats would help the climate and the region’s endangered orcas.

While electric boats emit less air pollution than diesel ferries do, it’s unclear how much good four battery-powered boats serving Seattle-area commuter runs would do for the noise-sensitive whales.

Most underwater noise generated by ships, including the 23 state ferries, comes from their spinning propellers, not their rumbling engines.

Food, water and quiet

Biologists say lack of salmon, clean water and quiet are pushing southern resident killer whales close to extinction.

Ship noise hinders whales from communicating with each other. It also interferes with their echolocation — the sounds orcas bounce off salmon and other prey to home in on them in the murky depths.

Ship noise can travel, and have impacts, many miles underwater.

Sponsored

Inslee is proposing to spend $117 million on electric ferries:

- $64 million to build two new ferries, similar in design to the state’s current fleet, but powered by lithium-ion batteries rather than diesel fuel

- $53 million to convert two of the state’s biggest and dirtiest ferries (the Tacoma and the Wenatchee) to electric power

All four boats would still have diesel power for emergencies.

Under Inslee’s proposal, the converted ferries would continue serving the busy route between downtown Seattle and Bainbridge Island. The two new ferries would run between Mukilteo and Clinton on Whidbey Island.

Ferries in the San Juan Islands, where orcas swim more often than anywhere else Washington ferries sail, would keep clattering along on diesel.

“Switching to greener propulsion systems is a good thing,” biologist Rob Williams with the nonprofit Oceans Initiative said. “You might want to start with the route to San Juan Island, of course.”

On the Bainbridge run, each retrofitted ferry would use up about a third of its battery power on the 30-minute crossing, according to Kevin Bartoy with Washington State Ferries. It could plug in and recharge in port, while passengers are loading, in as little as 20 minutes.

Longer runs could present more logistical difficulties and the risk of shortening the expensive batteries’ life spans if they are drained too deeply, Bartoy said.

The run from Friday Harbor to Canada, across the orcas’ prime salmon-hunting grounds in Haro Strait, takes two hours, beyond the current reach of an all-battery ferry trip.

“Battery technology is growing by leaps and bounds,” Bartoy said. “This project probably wouldn’t have been possible 10 years ago.”

Distinctive rattle

Oceanographer and noise specialist Scott Veirs said Washington state ferries make a distinctive rattle underwater. “They have propellers and rudders at both ends, and most ships don't,” he said.

He shared a recording, from the Orcasound network of hydrophones (underwater microphones), of the ferry Elwha off San Juan Island.

A Washington state ferry crosses Haro Strait

Orcasound.net's October 2017 underwater recording, from 6 miles away, of the ferry Elwha as it crosses the U.S.-Canada border--and critical orca habitat. The noise diminishes as the ferry passes behind a small island west of San Juan Island.

“Honestly it sounds a little bit old, like it's clattering along as it makes its way to and from Canada,” Veirs said.

Electric ferries would be quieter than today’s diesel boats, Veirs said, but probably not in the way orcas need most.

“Retrofitting the engine may reduce the low frequency noise. Killer whales are high frequency specialists, so reducing the low frequency noise for them isn't very important,” Veirs said.

Biologist Williams said a quieter sea might help orcas indirectly — by helping their prey — though there’s been less research done on salmon than on whales.

“We’re finding that juvenile salmon and herring respond to noise much as they do to an approaching predator,” he said. “They school up and try to swim away.”

Washington State Ferries and Canada’s Port of Vancouver have also experimented with slowing ships to reduce the noise orcas must endure. “Slowing down vessels generally does make them quieter,” Bartoy said.

Last summer, ferry captains briefly slowed to 12 knots from 16 knots each time they crossed the two-mile-wide shipping lanes of Haro Strait off San Juan Island.

A strategy to slow down in key locations, or when orcas are within hearing range, could produce benefits at much less cost than replacing entire fleets.

But slowdowns have tradeoffs, too: A slower boat will spend more time making noise before reaching its destination or disappearing around a bend. Orcas could have less quiet time.

“If it turns out that the hardest thing a killer whale has to do, acoustically, is hear the faint echo of its own click off of the swim bladder of a salmon that's half a football field away from it, invisible in Puget Sound,” Veirs said, “then it may be really important to have some quiet periods when you can hear those echoes and decide that you're going to dive down into the murky water.”

Sponsored

The state is launching a noise study, to be carried out this summer, of its entire 23-ferry fleet.

“We need to know how loud we are, particularly in the frequencies that are of concern,” Bartoy said.

The state hopes to have that new, noisy data by fall.

Inslee announced his ferry proposal twice in December: once as part of a $268 million plan aimed at reducing the state’s carbon dioxide emissions and, three days later, as part of a $1.07 billion package of measures aimed at protecting orcas and the salmon they rely on.

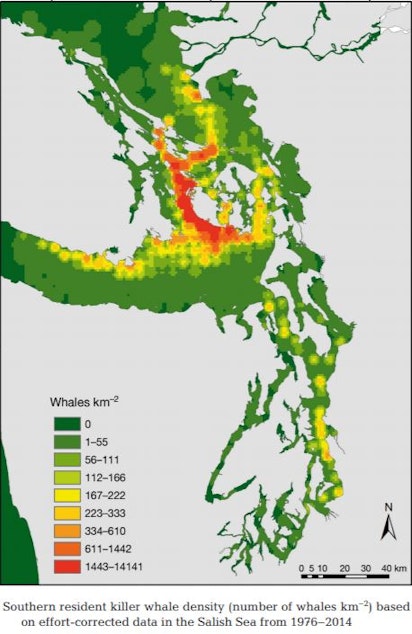

A heat map of where southern resident orcas have spent the most time in the Salish Sea over the past four decades: