Decades later, this photo collection is filling in the corners of Washington's Latino history

In the 1990s, when Washington State University purchased a collection of photographs from Seattle commercial photographer Irwin Nash, they had a general idea of the significance of the material.

Today, that same collection is bringing a vital history to the forefront and showing the significance of how our archives work.

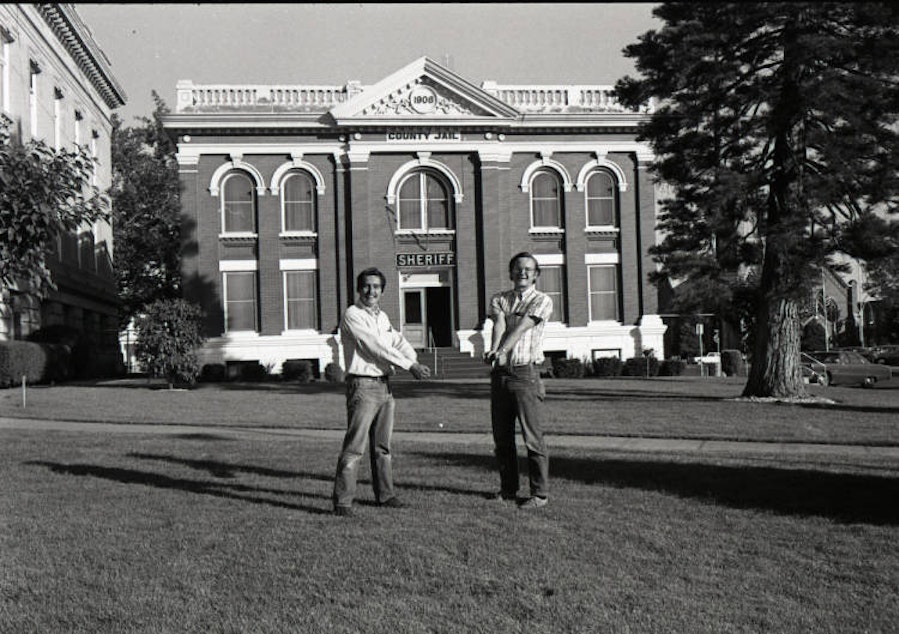

A photographer stands at the edge of a dusty field. He squints through the viewfinder of his camera, which is focused on two men clasping hands over a “No Trespassing” sign. These two men, Guadalupe (Lupe) Gamboa and Michael Fox, were arrested the night prior for attempting to alert farm workers of their right to organize for better living and working conditions. Two years after this photo, their case would go all the way to the Washington State Supreme Court, securing the right for organizers to visit labor camps and inform farm workers of their rights to organize.

The man behind the camera, Irwin Nash, was making sure their story would make it past the dusty fields of the Yakima Valley and closed doors of Olympia to the rest of the state. And though he may not have thought of it at the time, Nash was also securing their story for the rest of history.

Like thousands of immigrants, Gamboa and his family lived and worked on the farms populating the Yakima Valley. At the time, thousands of Mexican immigrants were arriving in the United States on the tails of the bracero program, an agreement struck with Mexico to temporarily house and employ men who agreed to live and work on farms in the wake of a World War II labor shortage. But the program wasn’t enough, so entire families like Gamboa's found themselves working in fields along the west coast. Because workers were at the mercy of their employers for both work and housing, life on these farms could be brutal.

"Social security, workers compensation, unemployment compensation, minimum wage, overtime protections, guaranteed rest breaks -- none of those applied to farm workers” said Michael Fox.

By the late 1960s, Fox had just a year of law experience, and Gamboa was a student at the University of Washington. The two of them were looking to make a difference in living and working conditions, and inspiration came to the University of Washington to help direct their causes. Cesar Chavez, fresh off of organizing grape boycotts in California, was looking to organize in Washington. For Fox and Gamboa, the movement kicked off with a wildcat strike on hops farms, where growers were paying female workers as low as $1.25 an hour, with male workers making $1.50.

Sponsored

Their work was successful, but daunting. Their first strike spread to 15 other hop farms -- but along the way, Michael and Lupe were sometimes met with law enforcement, and threats of violence in the form of bats gripped in hands and guns resting on knees.

“We were just very inexperienced,” said Gamboa. “We thought that we had a lot of power, but then the employers just showed us who really had the power.”

Irwin Nash was largely there to capture it all: the living situations, the labor conditions, the protest meetings and even Fox and Gamboa's arrests. Their efforts made critical progress, helping secure raise wages workers, guarantees for better living conditions, and critically, the overarching right for organizers to go into labor camps over the objection of the camp owner.

Sponsored

But this chapter of history rarely gets publicity.

“There’s no mention at all about what happened in the 70s, about the strikes, about the fact that Cesar Chavez tried to organize there. You go to schools and nothing is taught about this. It’s just understood that you don’t talk about these things,” said Gamboa.

That’s changing today, more than 50 years after Nash first catalogued this history in a collection of 10,000 photographs. He sold this collection to Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections (MASC) at Washington State University in the early 1990s, and since that sale, the photographs have made their way out of their climate-controlled basement only a few times.

But last year, thanks to a serendipitous discovery between the archives and community members, the photographs are bringing new attention to this era of Washington history.

Sponsored

Lipi Turner-Rahman, an archivist at MASC, came upon the photographs and noticed they were incomplete. Many had basic descriptions -- ‘girl with hat picking asparagus’ -- but with such a large collection, the history of who and what were depicted was largely absent. To solve this problem, Turner-Rahman devised a technological solution: the collection would need to be digitized, and from there, offered to the generations of people photographed in it. The archives would crowdsource the history, one photo at a time, through resources like Facebook.

As word spread, MASC was able to secure an $8,000 grant -- a dent in the total digitization cost. That’s when Turner-Rahman was connected with Fox and Gamboa, who, along with community members Laura Solis and Mike Fong, helped raise enough money to finish digitizing the full collection in June of this year. Turner-Rahman continues to regularly post a photo to Facebook, asking for assistance in identifying the people in the image.

For the living people and relatives in the photos, the recent popularity collection is a prideful reminder of Washington’s immigrant history. That pride is shared by Irwin Nash, who is in his mid-80s and living in Seattle.

"I'm very pleased that the people I knew in the valley were able to make use of these photographs, to enrich their feeling about familial history," Nash says. "I took the pictures to illustrate what was going on with a portion of the community that was being treated as less than human."

Sponsored

But there's a catch. Nash wishes he had been consulted on the digitization process, and feels that the collection includes too many "rough drafts" of his work -- things like blurry and duplicate shots. The collection also includes a series of photographs that had nothing to do with the Yakima Valley, which he feels should also be excluded.

"You could tell this story quite cogently with 100 or 145 pictures," he said.

Irwin asked to follow up with the the archives with some questions about their curation process: why wasn’t he consulted about singling out the most important photos in the collection; why did they digitize the full series, mistakes and all; and why are they holding onto selections that have nothing to do with farm workers?

“It’s not our purview to curate it in such a way, to have a certain narrative or story. I believe that the voices of the people, as they look at the photographs, as they see themselves, they themselves will create that narrative,” says archivist Lipi Turner-Rahman.

The collection, she says, is about more than those in front of the camera -- it’s also a reflection of the person behind it.

Sponsored

“Now we all have iPhones and so every photograph is a wonderful photograph. Because we’ve gotten rid of all the blurry ones, the red eyes. So everything is perfection” Turner-Rahman says. “...we’re trying to preserve everything as Irwin took it, as a commercial photographer. During that period, not every photograph was perfect. Not every photograph was in focus. And that in itself tells the story.”