From offices to apartments and back: Could transformable buildings help revive downtowns?

All across this region, we have a housing shortage.

On the other hand, downtown Seattle is littered with vacant offices.

This has some people asking: Why don’t we turn underused office buildings into apartments?

There’s a big old office building, 10 stories tall, in downtown Tacoma. For 100 years, it was a furniture store — and a real eyesore.

“The entire building was covered with brown, corrugated metal," said Harrison Laird, a Tacoma-based commercial real estate broker. "So it kind of looked like a can of beans.”

“Was this place kind of famous for that can of beans look in Tacoma?” I asked.

“It was...very noticeable," he said. "Very noticeable.”

Sponsored

Laird said about 20 years ago, the owner ripped off the brown, corrugated siding, put in new electrical systems, and upgraded the windows.

For the next two decades after that, the building held a warren of cubicles full of people working for a health care company called DaVita, which also made dialysis equipment. The workers toiled under banks of fluorescent lights. When they looked up, some of them would see inspirational slogans on the walls, like “Success is a journey, not a destination.”

Recently, that company left, leaving this big, empty hulk of a building behind. It's old, but it has cool things to offer: Twelve-foot ceilings and sweeping views of downtown Tacoma and Mt. Rainier.

But the building is not cool enough to attract a lot of new companies to sign leases for office space.

“The prospect of filling up a building of this size in today’s market is dismal,” Laird said.

Sponsored

To attract a company today, Laird said an office building needs to be shiny and modern.

“One of the big trends we’re seeing is a renewed flight to quality. Employers are working to get their employees back into the office. And as a part of that, they need great office space. So, 'Class A' buildings, buildings that have all sorts of amenities for their employees, buildings that have gyms and locker rooms and bike storage, tenant lounges, retail — those buildings are the ones that are successfully bringing office tenants back.”

This is not one of those buildings.

Laird said the owner could have waited around for years, to try to fill it. To have hope of doing that, it would need to attract every firm even thinking about locating in Tacoma.

That's a tall order.

Sponsored

Instead, Laird said the owner plans to convert it to high-end apartments.

They’ll have high ceilings, and tall windows with views of Mt Rainier and downtown Tacoma.

Laird said this is the fourth office-to-residential conversion planned in downtown Tacoma.

“It is an outsized trend in Tacoma, relative to the nation. We have an office market that has some outdated product, and a very strong multifamily market. And a vibrant downtown core where people want to be, there’s just not that office demand. So it creates a ripe environment for converting office buildings.”

Sponsored

But that kind of conversion only works on relatively skinny buildings.

Most modern office buildings are too wide. They were designed for a sea of cubicles, and modern lighting and air conditioning meant the architects didn't have to care how far you were from a window.

When you try to carve those buildings up into residences, you end up with very dark, skinny, shoebox-like spaces. Either the back portions of each unit are lit by artificial light only, or you make the units shorter, and fill the center of the building with windowless amenity spaces.

Sponsored

Historic office towers often got around this problem by including a lightwell in their design — a hole through the center of the building, letting in light. Over the years, as those buildings have been modernized, many of those holes have been filled in with elevators and stairs.

Here's another problem with converting offices: In Seattle, office space is twice as expensive as it is in Tacoma. So it’s usually cheaper to build a new apartment tower from scratch than to convert an existing office building.

Here's some back of the napkin math:

- $300/GSF ("per Gross Square Foot") to buy an existing office building in Seattle (excluding land costs)

- Plus $300/GSF to convert it to residential

- Versus $500/GSF to build a residential tower of similar scale from scratch

T

hose inherent constraints have inspired some people to think outside the box.

Matthias Olt is an architect in Seattle. I interviewed him in his empty office building, where we had a view of the Seattle skyline.

He has an idea for a new kind of building that he’d like to see in that skyline.

He calls it the “UN-tower.”

The “UN” stands for “use neutral.”

“The concept behind the use neutral tower is that it’s a building that can adapt easily to a number of uses without expensive conversion costs — or times involved to adopt those use changes,” Olt said.

Kind of like the transformers, from movies and toys. When a transformer needs to get somewhere quickly, it takes the form of a car, or a plane. If it needs to wrestle somebody, it transforms into a giant robot.

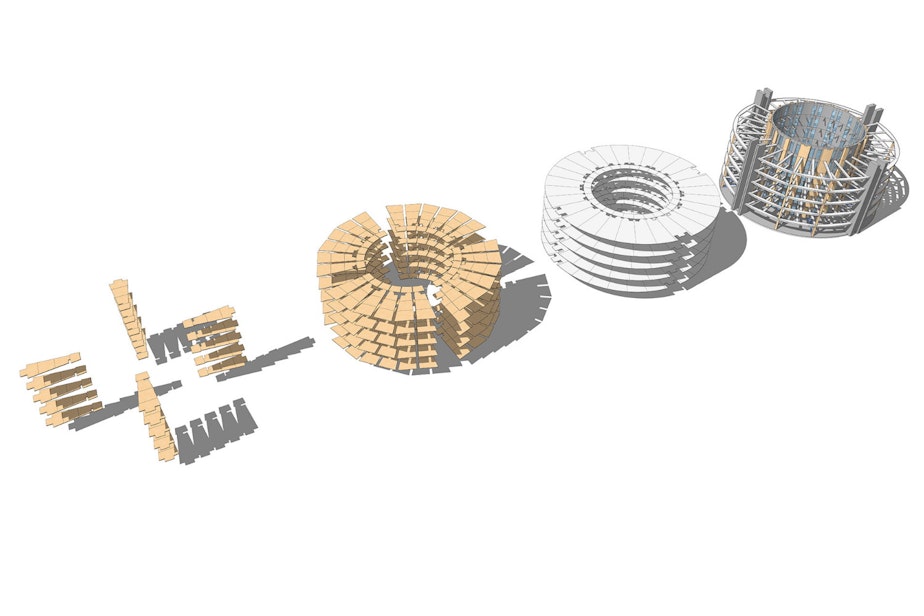

Here’s how it’s organized: Imagine taking a can of pineapple rings; open it up, and take out pineapple slices, and keep stacking those rings until they’re 69 layers high.

Each layer of pineapple is a floor that you can divide up like pieces of a pie into offices, hotel rooms, or apartments.

Because the rings are only 30 feet wide, the occupants of these spaces are never far from a window, for fresh air and sunlight. Every room can have a window.

The way it’s designed makes it easier to reconfigure the spaces inside. The building is like a bunch of Legos that can be taken apart and put together in new ways.

“This form and geometry enable a high degree of repetition of building components and building systems, that ... make the building pencil,” Olt said.

“It feels more like a spaceship, in some ways, than a building — like I see out this window right now,” I said.

“I would concur," Olt said. "And the underlying philosophy of what you call a spaceship — which is not a bad term — is to reposition the way we look at our lives, our values, how we want to live, how we want to work, and how we want to experience our cities.”

Olt is passionate about this project because bringing a lightwell back to a skyscraper reconnects its occupants with nature. Drawings of the building show balconies dripping with plants, and a cathedral-like atrium space at the bottom of the donut hole.

But what developers like is they can start building before they know what the office or housing market will look like when they finish construction, which can take years.

The building can change its use — like a chameleon — from office to apartments to hotels, or whatever is needed in the moment.

Olt said a developer is already considering building a short “UN-tower” in downtown Bellevue. Part of it would be affordable housing.

Office to residential conversions and the UN-tower are two ideas that could make downtowns more resilient. But it turns out, we could think even bigger.

In part three of our series "Downtown Reimagined," we talk to residents and city planners about shaping a new plan for downtown Seattle.